![]() Dr Antonella Liuzzo Scorpo of the University of Lincoln is a medieval historian with expertise in the histories of emotion, faith and friendship.

Dr Antonella Liuzzo Scorpo of the University of Lincoln is a medieval historian with expertise in the histories of emotion, faith and friendship.

She is the author of a new book on Friendship in Medieval Iberia. Here she explores the meanings of friendship in the medieval world.

__________

As a cultural historian interested in friendship and social networks, I was pleased and excited when I heard about the new BBC Radio series exploring friendship since the sixteenth century. The influence of classical thought – especially Aristotle and Cicero– persisted throughout the early modern period, but what happened between these two periods? How did the Middle Ages shape, transform and challenge ideas of friendships which would pass onto modernity?

Scholarship on friendship in the Middle Ages suggests that interpersonal relationships in Western Europewere mostly based on a shared sense of belonging to the same local, religious, professional or ethnic communities. In most cases these communities coexisted and overlapped, thereby helping to shape a complex set of multiple identities.[1] Friendships were not restricted to exclusively civic and political fields, as most of the ancient Greek philosophers believed, but instead, influenced by the predominant Christian mentality, they also acquired spiritual and in some cases mystical connotations.

In the early Middle Ages, amicitia (friendship) was mainly regarded as a contractual link with utilitarian goals, which included economic and military support. It was seen as a permanent agreement, which in some instances was even transmitted as an inheritance. Amicable relationships were equalled only by kinship, blood ties, godfatherhood and vassalic networks. Moreover, while some friendships were legitimized on the basis of religious agency, as with the crusaders and the military orders, others were accepted as beneficial purely for the pleasure that they could generate.[2]

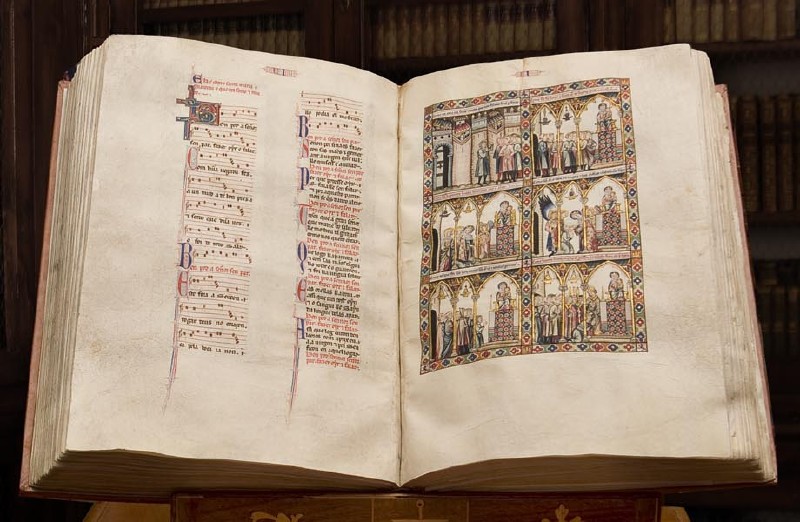

Facsimile of Cantigas de Santa Maria. Ms. T.j.I (“E2”). Real Biblioteca del Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial (San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Spain).

In different types of sources produced in Western Europe throughout the medieval period, the lexicon of friendship defined a wide and varied range of relationships, including amorous and sexual bonds; tutorship and patronage; diplomatic agreements; companionships of arms and monastic brotherhoods, among others.[3] There were also cases of ‘friendships in absence’ in which those involved did not know each other in person and yet they addressed each other as friends. The epistolary exchanges of Peter of Celle, Pope Gregory VII and John of Salisbury, St. Anselm and Bernard de Clairvaux, are significant examples, even if the language of friendship was mostly used as a rhetorical device with broader social and political implications.[4]

Anthropological approaches have led historians to argue that friendship was often dependent on other types of bonds and frequently used as an ennobling rhetorical tool. However, more recent studies have challenged those ideas to consider, instead, friendship as a distinct category of political and social networks.[5] This multi-layered panorama becomes more intricate when considering regional peculiarities. A particularly fascinating, and yet understudied, case is that of medievalIberia, which was geographically and politically a fringe of Europe, while occupying a pivotal role within theWestern Mediterranean world.

Amicitia, in Latin, means friendship in Castilian, and friendship, according to Aristotle, is a virtue which is intrinsically good in itself and profitable to human life and that, properly speaking, it arises when one person who loves another is beloved by him, for, under other circumstances, true friendship could not exist; and therefore he stated that there is a great difference between friendship, love, benevolence and concord.[6]

One might be surprised to discover that the definition given above appears in the Siete Partidas, a thirteenth-century Iberian law code aimed at regulating public and private lives of all the subjects under Castilian authority. The law explained the classical origins of friendship; it also defined its categories and warned about the necessary proofs and required norms to establish and preserve it. What is noteworthy is that friendship occupied a central role in the legal, historiographical and literary production of a growing political reality – theKingdom ofCastile – the stability of which required multiple means of legitimization.

Drawing on some of the encyclopaedic masterpieces produced in the scriptorium of ‘The Wise’ and ‘The Learned’ King, Alfonso X of Castile (1252-84) in a period later labelled the ‘Thirteenth-Century Renaissance’, my forthcoming book, Friendship in Medieval Iberia: Legal, Historical and Literary Perspectives discusses precisely how friendship was conceptualized, experienced and represented in the cultural melting-pot of such a vibrant enclave in which ‘emotional communities’ – to adopt Rosenwein’s definition – were structured around perceived similarities, as well as around costumes and practices dictated by habits, acculturation and pragmatic choices.[7]

There were frequent overlaps between categories and typologies such as friends, counsellors and companions; cases of religious, political and military friendships; inter-faith and gender relationships. Nonetheless, their constitutive elements – loyalty, trust and keeping secrets – and the threats which could undermine them remained the same in time and across geographical and cultural frontiers. Emotional connections co-existed with economic, political and legal structures within which individuals and communities found protection, as well as material, spiritual and personal support. Moreover, while norms and rituals such as banquets, vows, kisses and public celebrations were commonly recognized as tokens of friendship, the boundaries between individual and public experiences of friendship were often blurred.[8] The case of medieval Iberia – a receptacle of classical ideas, near-Eastern traditions, past and contemporary trans-Pyrenean trends – provides an invaluable contribution to the study of the much more complex political, social and cultural world of the Western Mediterranean and its distinctive, and yet very recognizable, social networks.

Today, as with the past five hundred years and before, networks of friendships have supported the development of individual and group identities; they have helped men and women to pursue their spiritual and emotional quests; to work towards political and social goals; to overcome difficulties and desolation; and to develop their own selves either by mirroring themselves into an Aristotelian “other self” or by framing distinct spaces of ‘otherness’. Even though meanings and experiences of friendship have evolved and transformed over the centuries, their focal position in the construction of both individuals and societies has never been challenged.

[1] Reginald Hyatte, The Arts of Friendship: The Idealization of Friendship in Medieval and Early Renaissance Literature (Leiden; New York: E. J. Brill, 1994); Friendship in Medieval Europe, ed. Julian Haseldine (Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 1999); Friendship in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Age, ed. Marilyn Sandidge and Albrecht Classen (Berlin and New York: de Gruyter, 2010). The latter includes a chapter on Iberia: Antonella Liuzzo Scorpo, ‘Spiritual Friendship in the Works of Alfonso X of Castile: Images of Interaction between the Sacred and Spiritual Worlds of Thirteenth-Century Iberia’, in Friendship in the Middle Ages, pp. 445–77.

[2] Klaus Oschema, ‘Reflections on Love and Friendship in the Middle Ages’, in Laura Gowing, Michael Hunter and Miri Rubin (eds), Love, Friendship and Faith in Europe, 1300-1800 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), pp. 43–65.

[3] Huguette Legros, ‘Le vocabulaire de l’amitié et son évolution sémantique au cours du XII siècle’, Cahiers de Linguistique Hispanique Médiévale 23 (1980): pp. 131–39 ; Gervase Mathew, ‘Ideals of Friendship’, in John Lawlor (ed.), Patterns of Love and Courtesy, Essays in Memory of C. S. Lewis (London: Edward Arnold, 1966), pp. 45–53, at. p. 46.

[4] The letters of Peter of Celle, ed. J. Haseldine (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001); Haseldine, ‘Understanding the Language of Amicitia. The Friendship Circle of Peter of Celle (c.1115-1183)’, Journal of Medieval History, 20 (1994): pp. 237–60; Gregory VII, The Correspondence of Pope Gregory VII: Selected Letters from the Registrum, trans. E. Emerton (New York: Octagon, 1966); J. McLoughlin, ‘Amicitia in Practice: John of Salisbury (c.1120-1180) and His Circle,’ in David G. Allen and Robert A. White (eds), Traditions and Innovations: Essays on British Literature of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance (Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press, 1990), pp. 165–81. See also J. Haseldine, ‘Friendship, Intimacy and Corporate Networking in the Twelfth Century: The Politics of Friendship in the Letters of Peter the Venerable’, English Historical Review, 126 (2011): pp. 251–80.

[5] J. Haseldine, ‘Friendship Networks in Medieval Europe: New Models of a Political Relationship’, AMITY: The Journal of Friendship Studies, 1(2013): pp. 69-88.

[6] Las siete partidas del Rey don Alfonso el Sabio: cotejadas con varios codices antiguos por la Real Academia de la Historia (Madrid: Imprenta Real, 1807), Book IV, title XXVII, law I. For an English translation see Alfonso X, The Siete Partidas, ed. Robert I. Burns, trans. Samuel Parsons Scott, 5 vols (Philadelphia:University ofPennsylvania Press, 2000), vol. 4, p. 1003.

[7] A. Liuzzo Scorpo, Friendship in Medieval Iberia: Legal, Historical and Literary Perspectives (Farnham: Ashgate, 2014); B.H. Rosenwein, Emotional Communities in the Early Middle Ages (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2006).

[8] Medieval Concepts of the Past: Ritual, Memory, Historiography, ed. Gerd Althoff, Johannes Fried. and Patrick Geary (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), pp. 71–88.