Barbara Taylor is Professor of Humanities at Queen Mary, University of London. She is an expert on Mary Wollstonecraft and a historian of both feminism and psychoanalysis. She is a contributor to Episode 5 and Episode 14 of ‘Five Hundred Years of Friendship’.

Barbara Taylor is Professor of Humanities at Queen Mary, University of London. She is an expert on Mary Wollstonecraft and a historian of both feminism and psychoanalysis. She is a contributor to Episode 5 and Episode 14 of ‘Five Hundred Years of Friendship’.

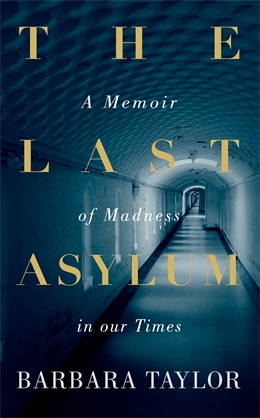

Her most recent book – The Last Asylum: A Memoir of Madness in our Times – is a personal, political and historical reflection on her own time as an asylum patient at Friern mental hospital in the 1980s. In this short extract – available in a longer version on the Guardian website – she writes about the unexpected experience of making friends with her fellow patients, including a woman called Magda.

__________

I met Magda a few days after my second admission. I was reading in the dorm when a handsome middle-aged woman presented herself to me. She was beautifully turned out in a blue-silk kaftan, with a silver-and-turquoise necklace and an armload of silver bracelets. She smiled at me warmly.

…Films and novels set in mental hospitals occasionally portray close friendships, but researchers either cannot or will not recognise their existence. Back in the 1950s an academic fashion arose for quantifying personal relationships through a method known as “sociometry” or “companion measures”. Researchers observed people whose interactions were enumerated and then displayed on graphs known as “sociograms”. The method was widely applied to asylum inmates, including by the team of social scientists hired to study Friern. One of the researchers undertook a numerical analysis of patients” conversations (an “intimacy index”). At no point did either researcher ask any of the patients how they actually felt about the other people there.

I do not want to romanticise this world. Hanging out with disturbed people can be awful. I know my friends at Friern often found me very poor company. I went several times to the patients’ coffee bar (perhaps I was one of the specimens studied by the sociologists) and found it almost unbearable. Magda, however, felt differently. She knew many people there and enjoyed catching up with them. She was especially pleased one afternoon to encounter a woman who had been a bookseller until she fell prey to chronic alcoholism. To me the woman looked like a mumbling wreck, but Magda chatted with her for a long time while I sulked in a corner. Afterwards Magda scolded me. “She is a smart, interesting person, Barbara – you need to talk to people before you judge them.” I had been told this before, in very different contexts, but this time the criticism took.

Today people with ongoing mental health problems have few dedicated social venues. The day hospitals and day centres have mostly closed, usually in the face of anguished protest. When I ask mental health managers about this, I am repeatedly told that it is not good for service users to spend all their time with other service users; they should mingle with healthy people in the “community”.

It is pointed out to me that mental illness is often episodic; that many people are unwell only intermittently and what they really need is help in utilising their capabilities during their well times instead of becoming “career mental patients” consigned to psychiatric ghettoes. There is real force to this argument. But it is also a convenient argument, legitimising yet more swingeing cuts in mental-health budgets, and one that leaves untouched the miserable isolation of many mentally ill people in the UK today, sitting alone in their flats with only a television to keep them company.

It is pointed out to me that mental illness is often episodic; that many people are unwell only intermittently and what they really need is help in utilising their capabilities during their well times instead of becoming “career mental patients” consigned to psychiatric ghettoes. There is real force to this argument. But it is also a convenient argument, legitimising yet more swingeing cuts in mental-health budgets, and one that leaves untouched the miserable isolation of many mentally ill people in the UK today, sitting alone in their flats with only a television to keep them company.

Magda suffered terribly from black depression yet nearly always she would pull herself together to be with me. Usually I did the same for her. The obligations of friendship trumped madness – and this in itself could be a form of healing.

__________

Return to: Five Hundred Years of Friendship at the History of Emotions Blog