Emma Townshend is a writer and journalist, and the author of Darwin’s Dogs: How Darwin’s Pets Helped Form a World-Changing Theory of Evolution. In this post for the History of Emotions blog she writes about new research she has been doing into the representation of dogs in nineteenth-century fiction, arising from her contribution to Episode 8 of ‘Five Hundred Years of Friendship’.

Emma Townshend is a writer and journalist, and the author of Darwin’s Dogs: How Darwin’s Pets Helped Form a World-Changing Theory of Evolution. In this post for the History of Emotions blog she writes about new research she has been doing into the representation of dogs in nineteenth-century fiction, arising from her contribution to Episode 8 of ‘Five Hundred Years of Friendship’.

__________

“A dog’s devotion is unquestioning, undemanding and undiminishing… If living without the lunatic companionship of dogs is proof of sanity, please God, let me be mad.”

Brian Sewell, Sleeping with Dogs (2013)

It won’t come as any surprise to dog-lovers in the early years of the twenty-first century, that there are still people like Brian Sewell in the world, much preferring to share his bed with his dogs than with another human. Charles Darwin was not quite such a Sewell-ite soft touch as a pet-owner – his most indulgent trait seems to have been throwing his dogs bits of biscuit between meals – but his letters nevertheless reveal a tender sense of love for his canine companions.

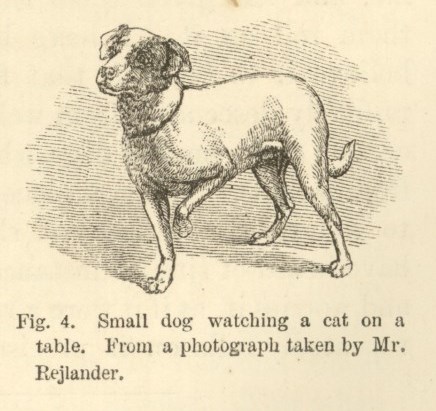

Darwin’s dog-owning began with Spark, which he owned as a teenager. “I hope you will send me many more nice affecting letters about dear little black nose,” he wrote in one scrawled message home from university. It progressed through Shelah, Czar, hunting dogs Sappho, Fan and Dash, Pincher, Nina, and family pets Bob, Bran; adoptive animals Tony, Quiz, Tartar, Pepper and Butterton; and the last dog of his life, Polly, whom his daughters felt was the most beloved of all, and who appears in the illustrations to his 1872 book, on The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals.

Darwin’s interest in dogs focused on the question of how much the ‘higher animals’ were really like us. The problem was an important one: it held the key, Darwin thought, to establishing that all life on earth evolved from one distant, common ancestor. In argument, Darwin’s opponents often evoked ‘unique’ human qualities such as altruism, loyalty and love, to ‘prove’ that Homo sapiens was on an entirely different level of creation to all other animals on earth. Darwin argued that a deeper examination of zoological behaviour would find all those ‘noble’ qualities in animals themselves. That we were all on a continuum.

The mid-nineteenth century saw a massive shift in general in attitudes towards animals. It marks the foundation of the first animal welfare organisations, such as the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (later acquiring ‘Royal’ status to become the RSPCA) in 1824, and the passing soon afterwards of the first legislation to protect animals. But it also witnessed another interesting change, which I found out more about whilst researching for my contribution to Episode 8 of ‘Five Hundred Years of Friendship’. This is the increasing interest of fiction writers in the mental world of animals, and in particular, dogs.

When I first began to look at dogs as characters in fiction, I thought it might be a short list. Certainly White Fang & Call of the Wild, by Jack London, about working dogs in the American west; and Virginia Woolf’s biography of Elizabeth Barrett Browning from the point of view of her cocker spaniel, Flush. In fact, since I’ve been researching, the list grows longer and longer, and I haven’t stopped finding examples.

Of course, it isn’t an exclusively modern phenomenon to make a dog a character. Think of Homer, where Odysseus’s dog is the sole friend on Ithaca to recognise delightedly the returning, war-grizzled hero. Bruce Thomas Boehrer has argued in his recent book, Animal Characters, Nonhuman Beings in Early Modern Literature, that pre-modern writing contained plenty of thinking and even talking animals, appearing in beast fables, travel writing, and supernatural tales (you can read more about Bruce’s book in this article). But by the 1600s, this view was seen as out-of-date and whimsical; Shakespeare and Cervantes even made fun of it. Then Descartes put the final boot in by proposing a philosophical view of the world that ruled out animals being anything other than complicated machines.

It was the mid-nineteenth century before animals returned as central characters to story. At the exact moment when Darwin was looking at his own dogs (and ascribing to them intention, moral scruples, altruism, planning, memory, and love) some of Europe’s greatest writers were doing the same. Turgenev in 1854 published ‘Mumu’, a story of friendship between a poor man and a dog, so moving that the RSPCA sent a wreath to the author’s grave when he died.

Tolstoy, in Anna Karenina (published 1873-7) has a whole chapter – where Levin goes hunting in the Russian countryside – written from the point of view of Laska, Levin’s dog.

‘Well, if that’s what he wishes, I’ll do it, but I can’t answer for myself now,’ she thought, and darted forward as fast as her legs would carry her between the thick bushes. She scented nothing now; she could only see and hear, without understanding anything.

Or there is Chekhov, in the long story Kashtanka, published first in 1887, written entirely from the point of view of a dog who runs away to the circus, eventually returning to its owner.

There are also more conventionally telling attempts by writers to capture friendly human relationships with dogs. Thomas Mann, Nobel Prize winner, narrated the tale of Bashan, his own dog, in great detail; so much detail, in fact, that we learn more about Thomas Mann’s egocentric delight in his dog’s devotion than we do about the dog. Kafka in contrast wrote a tale, left unfinished at his death, of a bachelor called Blumenfeld who is dithering about whether to get a dog or not. Blumenfeld pines for the company but lists all the impracticalities of dog ownership, in a way that leaves us completely pitying him, and possibly also the tale’s author. Kipling and PG Wodehouse, in a third strand, tell comic stories entirely from the point of view of mischievous dogs, depicted with enormous fictional skill.

It seemed to me as I read these stories, that these great writers were doing exactly the same thing as Darwin. They were questioning the borders of animal and human; they were asking whether animals think, love and dream; and they were working out how to set their conclusions down on paper. Tolstoy wrote fiction; Darwin wrote scientific prose, but in the end, both men believed in dogs as beings with many similarities to ourselves, worth paying attention to and setting down in print. We are all cut from the same animal pattern, they argued; we all love, we all dream, we all fear, we all plan, we all act with kindness, compassion and grace, on occasion. And in extending this compassionate gaze to animals, we become friends with them, in a slightly strange way, but nonetheless, we do. Which leaves Brian Sewell slightly less bonkers than he might first appear.

___________

Return to: Five Hundred Years of Friendship at the History of Emotions Blog