Last month I organized an event on ‘what to do in a spiritual emergency’ –you can see videos of the talks here. Three of my friends spoke bravely and lucidly about their own experiences – psychotherapist and film-maker Anna Beckmann, poet and transformational coach Louisa Tomlinson, and Tai-Chi teacher Anthony Fidler – and Dr Tim Read, a wonderfully wise and compassionate psychiatrist, gave us his perspective. It felt great to talk openly and sympathetically about still feels quite a taboo topic – spirituality in general is a bit of a dirty word in the very secular UK (especially in academia), and spiritual crises are even less often discussed.

I wrote about this topic in The Art of Losing Control, and it’s become particularly important to me after the mini-crisis I had last year, following my ayahuasca retreat. A friend referred to it as a ‘breakdown’ this week, which didn’t feel quite right, because it was also something beautiful and healing.

So what does ‘spiritual emergency’ mean exactly, and what can we do when they occur?

There is an overlap between spiritual / religious / ecstatic experiences, and psychosis. Psychiatry has historically viewed all religious experiences as pathological, labelling them ‘hysteria’, ‘ego-regression’ or ‘psychosis’ and ignoring any positive aspects. That’s partly because psychiatrists have tended to be anti-religious secular materialists, battling the church for authority over the care of souls.

However, some psychologists (and a few psychiatrists) have suggested an experience can be both spiritual and quasi-psychotic. This ‘transpersonal’ perspective was put forward by psychologists and thinkers like Frederic Myers, William James, Carl Jung, Aldous Huxley, Ram Dass and Stanislaf Grof – who coined the term ‘Spiritual Emergency’ and brought out an excellent anthology with that title in 1980.

However, some psychologists (and a few psychiatrists) have suggested an experience can be both spiritual and quasi-psychotic. This ‘transpersonal’ perspective was put forward by psychologists and thinkers like Frederic Myers, William James, Carl Jung, Aldous Huxley, Ram Dass and Stanislaf Grof – who coined the term ‘Spiritual Emergency’ and brought out an excellent anthology with that title in 1980.

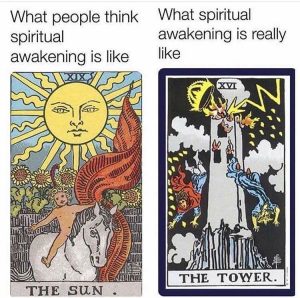

A spiritual emergency involves the sudden collapse of one’s habitual ego and customary sense of reality, and an opening to a different reality (which one could call the subconscious, or the archetypal layer, or the dream-world, or alternatively the Self or God – it’s a movement both downwards and upwards). It can involve a powerful sense of connection to all things, perhaps a transcending of time, space and matter, and a deep sense of meaning and awe. And it can also be extremely messy, painful, terrifying and dangerous, and have psychosis-like features like mania, ego-inflation, insomnia, voices, visions, ontological uncertainty and emotional disturbance. But unlike a psychotic illness, it can be a transition to growth, if handled sensitively.

Anthony told us: ‘It’s easy to get an idea of the life journey as a tidy evolution. But there’s another way humans grow, through revolution. The personality structure that’s evolved through childhood builds up like a building. And at some point in life it can be healthy for that to collapse. It can be a moment of growth, a journey forwards. But it doesn’t look like that. It looks like a piece of shit.’

Anthony told us: ‘It’s easy to get an idea of the life journey as a tidy evolution. But there’s another way humans grow, through revolution. The personality structure that’s evolved through childhood builds up like a building. And at some point in life it can be healthy for that to collapse. It can be a moment of growth, a journey forwards. But it doesn’t look like that. It looks like a piece of shit.’

Anna told us of her experience in her twenties: ‘It was the most horrifying experience I ever had, and also the most awesome.’ Louisa said: ‘A spiritual emergency is when there’s an opening between the two worlds – the spiritual and the material – but it happens without maps or guides. What could be a successful integration into a larger self and reality becomes instead intensely terrifying, a failed initiation, which instead of leading to transformation, leads to fragmentation and sometimes to annihilation.’

What are the triggers?

Both Anna and Louisa spoke of how unresolved trauma was a trigger for their spiritual emergencies. For me too, the turbulence I felt after my ayahuasca retreat was partly a resurfacing of trauma from my late teens and early 20s. Trauma seems to create an ego structure that is more prone to what Tim Read calls ‘high archetypal penetrance’ (HAP) states – the subconscious and the transpersonal or spiritual dimension gets through the cracks easier.

There may also be a genetic predisposition to altered states – you might have some genes in your family that predispose you to schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder, which make you schizotypal without necessarily developing into a psychotic disorder. One notes that in some cultures, shamanism is considered an inherited ability, as are psychic powers – a tendency to absorption or dissociation gets passed through the genes, and this can lead to creativity and insight as well as disturbance, eccentricity and illness.

More immediate triggers include being physically isolated from one’s friends and family. My crisis occurred when I was in South America, Lou’s when she was alone in Dartmoor, Anna’s when she was in New York, Anthony’s when he was in China. Tim has written about a near-crisis he had while travelling in India. Such crises can occur at moments of difficult transition – going to university, say, or breaking up from a long-term relationship.

And then there are triggers like not eating or sleeping properly, or going on a spiritual retreat, or taking drugs. Tim says he has often encountered people who’ve had spiritual crises after attending spiritual retreats – he writes about this in his excellent book Walking Shadows: Archtypes and Psyche in Crisis and Growth, and notes that retreats often shift people’s egos but fail to help them integrate their experience in the days and weeks afterwards.

What does a spiritual emergency feel like?

Both Lou, Anthony and Anna spoke of a feeling of ego dissolution accompanied by physical dissolution – they felt they went out of their bodies, and the material world seems to dissolve. I had a similar experience on ayahuasca, as many do. It is terrifying, because you don’t know if you’ll come back, so I can’t imagine what it’s like to experience that for several days or weeks. But I wonder, too, if this dissolution of the ego and material reality is an insight into the actual nature of things – Buddhists say we perceive the world as made up of separate solid things (me, the table) where actually there is a continuum of energy. Buddhist monks try to get to a state where you go beyond the perception of solid things. But it is terrifying if that happens when you’re not ready for it.

There’s also a collapse of boundaries – between the self and other people (can you read my thoughts, can I pick up your feelings and thoughts?); between you and the world (‘I can control traffic lights or even world events with my mind, it’s all connected to me’); between dream and reality. Anthony suggests we have at least two types of consciousness – a movie camera that projects waking reality, and a movie camera that projects our dreams. And in psychotic episodes, these two movies overlap, so the mythical movie of the dream-world gets superimposed on reality. Both Anna, Lou and Anthony had strong archetypal aspects to their experiences – religious imagery, messages, a sense of cosmic significance to their thoughts and acts. There can be intense surges of energy, powerful gusts of emotion, lights, visions, voices.

There’s also a collapse of boundaries – between the self and other people (can you read my thoughts, can I pick up your feelings and thoughts?); between you and the world (‘I can control traffic lights or even world events with my mind, it’s all connected to me’); between dream and reality. Anthony suggests we have at least two types of consciousness – a movie camera that projects waking reality, and a movie camera that projects our dreams. And in psychotic episodes, these two movies overlap, so the mythical movie of the dream-world gets superimposed on reality. Both Anna, Lou and Anthony had strong archetypal aspects to their experiences – religious imagery, messages, a sense of cosmic significance to their thoughts and acts. There can be intense surges of energy, powerful gusts of emotion, lights, visions, voices.

And there’s a deep ontological uncertainty. Anthony says he didn’t know if he was dead, or in some sort of altered bardo state. That was the same for me – for a week, I couldn’t work out if I was dreaming or in the afterlife. In Tim’s book, some of his case studies also don’t know if they’re dead or in heaven. It’s common on powerful psychedelic experiences to think you’re either dead or about to die. The ego interprets its dissolution as actual death. You find yourself still conscious and in some reality, but you can’t take anything for granted about how it works. In psychological terms, it’s a profound de-automatization. Your habitual automatic expectations of reality are dissolved. I would get on a plane and wonder if it would really take off or not, as if I somehow had to will it to take off (it was my dream – I was making it all happen).

What helps?

In his book, Tim Read emphasizes the importance of ‘set, setting and integration’ for navigating this sort of spiritual turbulence. This is also one of the main conclusions of my book, The Art of Losing Control.

Set refers to the mind-set one brings to the moment. In ecstatic states of consciousness – like psychedelic consciousness – our mind becomes extremely sensitive. It can swing from euphoria to terror in a moment. So you need to foster certain attitudes, above all mindfulness. Don’t worry about the past or future, focus on what is happening now. We need to try to remember ‘I’m in a spiritual crisis’ or ‘I’m tripping’ rather than get swept away by the powerful thoughts and sensations. Feel whatever you’re feeling, and observe it without attachment or aversion.

The breath is very important for this. It grounds us in the present moment, it relaxes our emotions, and it connects us to our body. Lou speaks of the ‘silvery chord of my breath’ being the only thing that connected her to her body and to physical reality. Someone once said we’re spiritual beings having an in-the-body experience – we need to connect to the body, enjoy this sensual material reality (nature is good for this too, so are hugs). It was also hugely important for me, in moments of panic, to breathe slowly, and remind myself ‘this will pass’.

A second important attitude is humility – not giving way to ego-inflation and Messianic grandiosity. Anthony says: ‘If you think you’re Jesus or the Buddha, that’s OK. But you’re also this person. And if I’m the Buddha, so are you.’ You have a glimpse of the infinite Self within you. But it’s within everyone, not just you. Relax. Don’t take yourself or the experience too seriously. You’re not controlling the universe. Have a sense of playfulness. Anthony talks about having an open and curious attitude to one’s experience – what does it feel like? How does this reality behave?

Third, we need to take care of ourselves. Yes, you’re the infinite cosmos, but you’re also this particular being in this particular body. Have patience and compassion for your ego and body. Look out for yourself – make sure you eat and sleep, don’t put your body in danger. Be polite, pay for things, even if you think it’s all a dream. Self-compassion is the key – even when I felt very alone and frightened, I rooted for myself. I was on my side, no matter how much the volatility swept away my tidy life-plans.

Secondly, setting is crucial. It helps if you have loving, understanding friends to support you while you are ‘transitioning’. When I came back from South America, I couldn’t tell what was real, I could barely understand conversations, and luckily my friends were there for me, and weren’t freaked out, because they’d had similar experiences (Lou is one of my best friends). I loved getting hugs from my friends, I loved stroking my brother’s dog and cat, I loved sitting by his fire – I grounded myself in love and touch. Getting out into nature was also really healing for me. I avoided seeing people who wouldn’t get what I was going through.

Third, integration is very important. I came back to this reality within a week or so, but worked on the integration for several months, and am still working on it. I started seeing a therapist who is open to the transpersonal perspective. I found a community where I could practice meditation with others. There are also communities like the Spiritual Crisis Network and the Hearing Voices Network which offer support.

Sadly, western psychiatry is often the worst setting or integration process for this sort of experience. As Tim told us, most psychiatry is meaningless – it doesn’t accept that these sorts of experiences could have meaning, could be a stage in a person’s growth. Tim writes: ‘the medical intervention often serves to entrench stasis and impede growth’. Anna really wanted support during her crisis, but was terrified of being locked up and treated as totally mad. She was lucky, probably, not to be sectioned – most secure psychiatric wards are horrible, harsh, loveless and soulless places. Tim, who led the Emergency Psychiatry Service at Royal London Hospital, writes: ‘It is one of the great tragedies of psychiatry that our most vulnerable people are placed in the most unsuitable settings.’

And western culture is also rather an inhospitable and even hostile setting for such experiences – we don’t talk about them, and we see messy breakdowns as awful, shameful and frightening, something to hide away, rather than potentially something painful but wonderful, like giving birth!

However, just as there is a risk of materialist fundamentalism, there is also a risk of religious or spiritual fundamentalism – Anna talks about how she would feel these ecstatic experiences and hunger for them, but she came to see this was a way of bypassing her pain. We can use our spiritual experiences as ways of not dealing with this reality, this body, this life with all its messiness. Tim Read writes about one case study of spiritual narcissism, a young man who focused so exclusively on his spiritual experiences that he lost the capacity to negotiate this world. We need to balance our life in this world with our yearning for the transcendent, so we don’t become a ‘total space-cadet’ as one ayahuasca facilitator put it to me. We also need to be open to ambiguity and uncertainty, to sometimes not knowing precisely where we are on the path.

None of this is meant to deny that there are psychiatric illnesses which are mainly physical in origin, and which are not transitions to higher selves. I also know that, for some people, psychiatric medication is helpful and even life-saving. And sometimes being sectioned is necessary to protect people and society.

Tim and I are now going to put together a book of people’s first-person accounts of spiritual experiences, to answer the questions – what are they like from the inside, and what did people find helpful? The focus is on the practical things that help people, the set and setting. If you’d like to contribute, more details can be found here.

Finally, I wonder what these experiences say about the nature of reality and God. I think evangelical Christians can have a naïve view of God and the tidiness of religious experiences. You meet Jesus, who is totally loving and good for you, and instantly both this life and the afterlife are better. In fact, spiritual awakenings often feel like death, and can totally mess up your life. They’re closer to the God of the Old Testament, the God of the Burning Bush and the Book of Job, the God who turned Nebuchadnezzar into a beast and made Ezekiel lie on his side for 430 days.

What does it say about God, or the Self, that sometimes spiritual awakenings can destroy a life, can actually lead people to starve themselves or jump off a building in their search for transcendence (two instances mentioned in Tim’s book).

To me it suggests that sometimes the dissolution of the ego and the opening to the Self is incredibly rough, sometimes fatal. It can be a confrontation with a Shiva-like god – the cosmic creator and destroyer. It makes me hope that reincarnation is real, so we can hope that, while the archetypal call of the Self is sometimes harmful and even fatal to the individual, eventually, over many lives, we move towards the light. Or maybe God / the Self / the Tao doesn’t care about individuals, only the awakening of the species. Or maybe there is no God. Even if there isn’t, we can still help people navigate these rough moments of ego-dissolution, so that they can move towards positive and fulfilling lives, as Lou, Anthony, Anna and I have done.

Tim and I are now co-editing a book of first-person accounts of spiritual emergencies, with a focus on what practical advice can we share for people going through them. Find out more, and submit your synopsis for a chapter, here