Reviewed for the History of Emotions Blog by Catherine Maxwell, Professor of Victorian Literature in the School of English and Drama, Queen Mary University of London.

Jonathan Reinarz’s Past Scents is a very welcome addition to the burgeoning field of research on the history of the senses and, in particular, the emergent category of olfactory studies. Long classed as a lower ‘animal’ sense as opposed to the higher ‘intellectual’ senses like vision and hearing, smell as a topic of historical study received little serious attention until the 1980s. This changed in 1982 with the publication of Alain Corbin’s massively influential Le Miasme et la jonquille: l’odorat et l’imaginaire social, XVIII-XIXe siècles, a wide-ranging study of the social significance of smell in eighteenth and nineteenth-century France, published in English in

Jonathan Reinarz’s Past Scents is a very welcome addition to the burgeoning field of research on the history of the senses and, in particular, the emergent category of olfactory studies. Long classed as a lower ‘animal’ sense as opposed to the higher ‘intellectual’ senses like vision and hearing, smell as a topic of historical study received little serious attention until the 1980s. This changed in 1982 with the publication of Alain Corbin’s massively influential Le Miasme et la jonquille: l’odorat et l’imaginaire social, XVIII-XIXe siècles, a wide-ranging study of the social significance of smell in eighteenth and nineteenth-century France, published in English in  1986 as The Foul and the Fragrant. In 1994, Aroma: A Cultural History of Smell by Constance Classen, David Howes, and Antony Synott offered the first comprehensive exploration of the cultural role of odours in Western history and examined olfaction in a variety of non-Western cultures. Both these seminal works, along with Patrick Süskind’s best-selling novel Perfume: The Story of a Murder (1986), were crucial in helping arouse interest in the many ways in which smell informs identity and culture.

1986 as The Foul and the Fragrant. In 1994, Aroma: A Cultural History of Smell by Constance Classen, David Howes, and Antony Synott offered the first comprehensive exploration of the cultural role of odours in Western history and examined olfaction in a variety of non-Western cultures. Both these seminal works, along with Patrick Süskind’s best-selling novel Perfume: The Story of a Murder (1986), were crucial in helping arouse interest in the many ways in which smell informs identity and culture.

Since then, and especially during the last decade, work on olfaction has dramatically increased with a current swell of interest in university Literature and History departments. Much of this on-going research – a significant amount being the work of younger academics or PhD students – is as yet unpublished but will likely enrich the field over the next few years. In his Acknowledgements, Reinarz assiduously names other olfactory researchers, some of whom have since brought out work that could not be referenced by him. One example is Victoria Henshaw’s Urban Smellscapes (Routledge, 2014), which regrettably appeared too late to feature in his chapter on smell and the city.

Nonetheless this timely book will be of great interest and a valuable resource to anyone contemplating work on the cultural or historical significance of olfaction or simply wishing to explore the topic further. Reinarz, a medical historian and Director of the History of Medicine Unit at Birmingham University, gives a lucid, well-documented overview of the field, providing serious appraisals of the available scholarly literature. His book opens with a good concise introductory overview of (mainly negative) historical perspectives on smell from classical antiquity onwards, a brief account of how various commentators understood the function of smell and classified odours, and an outline of his own project – six substantial chapters examining religion and smell, the perfume trade, and smell considered in relation to race, gender, class, and the city.

Much of Reinarz’s absorbing study deals with smell as a means of identity and differentiation, marking out one group from another: ‘Christian from the heathen, […] blacks from whites, women from men, virgins from harlots, artisans from aristocracy’ (p. 18). Chapter 1 on ‘sacred scents’ concentrates on ancient Christianity and the increasingly important role of scent in religious practices. Here Reinarz draws on the work of scholars like Susan Harvey to show how ‘smell became a key component in the formulation of Christian knowledge’ and how later ‘Aromatics enveloped every Christian home, shrine, tomb, church, pilgrimage site, and monastic cell and transformed these terrestrial places into ceremonial places’ (p. 27).

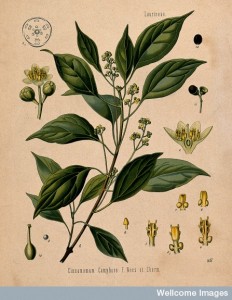

Chapter 2 examines the cultivation and production of perfume ingredients and their global trade from earliest times, along with scent manufacture up to and including the emergence of the modern perfume industry. It features a brief treatment of frankincense, myrrh, and camphor, ingredients considered especially valuable and desirable at specific times in perfume history. Chapter 3 on race turns more specifically to the issue of identity and, drawing on older sources and more recent work by historians and anthropologists, explores the way ‘the [racial] “other” has been defined as smelling different and, almost invariably, unpleasant’, as well as ‘the rich olfactory cultures beyond the Global North’ (p. 21). This chapter is enhanced by considerations of how diet is perceived to determine racial identity through odour – with specific racial groups despised as ‘stinking’. More positively it also discusses native peoples who use smell and odour in nuanced ways to conceptualise time and the human life cycle.

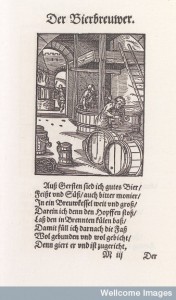

Chapter 4 traces how at different historical moments different kinds of women – virgins, virtuous women, whores, adulteresses, and witches – were supposedly identifiable by their characteristic smell, and also the historically or culturally variable positive and negative associations of perfume when used by women for adornment and seduction. Chapter 5 considers how ‘References to smell are intended to put people in their proper social place’ (p. 22). It surveys different historical standards of cleanliness, perfumed luxury, and more specifically the bad smell typically associated with the poor. Concluding with a focus on the Victorian period when the poor and working class were often believed to be oblivious to bad smells, Reinarz shows how working-class trades such as malting and brewing required trained noses to maintain rigorous quality control.

The final chapter on the smells of the city investigates historical perceptions of miasma (bad-smelling air thought to cause disease), and documents how the characteristic odours of the city became regulated by sanitary and hygiene reforms – key examples being nineteenth-century London and Paris. It also notes the increasing and still prevalent ‘sanitarian’ tendency to deodorise public spaces so that the city loses its ‘memories’ and its soul. Reinarz concludes his book with a brief reflection on the significance of the topics covered, current research, and the observation that ‘in the fields of the humanities and social sciences, [smell] has only begun to show its potential to open vast territories of exploration’ (p. 218).

This is primarily a broad survey study that synthesises existing scholarship and thus predominantly summarises and reflects on the works of others who are specialists in their particular fields of enquiry, this assuring its value as work of reference. Reinarz gives due credit to his most important sources – not only Corbin and Classen & Co. who are repeatedly mentioned, but also Annick le Guérer on smell in the philosophical tradition (1992), Susan Harvey on scent in early Christianity (2006), Christian Woolgar on smell in late medieval England (2006), Holly Dugan on perfume in the Renaissance (2011), Mark Smith on race and smell (2006), Janice Carlisle on class and smell (2004), Geoffrey Jones on the beauty industry (2010), Nigel Groom on frankincense and myrrh (1981), and Jim Drobnick’s The Smell Culture Reader (2006) – to mention some of the most frequently cited authorities. Inevitably, in areas where research is still in its early stages, this can lead to dependence on a small number of sources so that, for example, the chapter on religion leans heavily on paraphrase of Classen, Harvey, and Woolgar. This is not to diminish its usefulness in showcasing major scholarship on an important, previously neglected topic, although one suspects that the chapters on class and the city in which Reinarz was able to draw on his own historical expertise with regard to smell and Victorian culture may have afforded him more direct satisfaction. Writing a book of this kind necessarily demands a selflessness that many academics would balk at. A judicious mediating presence, Reinarz does a commendable job in representing and evaluating the current state of the discipline.

Clearly a work of this kind cannot be expected to cover everything. From my own perspective I would have liked more focus on the figure of the olfactif, the individual with a refined sense of smell, and also positive emotions connected with smells, especially fragrant smells, such as joy and pleasure. Reinarz rather dutifully rehearses factual information about the history of the modern perfume industry but neglects to say anything about the large community of perfume lovers (perfumistas) who compulsively blog and chat about their obsession with contemporary and vintage fragrances on the many dedicated internet sites. Writing about one’s own perception of fragrance, an activity that commonly draws on a highly-coloured, often elaborate descriptive and affective language, is now an internet staple, influenced in part by key figures like Luca Turin and Tania Sanchez whose best-selling perfume guide has popularised witty eloquent ways of declaring one’s perfume preferences. The related phenomenon of the modern perfume memoir (Denyse Beaulieu 2012, Alyssa Harad 2012) and the growth of organised perfume events such as seminars and workshops also bear witness to the increasing need of perfume lovers to educate their tastes and express and share their passion.

Fashion and trends in perfumery tend to echo and reinforce wider historical changes, so more acknowledgement of this by Reinarz would have been good. The modern phenomenon of niche perfumery and specialist outlets for customers who want to buy more unusual, artisanal perfumes rather than commercial brands would also have provided an opportunity for contemporary reflections on luxury, status, and difference. Reinarz mentions museums of perfumery in Grasse and Barcelona (p. 76), but neglects the Osmothèque at Versailles, the world’s most significant perfume museum with its precious holdings of vintage perfume where visitors can smell careful recreations of fragrances no longer available. Reinarz declares that odours cannot ‘be stored over time, like most other artifacts unearthed in archives’ (p. 6) While this may be true of many odorous substances exposed to the air, experts now acknowledge that, carefully stoppered and stored, perfume can be preserved for well over a hundred years.

But these are merely one researcher’s cavils about what is an extremely competent and insightful survey of the history of olfaction and, moreover, a book that will be required reading for anyone wishing to explore the social significance of smell at different historical moments.