This is a guest post by Melissa Dickson, a Postdoctoral Researcher on Diseases of  Modern Life: Nineteenth-Century Perspectives, an ERC funded project based at St Anne’s College, Oxford, investigating nineteenth-century cultural, literary, and medical understandings of stress, overwork, and other disorders associated in the period with the problems of modernity (ERC Grant Agreement Number 340121). Her main research interests are in Victorian literature and material culture, and in nineteenth-century constructions of the Orient and industrial modernity. Follow her on Twitter @melissaldickson

Modern Life: Nineteenth-Century Perspectives, an ERC funded project based at St Anne’s College, Oxford, investigating nineteenth-century cultural, literary, and medical understandings of stress, overwork, and other disorders associated in the period with the problems of modernity (ERC Grant Agreement Number 340121). Her main research interests are in Victorian literature and material culture, and in nineteenth-century constructions of the Orient and industrial modernity. Follow her on Twitter @melissaldickson

Over the last decade, the field of Victorian Studies has seen something of what has been termed a ‘material turn’, that is, an upsurge in interdisciplinary, collections-based research, which enriches our understanding of Victorian Literature while also allowing us an insight into the diverse material culture of the period. Things are the new objects of research, and much critical attention has been paid to their role in nineteenth-century literature and culture. In A Sense of Things (2003), Bill Brown argues that we have always asked things ‘to make meaning, to remake ourselves, to organize our anxieties and affections, and to sublimate our fears and shape our fantasies’. He calls attention to the myriad ways in which materiality was implicated as a constitutive force in both the literary and the social life of nineteenth-century America. But, removed from their social and cultural contexts and their ‘normal’ uses and relocated to the museums and archives of today, these objects of the past, distinguished by us as objects of interest, come to signify in new contexts, and are made to speak in new ways, through new critical lenses and through our own voices. For researchers and curators, they become objects of mystery, confusion, frustration, and joy in what are perhaps less visible webs of relations. Edwina Ehrman alluded to something similar to this, explaining that any given collection may be mediated by the idiosyncrasies and preferences of its curator. By this logic, then, we become shaping elements in our objects’ histories and how and when they are told.

Ehrman’s remarks were made during the Objects of Research: The Material Turn in Nineteenth-Century Literary Studies workshop, held at the Senate House Library in London on Monday 18th July. The workshop’s stated goal was to share knowledge about the nature and methodologies of current object-led research in Victorian Studies among researchers and curators working in this field. We asked questions about how to ‘read’ objects, how to access them, how to situate such materials within a broader historical context, and how to construct arguments drawn from object-based research. It became increasingly clear throughout the day that, as Elaine Freedgood has argued in The Ideas in Things (2006), there is a kind of history that is potentially ‘stockpiled’ in objects, and, from hats to novelty books, to railways stations and Victorian machinery in motion, our speakers demonstrated the range of emotions and the various kinds of social and cultural knowledge that become available to us through studying particular objects and their intersections with literature and people. In so doing, however, they also revealed the physical and often far more personal pleasures which are frequently implicated in this kind of research – in the proximity, the touch, and the sight of our raw materials – and the emotional and psychological connections that we, as researchers, can forge with our objects of research.

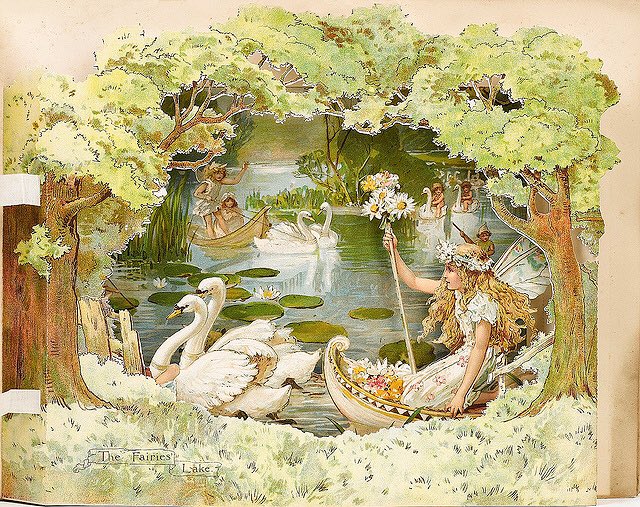

Peeps into Fairyland: A Panorama Picture Book of Fairy Stories (1895), with thanks to Rosie White

Generally, researchers purport to be objective. The objects of our research and the sensory and emotional ways we engage with them, however, raise the possibility that our subjectivity may not always be a liability. It can in fact be to our benefit, if we consider that the significance that material objects often come to hold in the intellectual and emotional life of the researchers who work with them is an interaction that not only contributes to the shaping of our ideas, arguments, and research pathways, but it becomes part of our own identities as researchers. We are, in fact, significant components in the network of social and cultural relations through which our objects function.

For more on the Objects of Research event, see the Storify here.

WORKS CITED

Bill Brown, A Sense of Things: The Object Matter of American Literature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003).

Elaine Freedgood, The Ideas in Things: Fugitive Meaning in the Victorian Novel (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006).