Dr. Mary C. Flannery is maître assistante (lecturer) in medieval English at the University of Lausanne. She is the author of John Lydgate and the Poetics of Fame, and is currently completing a book on shame in medieval English literature. In June 2015, she organized a two-day workshop at the University of Lausanne (UNIL) on ‘Emotion & Medieval Media’ (programme available here). In this post, Mary reflects on the findings and the format of the event…

‘FORT EN EMOTIONS!’ in Lausanne Gare. Photo by Mary Flannery.

Upon arrival in Lausanne this summer, you might see the billboard advertisement above, which declares the nearby destination of Mont-Fort to be ‘Fort en émotions!’. Emotions seem to be ubiquitous in Swiss advertisements these days. Advertising for the 2015 Tour de Suisse included the catchphrase ‘Experience emotions’. Neuchâtel’s Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle is currently running a temporary exhibition on emotions. Posters throughout Geneva Airport invite travellers to make the most of ‘EMOT!ONS Airport Shopping’.

This flood of emotion-laden Swiss advertising coincides with an ongoing project based at the University of Lausanne (UNIL) on ‘Emotion & Medieval Media’ (EMMe), which led to a workshop on the subject on 19 and 20 June. Funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation and UNIL, EMMe included participants drawn from the fields of manuscript studies, literature (Old Norse, and Old and Middle English), linguistics, drama, art history, and musicology. Participants were given a list of some suggested reading before the workshop, as well as a handful of articles on different approaches to the history of emotions; these were intended to provide the group with a common grounding in terminology and recent debates in the field of emotion studies in order to facilitate exchange between the different disciplinary perspectives represented in the workshop.

The two days of the EMMe workshop comprised similar line-ups of different session formats. Each day began with a session of three twenty-minute panel papers, followed by discussion. These sessions enabled presenters to receive feedback on their work-in-progress. After a short break, workshop participants returned for a session of ‘guided analyses’, in which scholars from different disciplinary backgrounds led discussion of selected texts and artefacts (a passage from a literary text, a short play, carved ivories, and a liturgical vestment). On both days, lunch was followed by a performance: a concert of medieval music on the first day, and a performance of the Historie van Jan van Beverley on the second day. These performances concluded with group discussion, in which both audience members and performers participated. This variety of session formats encouraged lively discussion, enabled participants to experiment with methodologies and media from different disciplines, and gave everyone the opportunity to experience medieval music and drama either as performers or as audience members. Each day concluded with a different wrap-up session: a roundtable and discussion on the first day, and a concluding keynote on the second day (in which Professor Rita Copeland had the unenviable task of responding to both days of the workshop!). All sessions were live-tweeted using the hashtag ‘#emomedia’.

The first aim of the EMMe workshop was to consider how medieval theories of emotion and cognition informed the creation and reception of different medieval media. The workshop’s second objective was to consider how attention to different media forms could inform the study of medieval emotion. As the organiser of the event, I had anticipated that both of these questions would drive the majority of workshop discussion. What actually transpired, however, was rather different.

Although discussion occasionally touched on the relationship between medieval theories of emotion and different media, we more frequently talked about the kinds of emotional impact different medieval media could have, and how creators, consumers, and scholars of various media engaged with (or denied the existence of) these emotions. Daniel DiCenso’s opening paper noted that emotion is something of a taboo subject in Gregorian chant scholarship; his enumeration of the arguments he has encountered against the study of emotions in plainchant made clear that, if the precise role of the arts in the history of emotions is unclear, emotions can also be uneasy subjects in arts research. Through their led discussion of A Talkyng of the Love of God, Camille Marshall and Diana Denissen drew our attention to the directive role that medieval texts could play in inspiring religious devotion in their readers. Denis Renevey demonstrated how a medieval lyric used the name of Jesus as a starting point for the practice of affective piety. Catherine Yvard showed us how carved ivory combs might have been used to inspire or reflect love between an affianced couple in medieval Europe. Michaela Zöschg’s guided analysis of the Syon Cope led participants to consider the role of emotion in the production, the wearing, and the viewing of the vestment (Michaela brought along paper cut-outs of the cope for us to model on water bottles, in order to have a better sense of how it would have looked while worn). Charlotte Steenbrugge argued that the performed emotions in Middle English Abraham and Isaac plays, as well as audience responses to them, encouraged a surprisingly critical response to the Biblical story. And as the presentations of Marcel Elias and Lucie Kaempfer made clear, different literary genres were accompanied by different expectations related to emotional content, some of which individual texts might conform to and some of which they might subvert.

Paper cut-out of the Syon Cope, provided by Michaela Zöschg for the EMMe workshop. Photo by Mary Flannery.

Similarly, the question of how research on various media might contribute to the history of medieval emotion raised the related issue of methodology. Each medium posed different methodological challenges and opportunities. Amy Brown tested out word searches in her presentation on ‘friendzoning’ in the Stanzaic Morte Arthur, while Anita Auer married quantitative with qualitative analysis in her proposal for a corpus-linguistic approach to medieval emotions research. Tamara Haddad, who both researches and stages medieval and early modern drama, spoke about the challenges and questions raised by site-specific performance. A scholar working in manuscript studies, Marleen Cré, pointed out the complications one encounters when looking for evidence of emotional engagement in the traces left by manuscript readers. And Sarah Baccianti and Sarah Brazil explored how different literary tropes might be used to convey or cultivate emotion, focusing respectively on somatic descriptors and on metaphors. The range of presentation formats enabled us not only to absorb and comment on each other’s scholarship, but also to be guided through analytical processes in each other’s disciplines and to participate actively in investigating media with which we might not all, as individuals, have had considerable previous experience.

The two performances featured in the workshop enabled us to witness medieval music and drama in action. Singers, actors, musicians, directors, and audience members shared their perspectives on the role of emotion in performance. Both the concert of music performed by Shauna Beesley, Rachael Beesley, and Minna Harlan and the performance of the Historie van Jan van Beverley staged by Elisabeth Dutton and Tamara Haddad prompted us to ask whose emotions were involved, and how. As Shauna noted, the physical experience of singing the trills in Jacopo da Bologna’s ‘Non al suo amante’ gives the singer a shivery sensation that might be likened both to the feeling of the chilly waters described by the lyrics and to the amorous ‘chill’ the song’s narrator claims to experience….

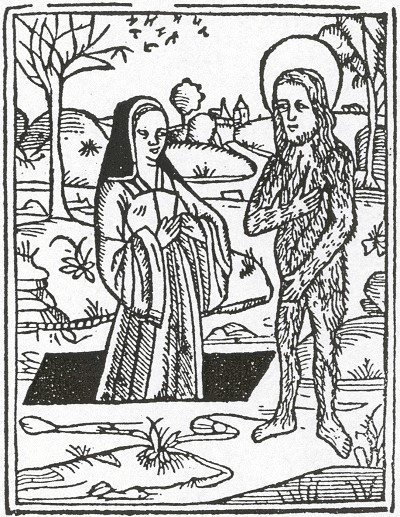

Elisabeth pointed out the importance of looking for implicit stage directions regarding what kinds of emotional gestures might be employed at particular moments within a medieval play (a particularly important point in relation to the creative decision she and Tamara made to base a number of the actors’ gestures on the woodcut images accompanying John of Beverley’s story, which may or may not have been a play after all).

Historie van Jan van Beverley (Brussels: Thomas van der Noot, around 1512) Picture credit: Digital Library of Dutch Literature (DBNL).

Watch a recording of the performance:

From such a varied group of topics, presentations, and performances, it might seem impossible to pull together any kind of response that was at once coherent, critical, and constructive. Yet this is precisely what Rita Copeland proceeded to do at the end of the second day of EMMe. In an outstanding concluding keynote, Rita responded to each of the presentations and performances individually while also touching on the key themes that had dominated workshop discussion. Crucially, she noted that the workshop’s presentations and performances had tried to shift away from an emphasis on ‘extra-textual reality’ (an emphasis that researchers of emotion in the arts have perceived as characteristic of most historical approaches to emotions) and towards approaches that take the artistic forms that engage with emotion as the objects of their inquiry.

It is impossible to do justice to Rita’s keynote here (even the recording doesn’t seem to capture how galvanizing it was), and the brief mentions of the presentations and performances that I have provided above can only provide a sketch of the rich variety of subjects we covered in the EMMe workshop. But I find myself returning to a question that Rita mentioned had been at the back of her mind throughout the event: were we talking about the history of emotions, or about emotions in the history of various disciplines? Or both?

These questions lie behind the biggest change that I would make to the workshop, if I could do it all over again: I would make sure to include historians among our presenters and audience members (as Amy Brown noted on the Australian Medievalists blog, this was one notable gap among the disciplines represented). The EMMe workshop was a wonderful opportunity for arts scholars to exchange ideas and to draw on each other’s methodologies and areas of specialisation. But bringing our work into more direct conversation with the work of historians would get us much closer to incorporating the arts more fully into the history of emotions.

As a literary scholar interested in the history of emotions, one of the questions that I continually grapple with is that of how the study of literature and other arts can contribute to the study of past emotions. To what extent can we employ art as evidence in this history, and what is it evidence of? In the case of my own discipline, I have become increasingly convinced that the answers must be found in the ‘literariness’ of literature, in its forms, genres, and tropes. And indeed, instead of making literature and other arts transparent—aiming to look through them to find historical truth—I think we are finding ways of investigating emotion by looking at art, at its surfaces and forms. But the only way that this will happen successfully is via real exchange, not just among the arts, but between those working in the arts and those working in history, the life sciences, and the social sciences.