What is the history of emotions? And why does it matter?

As part of our first anniversary at the History of Emotions blog, I asked members and friends of the Centre for the History of the Emotions to write a paragraph or two on what they thought about the history of emotions, how they got involved in it, why it mattered, and what were their favourite publications in the field.

The dozen answers below range widely. Several are by PhD students here at Queen Mary, others are by established academics. Recurring themes include the relationship between scientific and humanistic attempts to get to grips with human mental life. The recommended reading (and viewing) includes some classics in the history of emotions and some more surprising items too from the fields of philosophy and anthropology.

This series of mini-posts starts with some warm words of support from the incoming Head of the School of History at Queen Mary, Professor Miri Rubin.

Miri Rubin

Professor of Medieval and Early Modern History, QMUL

Author of: Emotion and Devotion: The Meanings of Mary in Medieval Culture

Having the Centre for the History of Emotions, and its lively blog, among us in the School of History has been a real inspiration. We have become better historians, for being reminded of the importance – in all that we study – of tears and fears, hopes and mopes. Emotions-awareness does not redefine what we do, but it enhances our understanding and refines our sensibilities. It also makes us feel part of a vast network of lively and interesting scholars.

Rhodri Hayward

QMUL Centre for the History of the Emotions

The history of emotions is a radical discipline. It takes as its subject matter what appear at first instance, to be the most authentic and intractable aspects of our identities and reminds us that these things are transitory and contingent. It teaches us that our feelings are not determined by deep psychology or biology but are instead historical constructions borne out of an accident of our language, relationships and material circumstances. In doing this, the discipline opens up the possibility of new forms of politics and new ways of working on the self. If our inner life is determined by the world around us then the first step to radical change or personal transformation is engagement with that wider environment. And as recent work in the discipline makes clear, this wider environment that sustains emotions includes a vast range of elements from friendships and family structures to popular novels, pension schemes or animal experiments.

The basic idea that our emotions might be culturally relative was hammered into me from quite a young age but it has taken me ages to get to grips with the concept. Nationalist teachers back at school in Wales were keen to remind us that the Welsh word ‘hiraeth’ variously translated as longing, grief or homesickness had no equivalent in the English language. However it was not until I began a PhD with Roger Smith in Lancaster that I began to understand how such words were not simply rooted in different cultures or identities but also worked to construct those selfsame cultures. Smith’s Being Human: Historical Knowledge and the Creation of Human Nature (2007) provides a brilliant statement on how writing the history of psychology transforms the actual subject matter of psychology. There is no way of disentangling emotions (or for that matter any other psychological states) from their descriptions. When we write the history of the emotions, we make available novel descriptions and associations that in turn create new ways of understanding and experiencing our inner lives.

The basic idea that our emotions might be culturally relative was hammered into me from quite a young age but it has taken me ages to get to grips with the concept. Nationalist teachers back at school in Wales were keen to remind us that the Welsh word ‘hiraeth’ variously translated as longing, grief or homesickness had no equivalent in the English language. However it was not until I began a PhD with Roger Smith in Lancaster that I began to understand how such words were not simply rooted in different cultures or identities but also worked to construct those selfsame cultures. Smith’s Being Human: Historical Knowledge and the Creation of Human Nature (2007) provides a brilliant statement on how writing the history of psychology transforms the actual subject matter of psychology. There is no way of disentangling emotions (or for that matter any other psychological states) from their descriptions. When we write the history of the emotions, we make available novel descriptions and associations that in turn create new ways of understanding and experiencing our inner lives.

Although our emotional categories might be transient and rooted in particular cultures they are none the less powerful. Anyone who has lived with small children or awkward flatmates will know that statements about inner feelings (‘I feel cross’, ‘I’m disappointed’) serve as bargaining chips as we negotiate competing agendas. They also work, as the anthropologist, Vincent Crapanzano argued in his Hermes’ Dilemma and Hamlet’s Desire (1992) ‘to call the context’: announcing one’s feelings changes our understanding of a situation. Over recent years I’ve become interested in this traffic between the political shaping of the emotions and the emotional shaping of politics. Alongside the writings of Roger Smith, Thomas Dixon and Vincent Crapanzano, I have found Kurt Danziger’s work on the history of psychological objects enormously useful here (e.g. Naming the Mind). Danziger’s account of the how psychological categories are first constructed and then serve to coordinate political arguments or economic decisions is a good tool for interrogating the enforced fun of the current government’s happiness agenda.

Jen Wallis

PhD Student, QMUL Centre for the History of the Emotions

When I first mention to people that I work within the ‘Centre for the History of the Emotions’, I often get an amused smirk in response – as in ‘Gosh, they really will teach anything at universities these days’. Once you talk it over, though, they generally realise it’s not all intangible trendy theory. In the history of psychiatry, for example, emotion is at the heart (and head) of the matter: the nineteenth-century asylum (my own area of study) was a site where emotions were to be calmed – or sometimes awakened, depending on the nature of the illness – and where ideas were formulated about ‘appropriate’ emotions. Investigating the point at which an emotion crossed over from the normal to the pathological is crucial, then, in understanding nineteenth-century responses to a whole range of mental illnesses.

Though not necessarily self-consciously located within ‘the history of emotions’, Barry Reay’s Watching Hannah: Sexuality, Horror and Bodily De-formation in Victorian England is perhaps my all-time favourite book by a historian. Reay examines the photography and sketches of middle-class Arthur Munby, who was fascinated by the bodies of working-class women; his photos emphasised the muscular physique of pit-women and the calloused hands of his wife and maid, Hannah Cullwick. Munby’s emotional life comes across as a complex one: eroticised fascination for the body of the working woman, voyeuristic horror in the face of a woman who had lost her nose to lupus, and adoration for his wife, who he married in secret, her difference in social status both fetishised in Munby’s photographs and placing strict limitations on any public displays of affection.

Though not necessarily self-consciously located within ‘the history of emotions’, Barry Reay’s Watching Hannah: Sexuality, Horror and Bodily De-formation in Victorian England is perhaps my all-time favourite book by a historian. Reay examines the photography and sketches of middle-class Arthur Munby, who was fascinated by the bodies of working-class women; his photos emphasised the muscular physique of pit-women and the calloused hands of his wife and maid, Hannah Cullwick. Munby’s emotional life comes across as a complex one: eroticised fascination for the body of the working woman, voyeuristic horror in the face of a woman who had lost her nose to lupus, and adoration for his wife, who he married in secret, her difference in social status both fetishised in Munby’s photographs and placing strict limitations on any public displays of affection.

Tiffany Watt-Smith

British Academy Post-Doctoral Fellow, Department of Drama and Centre for the History of the Emotions, QMUL

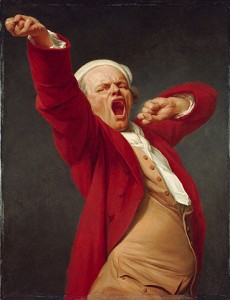

In 2009, Judge Daniel Rozak of Illinois was handing down a sentence on a felony drug charge when the defendant’s cousin, watching from the gallery, let out an enormous yawn. Thirty-three-year old Clifton Williams was promptly served with a 6-month jail sentence for contempt of court. ‘It was not a simple yawn’, the attorney’s office later explained to the incredulous Williams family. ‘It was an attempt to undermine the court’s authority’.

Yawns, flinches, shudders, sighs, smiles, tears, frowns and pouts are never ‘simple’. Like language, these fleeting emotional expressions are slippery, their meanings shifting across different contexts, times and cultures. Of course we’ll never know what Williams really felt in the moment of his yawn. Perhaps tiredness brought on the offending gesture. Perhaps his yawn spewed forth from a maelstrom of anger and frustration, manifesting as boredom, scorn and derision. But from a historian’s point of view, the feelings behind Williams’s yawn matter less than the cultural assumptions its performance highlights. Read by the Judge as an attempt to ridicule and challenge the operation of his power, Williams yawn is very revealing indeed.

Tracing the role of emotional expressions – even ones so marginal and inconsequential-seeming as yawns – in social interaction can help us understand a great deal about cultures of the past. These minor emotional skirmishes show a great deal about how power operates in any given society, how gender, race and class roles are performed, how alliances are formed, hierarchies challenged, manners regulated, expectations swerved and confidences betrayed. Emotions bind us to our communities, our relationships forged and broken on the strength of our feelings, but in reality these negotiations may be subtle ones, taking place over a quizzical look, an almost imperceptible shrug or a giggle stifled. The fact that emotional expressions are governed by rules of display determining what is appropriate or inappropriate reminds us that emotions exist in more than one dimension. We habitually think of our feelings as private, subjective experiences, yet as the history of emotions affirms, emotions are also part of a matrix of cultural identities and social interactions too.

Historians of emotion do their work in this social dimension, shining a light on what for previous generations may have been considered too trivial and too fleeting for study. One of the things historians of emotion do well is to make the familiar strange again, reminding us of the contingency of our own assumptions about feelings through comparison with the past. Over eight-hundred years ago in twelfth-century France, yawning was not an affectation of the angry and disenfranchised, but rather the mark of an ardent young lover. While in English romances unrequited lovers sighed, in Occitan they yawned for the object of their affections, as a verse written by the troubadour Arnaut Daniel in 1170 testifies:

Day-long I stretch, all times, like a bird preening,

And yawn for her

Liz Gray

PhD Student, QMUL Centre for the History of the Emotions

Emotions are personal ‘things’. They are pervasive and they are how we all connect – with each other, and with our past. They are also one of the ways, often the first way we connect with history in general. But my emotions are mine, and your emotions are yours. And the emotions I felt five years ago are related to, but not the same as, the emotions I feel today. The emotions you felt five years ago are related to, but not the same as, the emotions you feel today. So what is there to gain from studying the history of emotions?

By understanding the subjectivity of our emotions, we are able to approach history more objectively. Through studying the history of emotions we can pick apart the basis for the emotions in each historical setting. Instead of empathising with the emotional feelings we read in our sources, we can take a step back and get closer to understanding what those emotions meant to the person, people, communities we are studying. And at the same time, it allows us to take a step back and assess our own feelings and reactions towards the history we are studying.

There is one essay on the history of emotions that had a major impact on how I think about emotions during the development of my PhD project. Paul White’s essay ‘Sympathy under the Knife: Experimentation and Emotion in Late Victorian Medicine’ (in the collection Medicine, Emotion and Disease, 1700-1950, edited by Fay Bound Alberti) explores the emotions surrounding the practice of vivisection in the second half of the nineteenth century. It explores the interplay between the development of theories of emotion in the nineteenth century with the emotions elicited by the actual practice of animal experimentation. This essay drew my attention to the importance the role of emotion played even in the development of theories of emotions themselves. The suffering of animals is an emotive subject in the twentieth century, but was this the case in the nineteenth century? Did the men experimenting on animals have different emotional responses to their subjects than those protesting against their practices? If, in my studies of comparative psychology I can separate the anthropomorphic emotions from the ‘scientific’ emotions, we can get closer to the psychology that was being investigated.

There is one essay on the history of emotions that had a major impact on how I think about emotions during the development of my PhD project. Paul White’s essay ‘Sympathy under the Knife: Experimentation and Emotion in Late Victorian Medicine’ (in the collection Medicine, Emotion and Disease, 1700-1950, edited by Fay Bound Alberti) explores the emotions surrounding the practice of vivisection in the second half of the nineteenth century. It explores the interplay between the development of theories of emotion in the nineteenth century with the emotions elicited by the actual practice of animal experimentation. This essay drew my attention to the importance the role of emotion played even in the development of theories of emotions themselves. The suffering of animals is an emotive subject in the twentieth century, but was this the case in the nineteenth century? Did the men experimenting on animals have different emotional responses to their subjects than those protesting against their practices? If, in my studies of comparative psychology I can separate the anthropomorphic emotions from the ‘scientific’ emotions, we can get closer to the psychology that was being investigated.

Jane Mackelworth

PhD Student, Centre for the History of the Emotions and Centre for Studies of Home, QMUL

My interest in the history of the emotions stems from my training in both psychology and history. I graduated in psychology with the intention of studying for a doctorate in clinical psychology. However, after working in both clinical and health psychology departments I realized that this was not the right course of action for me. There was (at that time) a heavy focus on cognitive behavioural therapy which was based upon a very particular model of human behaviour. The emphasis was on a ‘scientist practitioner’ approach which stressed the ability to stand back from your clients, observe an objective detachment and apply a scientific framework to access the mind (and the problems) of the person sitting opposite you. Values such as empathy and others which derive from a more humanistic tradition were unpopular and seen as unhelpful. It felt to me as though there was little interest in attempting to uncover a person’s emotional experience. Rather the attention was on changing their thoughts, within a limited time frame, no matter how traumatic their previous experiences may have been. Emotions had become, it felt to me, rather a dirty residue.

Some years later I returned to study university to study history, undertaking an MA in Historical Research with a focus on social and cultural history. I realized very quickly how powerful studying history could be. Rather than just an endeavour to find out what happened history is an attempt to make meaning of the past and to slip into (albeit briefly) past minds and bodies. It quickly became obvious to me that it was impossible to understand the past without attempting to enter into the mind-set or the way of being of its inhabitants. One of the books which demonstrated this to me most clearly was Lyndal Roper’s Witch Craze (2004). As post-enlightenment beings it can be hard for us to make sense of magical beliefs. And it can be all too easily approached from a rationalist paradigm. With the wish to work out ‘what was really going on’. Trying to apply it to our modern day world, to find the parallels. But really the only way that we can understand beliefs in magic, and in witches is to suspend what we know now. And to understand it how it was then. Roper attempts to enter into the emotional mind-set of the women, and men, involved to explore the emotions at play, to understand both the fear of witches and also the belief that one was a witch. So just one example, she looks at the meaning attached to gifts given by witches:

Some years later I returned to study university to study history, undertaking an MA in Historical Research with a focus on social and cultural history. I realized very quickly how powerful studying history could be. Rather than just an endeavour to find out what happened history is an attempt to make meaning of the past and to slip into (albeit briefly) past minds and bodies. It quickly became obvious to me that it was impossible to understand the past without attempting to enter into the mind-set or the way of being of its inhabitants. One of the books which demonstrated this to me most clearly was Lyndal Roper’s Witch Craze (2004). As post-enlightenment beings it can be hard for us to make sense of magical beliefs. And it can be all too easily approached from a rationalist paradigm. With the wish to work out ‘what was really going on’. Trying to apply it to our modern day world, to find the parallels. But really the only way that we can understand beliefs in magic, and in witches is to suspend what we know now. And to understand it how it was then. Roper attempts to enter into the emotional mind-set of the women, and men, involved to explore the emotions at play, to understand both the fear of witches and also the belief that one was a witch. So just one example, she looks at the meaning attached to gifts given by witches:

In such interactions, objects which might seem trifling were invested with intense emotional significance. They acted as the litmus test of relations between people. This was why so much of the substance of witchcraft testimony apparently concerns the giving of objects of minute value. With the witch giving went wrong.

I think that history is at its most powerful in its study of things that we now take for granted, as though they are real, or constant. Where the emotions are taught elsewhere it is almost always from a realist point of view, as though this is fact. And so today, for example, our emotions, particularly those thought of as ‘disordered’ are seen as stemming from our biological make up, our genes. Yet even a brief historical glimpse at the experience of emotions challenges this. Emotions are always given meaning in a particular time and context. So, for example, we learn a lot about a society by seeking to understand why the emotions accompanying hysteria were generally ascribed to women.

Another piece of work I read recently and enjoyed was an article in Social and Cultural History by Claire Langhamer entitled ‘Love, Selfhood and Authenticity in Post-War Britain’. In this article, Langhamer explores the ways in which our understanding of love changed over the twentieth century. She argues that it has become seen as a route to self-actualization, thus it has become more about a route to personal fulfillment or liberation. She suggests that Love came to be seen increasingly as being about ‘chemistry’ and ‘emotional intimacy’ rather than ‘respect’ and ‘affection’ (p. 280). This also ties in with a greater focus in the twentieth century on the right to be happy and fulfilled.

Realising that emotions are culturally, and historically experienced is a curious realization. It is immensely liberating, because we realize that the meaning we give to emotions (and therefore the way that we experience them) is so intrinsically socially constructed. However, this moment of liberation is so fleeting because it is followed so quickly by the overwhelming sense that we can only ever be products of our age, so powerful is cultural and social conditioning. Thus, the emotions that we feel now are as real (and as different) as the emotions that were felt in the past.

Carolyn Burdett

Department of English and Humanities, Birkbeck, University of London

For me, thinking about emotions and/in history began with empathy. In November 2004, a US literary scholar, Suzanne Keen, sent a request to the VICTORIA listserv explaining that she was writing a book about empathy and the novel, and asking for respondents’ experiences of empathising while reading Victorian fiction. Her request produced a long debate, full of thoughtful and intelligent insight about reading novels. As I followed it, though, I began to feel distracted by the way in which the terms sympathy and empathy were being used. Sometimes they seemed to be interchangeable, while sometimes respondents stressed differences between them; at times, too, they were applied to either Victorian authors or to Victorian readers or to both. What struck me most, was that I couldn’t recall ever coming across the term empathy in the literature of the period. Did the Victorians empathise, I wondered; and the OED confirmed that they indeed did not. Empathy was coined in 1909 by the British-born, US-based experimental psychologist, Edward Bradford Titchener, to translate a German word, Einfühlung, which was in turn first used as a noun in an 1873 work, On the Optical Sense of Form, by the German aesthetician Robert Vischer.

My interest in empathy was also fuelled because it seemed to be becoming a more audible word in the wider culture – and especially in the political discourse of twenty-first-century Britain. Some commentators date a shift in political rhetoric – to one more overtly ‘emotional’ – to the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, and the way in which the then Prime Minister, Tony Blair, led public reaction to her death. More intriguing for me was another news story, again from 2004: namely the sacking from her opposition front bench position of the Liberal Democrat MP, Jenny Tonge. Her dismissal followed remarks she made about Palestinian suicide bombers in the Occupied Territories, when she commented: ‘If I had to live in that situation – and I say that advisedly – I might just consider becoming one myself’. Much of the subsequent debate turned on the question of whether a distinction could be drawn between empathy for, and approval of, suicide attacks. Tonge herself insisted that ‘I feel with just as I don’t agree with’. She substantiated her claim by explicitly differentiating between empathy with and sympathy for the suicide bombers’ actions. She did not, she said, sympathise with them.

My interest in empathy was also fuelled because it seemed to be becoming a more audible word in the wider culture – and especially in the political discourse of twenty-first-century Britain. Some commentators date a shift in political rhetoric – to one more overtly ‘emotional’ – to the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, and the way in which the then Prime Minister, Tony Blair, led public reaction to her death. More intriguing for me was another news story, again from 2004: namely the sacking from her opposition front bench position of the Liberal Democrat MP, Jenny Tonge. Her dismissal followed remarks she made about Palestinian suicide bombers in the Occupied Territories, when she commented: ‘If I had to live in that situation – and I say that advisedly – I might just consider becoming one myself’. Much of the subsequent debate turned on the question of whether a distinction could be drawn between empathy for, and approval of, suicide attacks. Tonge herself insisted that ‘I feel with just as I don’t agree with’. She substantiated her claim by explicitly differentiating between empathy with and sympathy for the suicide bombers’ actions. She did not, she said, sympathise with them.

This was the starting point for my research into what happens to a distinctively Victorian notion of sympathy in the final decades of the nineteenth century, and the coining of empathy in the first decade of the twentieth. In the meantime, interest in, and research about, empathy has boomed. In 2005, a quick search of the British Library’s Integrated Catalogue for ‘empathy’ produced 179 hits. Today, the BL’s new (and admittedly more inclusive) ‘Main Catalogue’ shows over 5,000 results. The tab showing ‘Creation date’ is interesting:

- Before 1972 (17)

- 1972 To 1985 (20)

- 1985 To 1993 (128)

- 1993 To 2001 (888)

- After 2001 (4,216)

Much of the excitement about empathy in the last decade or so has stemmed from recent neuroscientific research and, in particular, the use of fMRI scans of the brain. Beautiful coloured patterns bleed over the screen showing mimetic ‘mirror neurons’ at work: we are hard-wired for empathy, it seems. Mirror neurons explain the evolution of language, and the development of culture, we hear. For some enthusiasts, mirror neurons are at the centre of a neuroscientific revolution which teaches that ‘We are nothing but a pack of neurons’ (according to V. S. Ramachandran, the ‘Marco Polo of neuroscience’ as Richard Dawkins named him, Director of the Centre for Brain and Cognition, at UC San Diego).

Much of the excitement about empathy in the last decade or so has stemmed from recent neuroscientific research and, in particular, the use of fMRI scans of the brain. Beautiful coloured patterns bleed over the screen showing mimetic ‘mirror neurons’ at work: we are hard-wired for empathy, it seems. Mirror neurons explain the evolution of language, and the development of culture, we hear. For some enthusiasts, mirror neurons are at the centre of a neuroscientific revolution which teaches that ‘We are nothing but a pack of neurons’ (according to V. S. Ramachandran, the ‘Marco Polo of neuroscience’ as Richard Dawkins named him, Director of the Centre for Brain and Cognition, at UC San Diego).

In its first uses, though, empathy was primarily associated with aesthetic experience. In the hands of its initial exponent in Britain, the writer Vernon Lee, empathy hovered uncertainly between being a distinctively corporeal reaction to looking at beautiful forms which affected the viscera and thus feelings of health and well-being, and a more opaque mental experience which might ultimately explain the human impulse to metaphor and symbolisation. Lee, like many late Victorians, moved between enthusiastic hope that human experience might, eventually, be explicable in terms of verifiable, testable and indisputable physiological facts and a dogged conviction that the diversity, inventiveness and strangeness of life, human feelings and histories called for other ways of seeing things. When we contemplate empathy today, this Victorian debate remains a salutary case, reminding us that how our brains fire up is likely just one small part of the story.

Chris Millard

PhD Student, QMUL Centre for the History of the Emotions

As human beings inhabiting the twenty-first century, emotions are part of the very fabric of our existence. While contemporary experts seek to root our emotional responses in some deep evolutionary past or specific neurochemical reaction (or both), the history of emotions can show how these claims have a history of their own. Through the history of emotions, the varied ways in which human beings have understood themselves across time and space be analysed. We can seek out different understandings of emotional states that have occurred in the past without attempting to collapse them into more or less approximate versions of today’s emotions du jour. Our understanding of emotional states constitutes a substantial proportion of how we understand ourselves, and unthinkingly to hand over interpretive authority in this area to neurochemists or evolutionary psychologists seems misguided at best. An appropriately historical understanding of emotions leads to a stress on the contingency and malleability of the intellectual systems and shorthand we use in order to make sense of internal mental, psychological and emotional states.

This has an important political dimension. Criticising the Coalition Government’s Happiness Index or Paul Ekman’s reductionist emotion-faces is all very well, but meaningful and long-lasting change is most likely to come from an understanding of the historically specific assumptions that enable interior states to be flattened out, quantified, tabulated, computed or otherwise deployed to buttress any number of political projects. Such moves are only credible because of long, complicated, historical processes. These assumptions, their sources of credibility and their various consequences are a key target for the history of emotions. As philosopher and historian Michel Foucault has said: ‘[c]ritique is not a matter of saying that things are not right as they are. It is a matter of pointing out on what kinds of assumptions, what kinds of familiar, unchallenged, unconsidered modes of thought the practices that we accept rest.’

This has an important political dimension. Criticising the Coalition Government’s Happiness Index or Paul Ekman’s reductionist emotion-faces is all very well, but meaningful and long-lasting change is most likely to come from an understanding of the historically specific assumptions that enable interior states to be flattened out, quantified, tabulated, computed or otherwise deployed to buttress any number of political projects. Such moves are only credible because of long, complicated, historical processes. These assumptions, their sources of credibility and their various consequences are a key target for the history of emotions. As philosopher and historian Michel Foucault has said: ‘[c]ritique is not a matter of saying that things are not right as they are. It is a matter of pointing out on what kinds of assumptions, what kinds of familiar, unchallenged, unconsidered modes of thought the practices that we accept rest.’

Mark Honigsbaum

Former PhD Student of QMUL Centre for the History of the Emotions; University of Zurich

Long before I became a journalist and even longer before I became an historian, my first love was moral and political philosophy and, though I didn’t realise at the time, it was via Hume, Rousseau, Marx, and Mill that I first became interested in the place of emotions in history. The emotions, or the ‘passions’ as Hume called them, were central to these thinkers’ visions of a more just and moral society, hence Marx’s conviction that capitalism was founded on the ‘alienation’ or misery of it’s workers and Mill’s concern to maximise the happiness of the greatest number.

Today, such preoccupations are more present in our culture than ever. From David Cameron’s ‘well-being’ index to the ‘fury’ at bankers’ bonuses and the ‘anger’ felt in Greece and elsewhere at neo-liberal austerity programmes, we are used to the idea that emotions are important objects of epidemiological regulation. But it wasn’t until I read William Reddy’s The Navigation of Feeling that I realised that this had not always been the case.

Focussing on the French Revolution, Reddy argues that to seek to explain the ‘Reign of Terror’ only in sociological terms is to miss something about the sea change in emotional attitudes that took place in France between 1650 and 1789. Founding his argument on an analysis of ’emotives’ or emotional gestures and utterances that have the capacity to alter the states of the speakers from whom they derive, Reddy shows how the revolution brought about a ‘flowering of sentimentalism’ – an enthusiasm for emotional expression and intimacy that was anathema to the old courtly, pre-revolutionary codes of honour and restraint. Far from being an ‘Age of Reason’, this was a period that encouraged emotional incontinence as never before.

Focussing on the French Revolution, Reddy argues that to seek to explain the ‘Reign of Terror’ only in sociological terms is to miss something about the sea change in emotional attitudes that took place in France between 1650 and 1789. Founding his argument on an analysis of ’emotives’ or emotional gestures and utterances that have the capacity to alter the states of the speakers from whom they derive, Reddy shows how the revolution brought about a ‘flowering of sentimentalism’ – an enthusiasm for emotional expression and intimacy that was anathema to the old courtly, pre-revolutionary codes of honour and restraint. Far from being an ‘Age of Reason’, this was a period that encouraged emotional incontinence as never before.

Put that way, Reddy’s thesis sounds simplistic. Didn’t we always knows that the French Revolution fed off the passions of the mob? Yes, but until Reddy we didn’t realise how far these passions were products of particular historical regimes and political and cultural practices. Nor did we really appreciate how the mere act of emoting could change what was actually felt. As Reddy puts it, ‘emotives are influenced directly by and alter what they “refer” to… emotives do things to the world.’

There has been much debate since about how far historians should be prepared to run with the emotives. Reddy himself presented his theory as an argument ‘against constructionism’ and at times seems to come perilously close to endorsing an essentialist view of the emotions. However, I would argue that Reddy’s real aim is to outline a third way between essentialist and Foucauldian constructivist positions by showing how power is always located in emotional control – in other words, in who gets to express and who must repress certain feelings.

At a time of great financial and political uncertainty, when we are daily being urged by Cameron and others to ‘calm down’ lest we become infected by Greek emotionalism, these insights are more pertinent than ever. I also like to think that Mill would have had sympathy with Reddy’s approach. ‘Ask yourself whether you are happy,’ he once famously asked himself, ‘and you cease to be so.’ Now that’s what I call an emotive.

Rebecca Kingston

Political Science, University of Toronto

Author of Public Passion: Rethinking the Grounds for Political Justice

In his recent inaugural lecture as Chichele Chair of Social and Political Theory at Oxford University, Jeremy Waldron called on political theorists to abandon almost exclusive focus on questions of virtue (or character) and ideas of justice and liberty, issues which dominated the field throughout most of the twentieth century, and instead refocus study on questions related to the practice of political institutions (separation of powers, judicial review, etc). The underlying justification for advocating this turn rested on the practical issue that we are living in societies where people disagree and the most important political questions facing us today involve how we come to reasonable accommodation through our shared authoritative institutions (rather some ideal form of dispute resolution). While laudable in its objective to move the field away from excessively abstract theorising, this position also demonstrates some blindness to what is central to the practice of politics and the working of institutions, and that is emotions that shape and are shaped by the political process.

In this context, the history of emotions matter because in a general way these studies help to demonstrate that ultimately individuals and groups give meaning to the institutions and practices that shape their lives. More specifically, though, in terms of my field of political theory, these studies can demonstrate that institutions are also limited in what they can do and that there is paradoxically both a certain hubris and excessive humility in thinking that political challenges can be resolved by institutional arrangements.

There is hubris because in the face of varied emotional responses and cultural contexts similar institutions function in vastly different ways; and there is excessive humility because greater focus on human emotion in history provides greater insight into ways in which we can move beyond traditional limits of political goods in security and liberty, and seek new goals of emotional wellbeing that can be effected by a much broader array of political and social strategies.

If there is any writer who has most influenced me in my reflections and for whom I have the greatest awe and respect it must be Jonathan Lear. My reading of his book Aristotle: The Desire to Understand marks a turning point in my intellectual development as it brought to me an understanding of the importance of emotion even at the core of intellectual endeavour. His more recent work Radical Hope I consider to be a masterpiece as it weaves together a deep understanding of emotional life as irreducibly tied to questions of moral philosophy and the good life and driven by a deep sense of humanism.

Jules Evans

Policy Director, QMUL Centre for the History of the Emotions

Author of Philosophy for Life, and Other Dangerous Situations

I’m probably the least qualified in the Centre to answer the question, so let me instead say what interests me about the history of the emotions. I am particularly interested in cognitive psychology, and the intersection between our biology and our beliefs and values. Our minds, bodies and emotions are deeply affected by the meaning we ascribe to events – and that meaning is constantly changing through culture and history. We can uncover or excavate the cultural constructions that shape our emotions. The point of doing that, for me, is to help liberate us from those constructions that serve us least well and cause us most suffering.

In terms of my favourite work of the history of the emotions, I think it would be Adam Curtis’ BBC documentary, The Century of the Self – the first bit of history of emotions I ever encountered, which left a lasting impression on me and many other people who saw it.

Thomas Dixon

Director, QMUL Centre for the History of the Emotions

For me, the point of studying the history of emotions is to liberate ourselves from contemporary psychology. By anatomising the feelings of the past, pulling apart the beliefs, bodily states, physical places and material cultures of which they were composed, we can undermine the idea that there are universal or ‘basic’ hardwired emotions that are felt by all people in all places. To use history imaginatively, to inhabit the worldviews and mental pictures of the people whose lives and ideas we study, is simultaneously to understand the past and to destabilise the present. We learn that what we feel now, how we feel it, and what we think our feelings reveal and express, is historically contingent and far from universal. Because our beliefs about our own mental states are themselves inescapable constituents of our mental lives – including, for instance, the belief in the power of involuntary invisible entities called ‘emotions’ – to study the history of ideas about emotions is itself to study the history of emotional experiences.

I first became interested in the history of emotions myself via the history of ideas, studying for my PhD between 1996 and 2000. At that time, the book that had the biggest impact on my thinking was the ground-breaking philosophical work by Robert Solomon, The Passions: Emotions and the Meaning of Life. Solomon’s book, first published in 1976, was one of the earliest, and the most influential, in a series of studies through which the emotions, previously side-lined by analytic philosophers, made their way into the philosophical mainstream. Solomon’s basic idea that emotions are both cognitive and voluntary – that they are thoughts and actions, rather than mere involuntary feelings – drew on both Stoic and existentialist philosophical ideas. Among pioneering historians of emotions, the author I would most strongly recommend is the French historian of the Annales school, Lucien Febvre. In his 1941 essay, ‘La sensibilité et l’histoire’, Febvre asked how the historian could reconstitute the emotional life of the past in a more discriminating manner. Febvre’s writings on psychology and history are polemical and penetrating. They are available in an English-language edition with an introduction by Peter Burke, first published in 1973, entitled A New Kind of History.

I first became interested in the history of emotions myself via the history of ideas, studying for my PhD between 1996 and 2000. At that time, the book that had the biggest impact on my thinking was the ground-breaking philosophical work by Robert Solomon, The Passions: Emotions and the Meaning of Life. Solomon’s book, first published in 1976, was one of the earliest, and the most influential, in a series of studies through which the emotions, previously side-lined by analytic philosophers, made their way into the philosophical mainstream. Solomon’s basic idea that emotions are both cognitive and voluntary – that they are thoughts and actions, rather than mere involuntary feelings – drew on both Stoic and existentialist philosophical ideas. Among pioneering historians of emotions, the author I would most strongly recommend is the French historian of the Annales school, Lucien Febvre. In his 1941 essay, ‘La sensibilité et l’histoire’, Febvre asked how the historian could reconstitute the emotional life of the past in a more discriminating manner. Febvre’s writings on psychology and history are polemical and penetrating. They are available in an English-language edition with an introduction by Peter Burke, first published in 1973, entitled A New Kind of History.

Febvre’s 1941 essay was an invitation to his fellow historians to get to work on this fascinating new field of history; to examine representations of emotions and sensibility in conduct books, court records, paintings, sculpture, music, and novels. ‘I am asking for a vast collective investigation to be opened,’ he wrote, ‘on the fundamental sentiments of man and the forms they take. What surprises we may look forward to!’

Pingback: What is the History of Emotions? » Pouvoir des arts

Pingback: 10 links for May — News from Somewhere

Pingback: What is the history of emotions? Part III | The History of Emotions Blog

Pingback: What is the history of emotions? | ACCESS

Pingback: The uses of a history of emotions « Serendipities