Laura Gowing is Professor of Early Modern British History at King’s College London. Here she reflects on the meaning of friendship in the early modern era, and the challenge of interpreting the records, objects, and gestures through which historians can learn about it.

Laura Gowing is Professor of Early Modern British History at King’s College London. Here she reflects on the meaning of friendship in the early modern era, and the challenge of interpreting the records, objects, and gestures through which historians can learn about it.

__________

Friendship in the early modern era – c. 1500-1750 – poses two great challenges to us: how to imagine it, and how to find it. So much of the household, the community, and the economy was explicitly structured around the patriarchal family that the wider bonds of sociability left fewer records; while everyone was taught how to be a good son, father, wife, mother, or child, only a few elite men seem to have contemplated the art of friendship.

For noblemen and gentry, friendship carried great political weight. Courtiers practiced how to admire the king’s favourite, in the hope of gaining some clout. The whole weighty system of patronage in state and church depended on networks of friends. For people like this, it’s easy to see how friendship was at once instrumental and emotional. For women at this level, too, the bonds of friendship could embody political advantage: when Lady Anne Clifford was a young woman at court in the early 17th century, her mother urged her to sleep in the room with Arbella Stuart, the woman she considered most likely to gain their family a foothold in the new queen’s household. When Anne failed, she wrote an apologetic letter home.

But what of those for whom friendship brought less obvious gains – plebeian men, and most women? One way round this has been the examination of legal documents, and particularly wills. It’s possible to trace the networks of people who witness each other’s wills, or who appear in litigation together – although the high mobility of many early modern societies militates against this. Digitisation of records is making this much easier, too. And from these kind of records, some sense of how people were connected can be built up.

What we’ve learnt has been quite suprising. Firstly, despite the distances people regularly put between themselves and their birthplaces, often ties were retained, not just with family but with local friends and connections. London, the end point of so many migratory journeys, ended up containing little hubs of Yorkshire, Wales or Essex – or Paris. Those old ties from home were the foundation of marriage, apprenticeships, and financial credit. Secondly, looking at family documents has reaffirmed the importance of wider kin. This was a world of nuclear families, with households staying surprisingly small and confined to two generations; yet those families, locally or across many miles, maintained links with their siblings, parents, cousins, old neighbours, and a whole host of others. Frequent early deaths and remarriages extended those networks even more. Some used letters, but many more depended on unplanned visits and word of mouth.

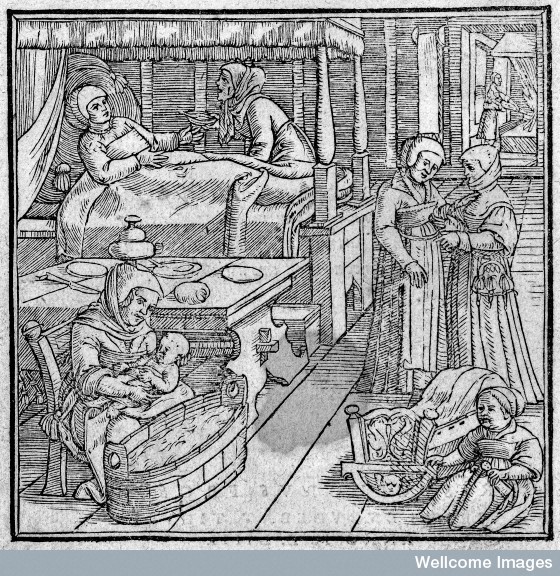

What, then, did a friend mean to the villagers and townspeople of early modern England? Its most familiar meaning was indeed an instrumental one, one that carried value: it meant those people who had an interest in your future, and specifically, your marriage. We think of marriages as private, personal unions, but for early modern people, they were public. Peaceful households meant a functional community and an orderly nation. Friends helped link the intimate to the wider world. Friends in marriage were sometimes relatives, sometimes not; one 16th century London woman found that the relatives of her dead fiancé became the friends of her next marriage, having financial entanglements with her already. Friends might provide a marriage portion, lend money, or find apprenticeships or service; and when things went wrong, they were ready to speak a warning word in an errant husband or wife’s ear. The same was true at childbirth, which was one of the few times and places which was largely single-sex. In this women’s world, the choice of who to invite to the ritual of lying-in could have implications for neighbourhood life for years to come. The results ranged from bad dreams to accusations of witchcraft.

Gossips feasting and women helping a newly delivered mother. Detail from the frontispiece for Jacob Rueff, De conceptu et generatione hominis (Zurich, 1554). Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

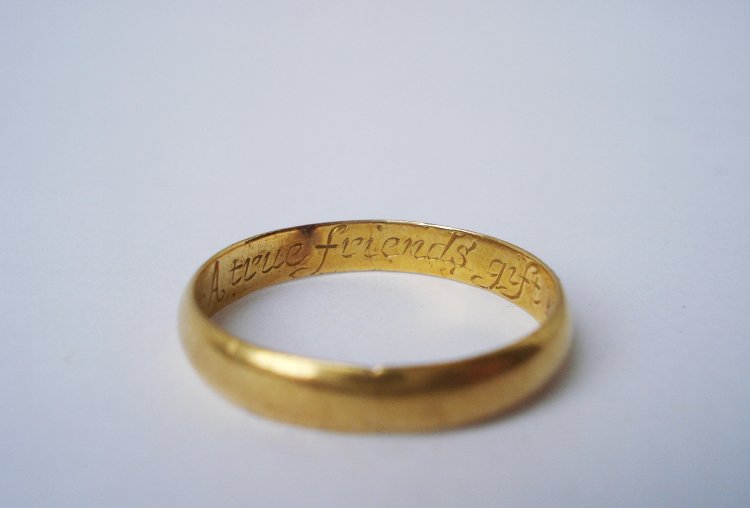

So the term ‘friend’ had meanings a good deal wider than it does today; it encompassed financial investment and value in a way we would, perhaps, be less happy with. But in this world of high mobility and limited literacy, the value of friendship was truly inestimable. A good friend would guarantee your reputation, or preserve your ‘credit’: a measure not only of who believed in you, but how much you were worth. And that creditworthiness was necessary to ordinary people and to women as well as to those in the inner circles of political power.

Most recently, historians have started to try to recapture the physical dimensions of friendship. Gestures are often as transient as emotions, yet history has preserved something of the meaning of the friendly kiss, the handshake, the doffing of the hat with respect, if only through the attacks on people who did it wrong. In those gestures, imbalances of power were displayed, and sometimes transcended, through ritual. The archives of lawsuits over marriage, property and verbal insult have turned out to be an excellent source for details like this. In the background of disputes, we can see, for example: a man taking his friend to visit a young woman he is interested in courting, and staying in a bed with him at her home; a woman testifying to her close friend’s misery over a planned marriage; women pushing against each other and hissing insults as they settle into a pew for Sunday service.

Historians of the self have imagined early modern selfhood to be best understood in the context of ‘embeddedness’, whereby every person saw their individual identity through the lens of family, friends and community. In densely-populated houses, shared beds and crowded marketplaces, in a world where privacy was a protean concept, this had a physical meaning as well as a conceptual one. Emotions had strong physical corollaries in early modern culture; broken hearts were understood as truly damaged; alongside tracking down the actual words people used about their friends, we need their gestures of friendship.

Further reading

Karen Harvey (ed), The Kiss in History (Manchester University Press, 2005)

Laura Gowing, Common Bodies: Women, Touch and Power in 17th Century England (Yale University Press, 2003)

Alan Bray, The Friend (University of Chicago Press, 2003)

Amanda E. Herbert, Female Alliances: Gender, Identity, and Friendship in Early Modern Britain (Yale University Press, 2014)

__________

Follow Laura Gowing on Twitter @LauraGowing

Return to: Five Hundred Years of Friendship at the History of Emotions Blog