Dr Sally Holloway and Jane Mackelworth report on the third meeting of their community book group, exploring love and its history through literature…

The third meeting of our book group focused on one of the lesser-known Gothic writers of the early nineteenth century, Charlotte Dacre (c. 1772-1825), and her second novel Zofloya, or The Moor (1806). Born Charlotte King, Dacre was the daughter of the moneylender John ‘Jew’ King (c. 1753-1824), who famously engaged in an adulterous affair with the actress Mary Robinson in 1773. Dacre’s writing career began with the publication of several poems in the Morning Post, before she moved on to write four novels, of which the other three were: Confessions of the Nun of St. Omer (1805), The Libertine (1807) and The Passions (1811).

Until recent years, Zofloya, and Dacre’s work more generally, has been relatively unknown both in scholarship, and also by the reading public. None of our members had previously heard of the novel or its author. Kim Michasiw argues that this lack of awareness is in part because the book’s heroine is ‘a mother-hating triple murderess who dreams of sexual congress with a demon of colour.’[1] Yet this contrasts with Dacre’s relative success at the time.[2]

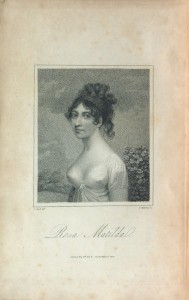

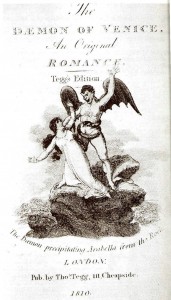

Zofloya is a novel in the gothic tradition, begun by Horace Walpole’s Castle of Otranto (1764), and developed by Matthew Lewis’ The Monk (1796), and Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) and The Italian (1797), among others. Dacre was clearly influenced by Lewis, whose visceral and shocking style was designed to invoke horror and disgust.[3] One of her pseudonyms was Rosa Matilda, which is directly taken from the name of the demon lover in The Monk, known alternately as Rosita or Matilda. Scholars have argued that Dacre deliberately placed her novel in this male tradition of ‘pornographic and sensationalist literature’, seeking to trump The Monk for ‘salaciousness and horror.’[4] Yet Dacre’s work was also unique in its portrayal of gender and race, and explicit exploration of women’s sexual desire and subjectivity. This was unprecedented in both gothic literature, and wider literature of the time. These themes were discussed at length by our group.

The novel (spoiler alert!) tells the story of the Loredani family, primarily the daughter Victoria. We follow Victoria as she leaves home and marries Count Berenza, who she quickly becomes unhappy with, largely because he is unable to satisfy her sexually. She then falls in love with his brother Henrique and sets out to make Henrique return her love, with the help of Zofloya, a Moor, who is Berenza’s servant. Aided by Zofloya, Victoria poisons her husband, then takes Henrique’s fiancée Lilla to the mountains and holds her captive. Victoria then gives a love potion to Henrique and consummates her relationship with him. Shortly after this he commits suicide, and Victoria kills Lilla before partnering up with Zofloya in some nearby caves. At the end, readers learn that Zofloya is the Devil, who sends Victoria to her death in the mountains.

Our members found Victoria a fascinating anti-heroine, an observation also made in scholarship, with Emma Clery referring to her as ‘a remarkable creation’ with ‘no concessions … made to the stereotype of the sentimental heroine.’[5] We particularly revelled in her juxtaposition against Lilla, who most of the group found to be a deliberately dull character, representing a passive and helpless feminine stereotype, much more typical of women throughout Gothic novels, who find themselves in need of rescue. Diane Long Hoeveler has described Lilla as emblematic of the new feminine type emerging at the start of the nineteenth century, a gender ideal which became strengthened during the nineteenth century and featured in later Romantic poetry.[6] Victoria is a refreshing contrast, able to escape brief imprisonment through her own resources, and later capturing, imprisoning and killing Lilla. Victoria’s emotional state is marked by pride, envy, hatred and revenge, compared to the usual emotions felt by gothic heroines, such as love, fear, joy and grief.[7] The group relished the way that Victoria was a transgressive, even evil, character, finding her wickedness refreshing.

We admired Victoria because she followed her own desires, particularly in her pursuit of men.[8] The novel therefore represented women’s sexual subjectivity in a new way, with Clery suggesting that ‘Victoria’s passions are unlike anything else in the women’s Gothic writing of the period.’[9] It is also interesting to consider the impact on readers at the time. Mellor argues that the text would have ‘enabled Dacre’s readers to explore a far wider range of sexual options…than did the other writing of her day.’[10] The group also debated what Dacre’s overarching message, or moral framework, might be concerning women seeking autonomy, particularly sexual autonomy. Victoria ultimately meets her end through following her desires, and this in itself is seen as being the fault of her mother previously doing the same. The novel opens with Victoria’s mother being seduced and deserting her family. It is the mother’s pursuit of her own desires and the impact on her family honour, which is clearly indicated in the novel as the cause of Victoria’s downfall, and that of her brother who falls in with a gang of bandits. On the whole, the group concluded that Dacre was giving a negative impression of women who indulged their lust. Our debate concerning Dacre’s overarching message mirrors that in the wider historiography. For example, Nayar argues that the novel suggests that a woman pursuing her own sexual agency threatens English domesticity, the family and ultimately the boundaries of England.[11] Pramrod Nayar suggests that Dacre is therefore ambivalent about the issue of women’s agency and that it is unclear where her loyalties lay.[12] However, Clery suggests that Dacre was simply doing ‘cursory moralizing’ noting that she went on to create several other female monsters in her work.[13] And so it is possible that the inclusion of an overarching Christian message allowed her to get away with the themes that she portrays in the novel.

Our readers were intrigued by Dacre’s controversial portrayal of a white woman desiring a black man. Victoria’s partnership, and particularly her longing and desire for Zofloya, a black man, was an unusual and unprecedented representation in literature at this time. Anne Mellor has described this as perhaps ‘the most taboo of all human sexual desires in Romantic-era England.’[14] The novel was published the year before the slave trade (not slavery itself) was abolished by parliament. Dacre’s choice of pairing between Victoria and Zofloya can therefore be seen as a bold move, which challenged wider social norms.[15] Discussions around the abolition of slavery had opened up the possibility of interracial relationships, yet where these had been represented in literature beforehand this was almost exclusively through the eyes of the male and his desire; whether the white man desiring the black woman or the black man desiring the white woman.[16]

We discussed Dacre’s motivations for this and where her political sensibilities may have lain, although were unable to reach consensus. Scholars have also debated this point. Long Hoeveler highlights the ‘racist’ and ‘xenophobic’ themes of the novel, arguing that it should be seen as part of a wider Colonial project.[17] For example, the novel can be read as highlighting the perceived threat to England from outsiders through the devastation caused by Zofloya. However, as Nayar asserts, the real threat to English domesticity in the novel comes not from Zofloya but from both Victoria, and her mother, because they followed their own desires. And Nayar is keen to highlight that Victoria is not merely seduced by the Moor, rather she is following her own ‘quest for sexual agency.’[18]

The black character’s representation of the Devil also seems to highlight the racist context in which the novel was written, with Dacre once more tapping into wider concerns that Englishness was being lost or threatened by outsiders. However, the use of the demon lover was a wider trope in literature at this time and can be understood in this light. For example, this was also employed by Lewis in The Monk. However, Dacre reimagines the trope of the demon lover by making him a man that is actively desired by a woman.[19]

The group also discussed the role of the Devil in the novel. We debated whether Victoria could be considered evil, or whether she was merely enticed to evil by the Devil. The group was divided on this issue. Some felt that Victoria was already set on a destructive course before the involvement of the Devil. Others felt that she was manipulated by Zofloya to commit evil acts. To this extent, the novel ties into wider cultural debates in the late-Enlightenment which focused on the nature of free choice or free will.

On the whole, the group enjoyed the novel and found it an interesting and entertaining read. A few members said that they found it to be something of a page-turner. A related free exhibition ‘Black Georgians: The Shock of the Familiar’ has opened at the Black Cultural Archives in Brixton and runs until April 2016: http://bcaheritage.org.uk/programme/exhibitions/black-georgians-the-shock-of-the-familiar/

Read more about the ‘Reading Emotions’ book group.

Read more posts about the history of romantic love.

Follow Sally Holloway on Twitter: @sally_holloway

Follow Jane Mackelworth on Twitter: @jane__victoria

[1] Kim Ian Michasiw, ‘Introduction’ (1997) in Charlotte Dacre, Zofloya, or The Moor, (Oxford: Oxford University Press), (1997), (2000), 2008, p. x.

[2] Michasiw, ‘Introduction’, p. xiii.

[3] Michasiw, Introduction, pp. xiv-xv.

[4] Adriana Craciun, Fatal Women of Romanticism, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), p. 111; E.J. Clery, Women’s Gothic from Clara Reeve to Mary Shelley, (Devon: Northcote House), (2000) 2004, p. 107;.

[5] Clery, Women’s Gothic, pp. 108; 111.

[6] Diane Long Hoeveler, ‘Charlotte Dacre’s Zofloya: A Case Study in Miscegenation as Sexual and Racial Nausea.’, European Romantic Review, Volume 8, No.2, Spring 1997, pp.185-199, p.188.

[7] Clery, Women’s Gothic, p. 111.

[8] On the importance of desire in Dacre’s work see Clery, Women’s Gothic, James A. Dunn, ‘Charlotte Dacre and the Feminization of Violence.’, Nineteenth-Century Literature, Volume 53, No.3, December 1998, pp.307-327; Anne Mellor, ‘Interracial Sexual Desire in Charlotte Dacre’s Zofloya’, European Romantic Review, Vol. 13, No.2, June 2002, pp.169-173 and Pramod K. Nayar ‘The interracial Sublime: Gender and Race in Charlotte Dacre’s Zofloya. Multidisciplinary Journal of Gender Studies, 2 (3), 2013, 233-254.

[9] Clery, Women’s Gothic, p.110.

[10] Anne Mellor, ‘Interracial Sexual Desire in Charlotte Dacre’s Zofloya’, European Romantic Review, Vol. 13, No.2, June 2002, pp.169-173, p.173.

[11] Nayar, ‘The Interracial Sublime’, p.250.

[12] Nayar, ‘The Interracial Sublime’, pp.250-1.

[13] Clery, 116.

[14] Mellor, ‘Interracial Sexual Desire’, p. 169.

[15] Michasiw, ‘Introduction, Xxiv

[16] Mellor, ‘Interracial Sexual Desire,’ pp. 169-170.

[17] Long Hoeveler, ‘Charlotte Dacre’s Zofloya’ p. 189.

[18] Nayar, ‘The Interracial Sublime’, p.249-50.

[19] Adriana Craciun, ‘”I hasten to be disembodied”: Charlotte Dacre, the Demon Lover, and Representations of the Body, Volume 6, No.1, Summer 1995, pp. 75-97, p.75.