Dr Thomas Dixon is Director of the Centre for the History of the Emotions at Queen Mary, University of London. This blog post is the text of a talk he gave at the ‘Vessels of Tears’ event, curated by Leverhulme Artist in Residence Clare Whistler on 7 May 2014. He has previously presented a BBC Radio 3 feature on the cultural history of weeping.

Dr Thomas Dixon is Director of the Centre for the History of the Emotions at Queen Mary, University of London. This blog post is the text of a talk he gave at the ‘Vessels of Tears’ event, curated by Leverhulme Artist in Residence Clare Whistler on 7 May 2014. He has previously presented a BBC Radio 3 feature on the cultural history of weeping.

Clare Whistler’s residency at the Queen Mary Centre for the History of the Emotions was timed to coincide with the completion of my current book project – Weeping Britannia: Portrait of a Nation in Tears.

In these few comments this evening – offered in between two of the gripping and mesmerizing ‘Compass Me’ films – I will think briefly about three aspects of tears – vision, connection, and pain.

While I am working on a portrait of a nation in tears, Clare has, during her residency here, made a portrait of a research centre in tears, even a university in tears – as well as a portrait of water in the natural world – rain, streams, and glaciers.

And it is this duality that I think is so fascinating when it comes to tears as subjects for historical research. A tear is an intellectual thing – as William Blake once wrote. It is a liquid thought. But a tear is also a natural thing – part of the worlds of physiology – of human meteorology – a secretion or a precipitation of the mind.

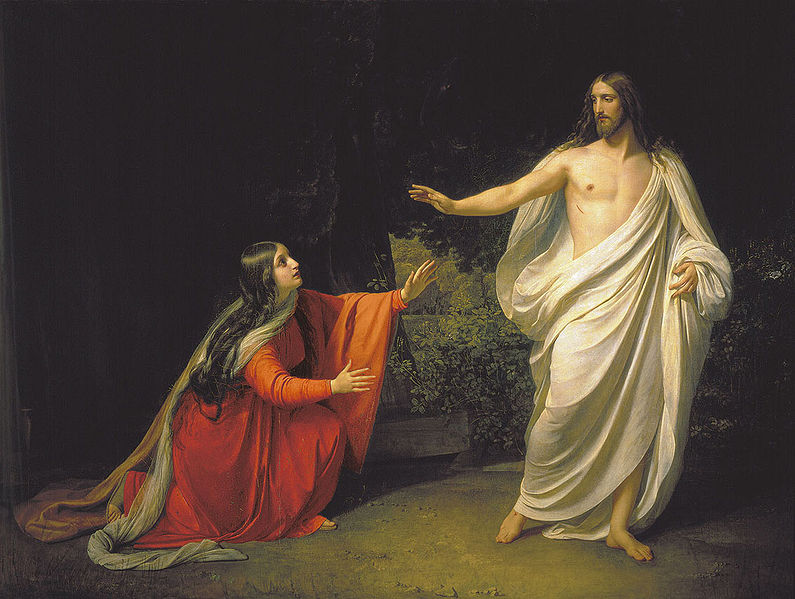

Watching the ‘Compass Me’ films, we have the experience of seeing the body through water – ancient, historic, water, once a glacier – now part of an extraordinary library. Looking through water is like seeing through tears. Is it distorting or clarifying?John Donne once described tears as ‘false spectacles’. According to the gospel of John, Mary stands outside the empty tomb of Jesus weeping, and mistakes the risen Christ for the gardener. Did her tears of grief obscure her vision? Or did they in fact make possible the vision that led to her recognition of her master a moment later?

After the weeping Mary recognizes Jesus, in John’s gospel, he tells her not to touch him – a scene depicted here by Alexander Ivanov.

Seeing Through Tears is the title of one of the most interesting psychological studies of the meaning of weeping. Its author – the psychotherapist Judith Kay Nelson – interprets tears through attachment theory. Nelson’s main point is that tears are not best thought of as expressions of individual emotion, but rather as part of a social system of attachment and care-giving. For her weeping is never a one-person activity – it is about connection. ‘Only connect’, said E. M. Forster. Personal relations are everything. And it is often the moment of connection that brings tears.

But I’d suggest that we take that idea of connection further. It can be a moment of intellectual insight or indeed self-realisation that produces the tear of connection. We can connect with our selves – our past selves, submerged selves, true selves. And that can produce tears. I even think that a moment of aesthetic connection – or a realisation of the harmony between two previously unconnected thoughts or images can be tear-inducing. Only connect.

For me such a connection came watching ‘Compass Me’. Clare’s movements – suggestive of pain – along with her enlarged and sometimes disappearing hands, brought to my mind the story of Shakespeare’s first tragedy, Titus Andronicus.

As well as being a play of astonishing violence, pain, passion and madness, it is a study of tears and loss – the loss of bowels, of heads, of hands, and of life.

I found myself thinking about Titus’s daughter Lavinia – raped and mutilated – her tongue cut out, her hands hewn off – and the madness of grief her suffering caused in her father.

For Shakespeare, as for René Descartes in his treatise on the passions, as for Robert Burton in his Anatomy of Melancholy, and as for George Herbert in his religious poetry,tears are part of a connected human and natural world – a world of motion and emotion: a system of humours and fluids.

For Shakespeare, as for René Descartes in his treatise on the passions, as for Robert Burton in his Anatomy of Melancholy, and as for George Herbert in his religious poetry,tears are part of a connected human and natural world – a world of motion and emotion: a system of humours and fluids.

In Titus Andronicus, Shakespeare identifies tears with all the seasons and all the waterworks of nature: streams, rivers, and oceans; showers, storms and life-giving rain. The Andronicus weather is foggy, damp, and overcast. (And it’s appropriate we are in the Fogg building this evening.)

Lavinia and Titus at different points refer to their ‘tributary tears’ of mourning, alluding simultaneously to tributes to the dead and to natural rivulets – an image suggesting streams feeding into swelling, larger rivers of collective woe.

As George Herbert wrote:

O Who will give me tears? Come all ye springs,

Dwell in my head & eyes: come clouds, & rain:

My grief hath need of all the wat’ry things,

That nature hath produc’d.

Steams flow into rivers, rivers into the ocean.

Having poured out his woes for the mangled Lavinia, Titus is persuaded by the evil moor Aaron to cut off his own hand as a ransom for the safe return of his sons.

At this desperate, painful moment, Titus depicts his own tears as elemental forces, describing himself as the sea and the earth; Lavinia as the sky, or ‘welkin’, and the wind.

I am the sea; hark, how her sighs do blow!

She is the weeping welkin, I the earth:

Then must my sea be moved with her sighs;

Then must my earth with her continual tears

Become a deluge, overflow’d and drown’d;

For why my bowels cannot hide her woes,

But like a drunkard must I vomit them.

This speech – like the ‘Compass Me’ films – is one of those moments in my research over the past five years that have gripped me and seemed to distil and represent something that captures what it is about tears that makes them such a powerful conduit between the human mind and the natural world.

A tear is an intellectual thing. But it is also natural, watery, meteorological, oceanic.

‘I am the sea’.

In the next scene, Titus is confronted with the two heads of his sons – and his own hand – contemptuously returned to him by a messenger. His brother, Marcus, who has been seeking to moderate Titus’s passions, now gives him permission to rage in grief, but Titus instead lets out a horrible laugh: ‘Ha, ha, ha!’

Marcus protests: ‘Why dost thou laugh? It fits not with this hour.’ Titus replies: ‘Why? I have not another tear to shed.’

Ultimately, Titus kills not only his enemies, but also Lavinia, ‘her for whom my tears have made me blind’

It is when the weeping stops, rather than when it starts, that vision is blinded, that reason departs – and that the stream of life becomes polluted by death. The message of Titus Andronicus is captured, in fact, in a line from one of the ‘Tear Bottle’ poems made by Clare from her interviews during her residency: “it is tragic to lose the ability to cry.”

Read more about ‘Weather, tears, and waterways’.

Read about and listen to all of the related podcasts.