Owen Davies is Professor  of Social History at the University of Hertfordshire, and a Co-investigator on the Leverhulme Trust-funded ‘Inner Lives: Emotions, Identity, and the Supernatural, 1300–1900’ project.

of Social History at the University of Hertfordshire, and a Co-investigator on the Leverhulme Trust-funded ‘Inner Lives: Emotions, Identity, and the Supernatural, 1300–1900’ project.

Twitter @odavies9

Ceri Houlbrook is an Early  Career Researcher in Intangible Cultural Heritage at the University of Hertfordshire, primarily interested in British rituals and folklore, from the early modern period to the present.

Career Researcher in Intangible Cultural Heritage at the University of Hertfordshire, primarily interested in British rituals and folklore, from the early modern period to the present.

Twitter: @CeriHoulbrook

Project website: https://theconcealedrevealed.wordpress.com

Project Historypin site: https://www.historypin.org/en/person/66740

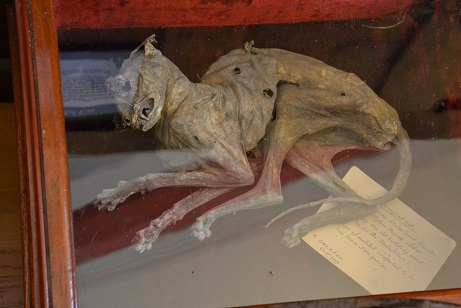

When Phil Bradley first found the bones, he thought they belonged to a child. The initial wave of horror subsided when he realised it was the skeleton of a cat, but there were still questions to be answered. Why was there a cat skeleton beneath the hearthstone of his 17th-century Cumbrian cottage? It couldn’t have become trapped in that airtight space by accident, so why would somebody put it there?

Left: Phil outside his 17th-century Cumbrian cottage; right: the hearth beneath which the cat skeleton was found

Had this cat been a one-off, we might contend that it was the sentimental interment of a household pet. But this isn’t the first cat to have been found hidden away within the fabric of a building, and nor is it likely to be the last. Cat remains have been found bricked up in walls, laid beneath floorboards, and placed in ceilings, in buildings that range in date from the 16th century to the Victorian period. And it isn’t just cats. Rats, chickens, horse skulls. Shoes, breeches, pantaloons. Poppets, bottles, and clay-pipes. A vast variety of objects, often dating to the 18th and 19th centuries, have been found in unusual locations: under floorboards, thresholds, and hearthstones; within walls; above ceilings and doors; up chimneybreasts; in the roof and thatching. Such odd places that many of them can’t have ended up there accidentally. They must have been deliberately secreted away many years ago.

58 shoes and 189 leather fragments found up the chimney and in the fireplace of a farmhouse in Nant Gwynant

But why?

It seems that very little was written about this practice at the time, so we have no text explaining exactly why these objects were being concealed; what the concealers were hoping to achieve; why those specific objects and those specific places were chosen. Without the written or oral testimony of the people who were concealing these objects, how can we hope to understand what beliefs motivated them? How can we access the emotions behind the custom?

I argue that we can’t possibly hope to know why people concealed these objects. But we can propose theories based on the body of evidence we have: the material culture of the hidden objects themselves. This is why the Concealed Revealed Project (sub-project of ‘Inner Lives: Emotions, Identity, and the Supernatural, 1300–1900’), University of Hertfordshire, has been gathering as much data as possible on these objects. Trawling through old archaeology and folklore publications, digging through Northampton Museum’s index of close to 3000 concealed shoes, and searching for obscure references online, a growing archive of hidden objects is being compiled. It’s being transferred to a freely accessible Historypin site, and members of the public are encouraged to pin their own finds of concealed objects.

Finders and scholars alike have been tossing around theories about concealed objects since the mid-20th century. The most popular proposal is that these items were hidden away to protect both home and occupants from malevolent forces, either natural or supernatural. Fire, disease, vermin; demons, witches, ghosts, and fairies. According to this theory, these items were apotropaic devices: objects used to avert evil forces.

The question remains: why would such items be considered effective supernatural safeguards? Concealed objects range from the mundane (shoes) to the distasteful (animal remains), but they certainly don’t seem inherently magical. Yet people went to the trouble of tucking them away up chimneybreasts, bricking them up in walls, or laying them beneath hearthstones. They must have invested them with some significance, some power.

Theories abound. Were shoes and other garments considered powerful because of their close association with their wearers? Were they imbued with the person’s agency? Did they act as supernatural surrogates for the people they represented, protecting the vulnerable points of a house through a process of distributed personhood? Or were they decoys, intended to lure and trap malevolent forces? And what of animal remains? Were they intended to repel vermin? If so, was it of the natural or supernatural variety?

As you’ll no doubt have noticed, we have more questions than answers. And as I said above, we can’t hope to know why people in the 18th and 19th centuries were hiding these objects: whether it was fear that motivated them or some other emotion.

It wasn’t only the original concealers of these objects, however, who engaged with them. People are frequently finding these objects in their homes during renovations, and unsurprisingly such encounters engender a range of reactions. Horror at the bones under the hearthstone. Curiosity at the shoe up the chimneybreast. Excitement at the poppet balanced on the roof beam. Anxiety over the broken bottles hanging in the attic. Even when a concealed object is discovered, its biography continues. It carries on generating emotions in people.

Three broken glass bottles found – and left – hanging in the roof space of a 16th-century inn in Kirton, Lincolnshire

And so the Concealed Revealed Project is just as concerned with the objects’ contemporary finders as with their historical concealers. How do people react when they find such odd items within the fabric of their homes? What do they do with them? Do they believe in the objects’ efficacy – even on a subconscious level? And what might this tell us about how people today engage emotionally with objects – and, through these objects, with the people who once owned, wore, used, and concealed them?

Returning to Phil and his cat, I interviewed him back in February 2016, and when I asked why he believed somebody had concealed the cat beneath the hearthstone, this is what he said: ‘the idea of burying a cat skeleton to keep the house rodent free. And there’s never been a mouse in there, in those buildings, we’ve never seen any. We’ve had rodents in here. So we thought it maybe worked. So when we re-laid the floor we just kind of put it back again. Because it seemed to be the right thing to do I think. It had been there for 200 years plus maybe, I don’t know, so it just seemed right to put this little skeleton back and we buried it. And the interesting thing is this was probably 15 years ago and we’ve still not had a mouse in there, so we’re still convinced it works.’

Further reading

Hoggard, B. 2004. The archaeology of counter-witchcraft and popular magic. In Davies, O. & de Blecourt, W. (eds.) Beyond the Witch-Trials. Manchester University Press, Manchester: 167-186.

Houlbrook, C. 2013. Ritual, Recycling, and Recontextualisation: Putting the Concealed Shoe into Context. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 23 (1), 99-112.

Howard, M. M. 1951. Dried Cats. Man 51, 149-151.

Hutton, R. (ed.) 2016. Physical Evidence for Ritual Acts, Sorcery and Witchcraft in Christian Britain: A Feeling for Magic. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke.

Merrifield, R. 1987. The Archaeology of Ritual and Magic. Batsford, London.