Dr Helen Rogers is Reader in Nineteenth-Century Studies at Liverpool John Moores University. With her undergraduate students she has created Writing Lives: A Collaborative Research Project on Working-Class Autobiography. This blog post, written by Helen with Cleo Chalk, Steve Clark, John England and Victoria Hoffman, draws on the riches of working-class memoirs to explore friendship and improvement in the nineteenth century – the central theme of the second week of episodes of ‘Five Hundred Years of Friendship‘.

Dr Helen Rogers is Reader in Nineteenth-Century Studies at Liverpool John Moores University. With her undergraduate students she has created Writing Lives: A Collaborative Research Project on Working-Class Autobiography. This blog post, written by Helen with Cleo Chalk, Steve Clark, John England and Victoria Hoffman, draws on the riches of working-class memoirs to explore friendship and improvement in the nineteenth century – the central theme of the second week of episodes of ‘Five Hundred Years of Friendship‘.

__________

Friendships are among our fiercest and most enduring relationships. They can be fraught and fleeting too. We so easily take them for granted, putting families and partners first. Historians have been similarly neglectful, mentioning friendship only in passing while studying family, household and sexual relationships, or networks around work, religion and politics. Personal memories reveal, however, that friendship is integral to all these aspects of social life and to our deeply-felt sense of self, both personal and collective.

While researching autobiographies by working-class people for the Writing Lives website, we decided to look at what friendship meant to our authors and what these relationships can tell us about working-class culture in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[1]

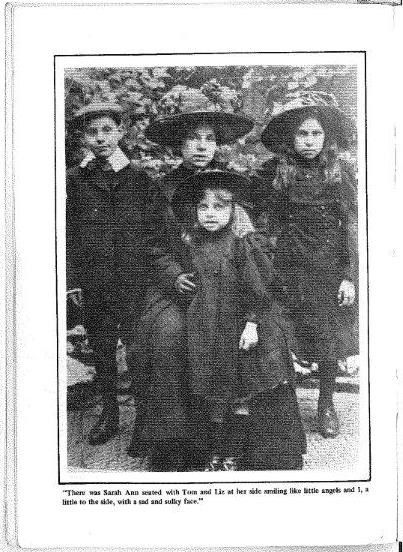

Friendships helped many authors establish their identity outside the family. Friends could be especially important to children who experienced bereavement. Lottie Martin, born 1899, lost her mother at ten and left school at thirteen to look after her siblings. Her family were ‘close and good-humoured’ but ‘Withdrawn and shy, causing many of our associates to think we were “stuck up”’.[2] Meeting with former school friends gave Lottie freedom from domestic responsibility and from her family’s claustrophobic respectability.

From Paula Hill Never Let Anyone Draw the Blinds by Lottie Martin (Nottingham: 125 Bramcote Lane, 1985)

With her girlfriends, Lottie discovered the courting rituals of walking out. About a dozen girls would meet with boys from the neighbouring village and ‘pair off to stroll along the river side or walk over the fields’. This was a safe and companionable way of encountering the other sex: ‘Everything was so lovely and innocent’.

Friendships could provoke disapproval and family tension, as Lottie found to her cost. Her ‘favourite’ was Flo:

a happy carefree girl always smiling and full of fun and jokes. The boys loved her and because she would do all those things I longed to do, but dare not I loved her too. But oh the trouble she would get me into.

Free-and-easy girls like Flo were looked down upon by ‘respectable’ families. In defying her elder sister, who tried to stop the friendship, Lottie struck out for her own independence and alternative values.

Respectability could make and break friendships, as Jack Goring, born 1861, discovered. In his teens, Jack grabbed the opportunity to learn history, drawing and elocution at the Youth Institute. This meant giving up the variety shows he used to watch with an old friend who did not share his passion for ‘improvement’. Faced with a choice, Jack ‘let him go’ in favour of the Institute.[3] Later generations of scholarship boys and girls often lost the friends they ‘left behind’ when they went to grammar school and university, yet felt uneasy among companions from a different class. Friendships can be the first casualties of social mobility.

For the Victorian working classes, self-education and ‘mutual improvement’ brought together like-minded people and forged networks which sustained people through their working life. At the Youth Institute, Jack made life-long friends who later moved with him in freethinking, radical and bohemian circles. They helped him establish his business in advertising and encouraged him as a writer. Sixty years on, Jack described four surviving members of the Institute as ‘my very dear friends of whom I have had good cause for affectionate and lasting remembrance.’

Men often wrote significantly more about friendships than their relationships with wives and children. Their experience as husbands and fathers was a ‘personal’ matter that did not belong in their memoir. By contrast, writing about their intellectual companions, acquaintances at work, and political associates all helped to illustrate the men they had become.[4]

Born in 1880, Harry West revealed little of his marriage but showed how friendships supported his intellectual development when he left school because of poverty. When working in an office as a young man, his workmate Perry Mayer passed on his Grammar School learning. Yet, Harry liked him precisely because ‘He was a character entirely opposite to myself. He was a rugby player, a boxer, hot-tempered impulsive and hated office life.’ Accepting the nickname ‘Westy’, Harry called his friend ‘Mary’ in return, ‘although there was nothing feminine about him’.[5]

In their pet names, ‘Westy’ and ‘Mary’ jovially adopted a marital persona for their friendship. Historians have noted how friends in the Victorian period, especially women, often wrote to and about each other using the language of romantic love. Some have speculated that such ‘romantic friendships’ expressed same-sex desire.[6] Perhaps these relationships also suggest a culture more at ease with intimate friendship than subsequent generations. As policing of homosexuality increased and homophobia became more pronounced, same-sex friendships came under closer scrutiny. It’s striking that in the 1950s, when writing his memoir, Harry felt the need to emphasise there was nothing effeminate about his friend or untoward in their relationship.

While writing sympathetically about homosexuals he knew in the army, Syd Metcalfe, born 1910, exhibited this growing self-consciousness and nervousness around same-sex friendships when trying to describe closeness between heterosexual men. Losing contact with his father in childhood and then estranged from his flighty mother, Syd found security and companionship when he joined the forces in the 1930s. There he became ‘inseparable’ from his friend Jack:

We became known as ‘The Twins’ and I can remember I actually missed him if he weren’t there. This is a relationship, perfectly decent, akin to the love of a man for a woman. There is in it an affinity that makes one almost part of the other. Certainly there is a mental need of one for the other. . . If one carried this comparison further I suppose it is a form of love.

Let us forget for a moment today’s obsession with everything having a sexual basis, for this oneness that Jack and I felt in each other’s company had nothing to do with sex. And I’m equally sure that the early, young love that most of us have experienced at some time or another for a girl also has no foundation in sex. Can’t you remember loving a girl beyond that?[7]

Despite their closeness, when Syd left the army after eight years, the two men lost contact.

While friendships can outlive partnerships, be stronger than family relationships, last almost a lifetime, they are also vulnerable to changing circumstances and other loyalties and obligations. What breaks them may tell us as much about the history of friendship as what binds them.

__________

Follow Writing Lives on Twitter: @Writing__Lives

Follow Helen Rogers on Twitter: @helenrogers19c

Visit ‘Writing Lives’: A collaborative research project on working-class autobiography

Return to: Five Hundred Years of Friendship at the History of Emotions Blog

[1] Writing Lives: A Collaborative Research Project on Working-Class Autobiography is created by Helen Rogers and undergraduate students studying English at Liverpool John Moores University. We are working with the John Burnett Collection of Working Class Autobiography (Brunel University Library) and hope the memoirs will be available online in the near future.

[2] Paula Hill Never Let Anyone Draw the Blinds by Lottie Martin (Nottingham: 125 Bramcote Lane, 1985), ch. 2; Lottie Barker [nee Martin], ‘My Life as I Remember It, 1899-1920’, (unpublished TS, Brunel University Library, 2:37); John England, Lottie Martin, 2014.

[3] Jack Goring, Autobiographical notes, (MS, BruneI University Library, 1:274); Victoria Hoffman, Jack Goring, 2014.

[4] David Vincent, Bread, Knowledge and Freedom: A Study of Nineteenth-Century Working-Class Autobiography (London: Methuen, 1981).

[5] Harry Alfred West, ‘The Autobiography of Harry Alfred West. Facts and Comments’ (unpublished ms, Brunel University Library, 1:745), p. 30. Cleo Chalk, Harry Alfred West, 2014.

[6] Lillian Faderman, Surpassing the Love of Men: Romantic Friendship and Love Between Women from the Renaissance to the Present (New York: William Morrow & Company, 1981).

[7] Syd Metcalfe, ‘One Speck of Humanity’ (TS, Brunel University Library, 2:526), p. 138; Syd Clark, One Speck of Humanity (Charnwood, 2000); Steve Clark, Syd Metcalfe, 2014.