Dr Sally Holloway completed her AHRC-funded PhD on romantic love in eighteenth-century England at Royal Holloway in 2013. She is currently a Historical Researcher at Kensington Palace, and Affiliated Research Scholar at the Centre for the History of the Emotions. In this Valentine’s Day post, she tells the story of a love-lorn Georgian aristocrat….

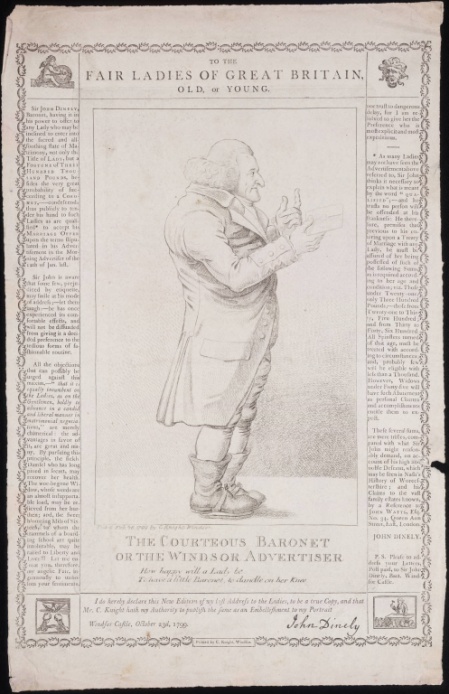

Figure 1 – The Courteous Baronet or The Windsor Advertiser, printed by Charles Knight, 1799, © British Museum.

On 24th February 1799, the ageing baronet Sir John Dineley (1729-1809) of Windsor published an unusual advertisement in the Publicans Morning Advertiser. The advert promoted his quest ‘FOR TENDER LOVE’ as part of his search for a suitable wife. Dineley wrote,

My sweetest Comforters, I trust your Sound Reason will direct you to avoid the false Delicacy that prevents many of you from instantly using your charming Pens, when a Marriage is so safely and profitably offered you, with £300,000; – GLORY IN THIS, and evidently laudable would you be for calling publicly for your Pens to set forth your due GRATITUDE to be adored, commended, and improved in your humane Lines by all around you, – to enable me, or my Attorney to delineate every Mystery in my honourable and sacred Offer that can give you Satisfaction.

SHAME is generally the Sign of Guilt or Ignorance, – By the above Advice you will plainly avoid them both. – Envy or Calumny may deceive you in saying there is no LOVE in the case, but how can you reconcile this Judgment with my Six last Words I advertised in April last, – “In Time to prove your Affection”.

The advertisement noted the many negative emotions which may have been stirred by his curious approach to matrimony, including shame, guilt, ignorance and envy. However, Dineley hoped that certain female readers would be grateful for his promise of love and fortune, and enable him to prove his credentials as a husband. His intriguing proposal was repeated in a pamphlet entitled ‘To the Fair Ladies of Great Britain, Old, or Young’ (Fig. 1), which he distributed among ladies with a ‘most profound bow’.[1] The pamphlet featured his portrait above the rhyme,

‘How happy will a Lady be

To have a little Baronet to dandle on her Knee’.

Dineley also penned a tract entitled Methods to Get Husbands, which could be purchased for one shilling from circulating libraries.[2] He employed all of the tactics in the troubadour’s arsenal, writing ‘A short and elegant song for the ladies’ and repeatedly encouraging women to ‘unbosom your sentiments’ and unleash the ‘feelings of the mind’. A poem anticipated the happy couple’s wedding day, when ‘A beautiful Page shall carefully hold, / Your Ladyship’s Train surrounded with Gold!’

Over the following two years, more than four hundred ladies enquired with Sir John about becoming his wife, with newspapers describing his ‘eccentricities’ as ‘familiar to the public’. Although peculiar, Dineley’s approach was not unheard of – advertisements for love in England and America have recently been analysed in Francesca Beauman’s Shapely Ankle Preferr’d: A History of the Lonely Hearts Ad 1695-2010 (2011) and Pamela Epstein’s ‘Advertising for Love: Matrimonial Advertisements and Public Courtship’. As Epstein notes, men and women printing such adverts ‘expressed the same frustration with the difficulty of meeting a spouse due to restrictive social etiquette as well as isolation in big cities’.[3]

A comparable advertisement can be found from a well-to-do lady advertising for a husband ‘far above the middling class’. The gentlewoman was middle-aged and had been married previously, hoping to find a spouse aged over forty to become a ‘sincere friend, the first treasure in life’. Her advert has been preserved at the Lewis Walpole Library alongside materials relating to Sir John Dineley, and appears to have been published during the same period.[4] If written at a comparable date, it is unfortunate that the two did not meet. However, the proud Sir John would likely have dismissed the lady’s ‘very small’ income, famously tracing his ancestry from ‘the houses of Plantagenet, Lancaster, Tudor, and Stuart’.

Dineley’s own social status had suffered a downward spiral; after inheriting the title of fifth baronet in 1761, he squandered the family money, and was forced to sell their home at Burhope in Herefordshire just nine years later. In 1798 he was saved from destitution and admitted as one of the Poor Knights of Windsor, receiving a pension and accommodation in the grounds of Windsor Castle.[5] His relative poverty did not deter Dineley from his quest for love, parading around leisure venues such as Kensington Gardens, Vauxhall Gardens and Drury Lane dressed in all his finery. Newspapers in 1803 mocked his tehnicolour trappings, describing him as ‘a droll figure, covered with all the colours of the rainbow, and having all the exterior of insanity…He had on scarlet small clothes, a blue waistcoat, and orange coat…as if this dress was not sufficiently attractive, expanded over his head was a large silk umbrella, to protect his delicate countenance from the sun’.[6]

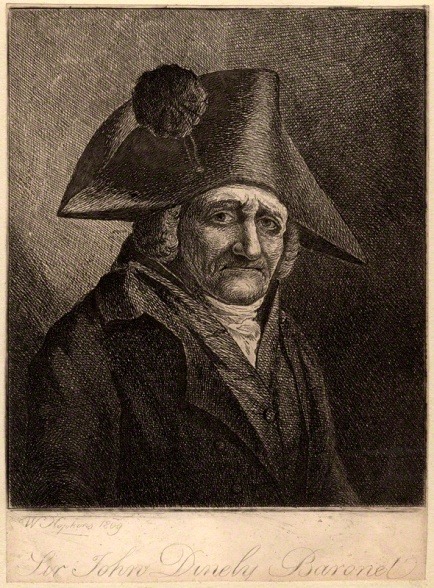

Figure 2 – Sir John Dineley by W. Hopkins, etching, 1809, © National Portrait Gallery.

Unfortunately Dineley’s efforts were ultimately unsuccessful, and the ‘famous amorous Knight’ died a bachelor in 1809.[7] An etching by W. Hopkins the same year depicts Dineley in his powdered wig and bicorn hat, dolefully gazing at the viewer with a furrowed brow. His eccentricities had ‘attracted the attention of a number of people, who followed him wherever he went’.[8] However he never found the companion he yearned for. Perhaps the traditional methods of courtship, whether a love letter, romantic gift, or Valentine’s Card, would have been more effective in helping Dineley to attain wedded bliss. Nonetheless, his actions and how they were perceived by contemporaries provide us with a fascinating insight into the accepted parameters of courtship during the long eighteenth century, and the age, methods, intentions and emotional expectations of those involved.

[1] The Penny Magazine of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (1841), pp. 356-7.

[2] See advertisement in World, London, 15th July 1793, Issue 2042.

[3] Pamela Epstein, ‘Advertising for Love’ in Peter N. Stearns and Susan J. Matt (eds.) Doing Emotions History (2014), pp. 120-142, at 121.

[4] ‘Materials Relating to Sir John Dineley’, LWL MSS Vol. 187, Lewis Walpole Library.

[5] See entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, and post by Eleanor Cracknell on the Windsor Castle Archives blog http://www.stgeorges-windsor.org/archives/blog/?tag=sir-john-dineley

[6] The Bury and Norwich Post: Or, Suffolk, Norfolk, Essex, and Cambridge Advertiser, Bury St Edmunds, 20th April 1803, Issue 1086.

[7] Phrase used in the Bury and Norwich Post, 14th May 1806. His death was also reported three years earlier in The Morning Post and Jackson’s Oxford Journal.

[8] Star, London, 19th June 1798, Issue 3060.