Amy Dolley took the History of Emotions undergraduate module at Queen Mary University of London during 2017-18. In this post, one in a series of contributions by QMUL students to the History of Emotions blog, Amy introduces and explains the unfamiliar emotional state of ‘dépaysement’.

Amy Dolley took the History of Emotions undergraduate module at Queen Mary University of London during 2017-18. In this post, one in a series of contributions by QMUL students to the History of Emotions blog, Amy introduces and explains the unfamiliar emotional state of ‘dépaysement’.

Ever since I can remember I have been absolutely terrified of snakes. It’s not the most bizarre phobia – in fact, lovers of snakes are usually the ones to face more judgement – but it is definitely a severe one in my case. The exact reason why I detest the reptiles so strongly I cannot discern for sure. Perhaps it has something to do with an early experience of Sunday school Genesis teachings, which ingrained in my mind the association of snakes with Satan himself, or merely the understanding of the fatality just one bite can cause. Whatever the reasons, I have grown up extremely fortunate to live on an island where the beasts do not roam in the wild. That is, until recently.

After months of saving, myself and a friend travelled to Indonesia last summer. The moment I set foot on the warm and alien Indonesian ground, I felt an emotion that I was unable to articulate – one of excitement, nervousness, curiosity and insecurity. A few days into our travels, we found ourselves in a beautiful little village at the top of a mountain. It was here where a friendly local approached me with a mammoth snake draped around his shoulders and asked me if I wanted to hold it. If this had happened back at home, even in the comfort of a zoo, I would have certainly refused but, fuelled by this strange emotion I have just attempted to describe, I said yes. I was still terrified, but the new environment I found myself in seemed to enable me to step outside of my comfort zone and overcome my phobia.

So how do we describe this rush which pushed me towards a brief cuddle with one of my biggest enemies? The French have a word which encapsulates this emotion and is unique to their language: dépaysement. According to the Collins French-English Dictionary, this is a noun that refers to the feeling of disorientation that occurs when you find yourself in a country that is not your home. If we deconstruct the word, we can discover a little more depth to this definition. The French word pays translates as country, and dépayser means something like ‘to disorientate’. Many have speculated that dépaysement literally means ‘decountrification’.

In The Book of Human Emotions, Tiffany Watt Smith argues that this word is typically French, as “the French seem to be particularly intrigued by emotions to do with disorientation.” She then gives the examples of ilinx (the strange exhilaration that comes with causing chaos) and l’appel du vide (the frightening urge to leap to one’s own death) to affirm this claim. However, one doesn’t have to be French to experience dépaysement. Emotions that we recognise and that are similar to it include homesickness, nostalgia, and wanderlust, and we will look at examples of people from different countries experiencing dépaysement in a while.

One also doesn’t need to be aware of the term dépaysement and its meaning to experience it either. A lovely example of this is described by mother Mona Rasmussen who, in the Globe and Mail, describes her adopted eleven month old daughter experiencing dépaysement. Her baby, Grace, was born in China but moved to Canada with her new mother when she was a few months old. Rasmussen recalls Grace’s look of longing when a man next to her spoke in her mother tongue, and describes her as turning towards him “…the way a flower turns toward the sun.” Rasmussen believes her daughter was feeling dépaysement that day – a longing for her home country.

Although its definition does not label it as a positive or negative emotion, dépaysement has historically been regarded as the latter – the reasons for which we will explore in a moment. My purpose is to show how dépaysement can be a wonderful thing which enables us to overcome fears and discover a new side of ourselves, if it is embraced correctly.

Dépaysement has a strong presence in French literature, and – as aforementioned – has tended to be depicted as a negative emotion. Joseph Gerard Brennan’s study of three novels of dépaysement provides examples of popular works which have described it as sparking immoral behaviour: L’Immoralise, The Ambassadors and Der Zauberberg. André Gide’s L’Immoraliste, for example, tells the story of Michel, who travels to Algeria with his wife on their honeymoon. In this foreign land Michel discovers a “new self” and is described as descending into immorality, particularly because of his sexual encounters with young Arab boys.

Gerard explores the prominent theme of dépaysement in the three novels mentioned – all published in the early twentieth century – and this negative narrative of the French emotion also exists in other novels, such as Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1902) and William Golding’s Lord of the Flies (1954). Similarly, these two stories describe the protagonists’ decent to savagery which occurs when they enter exotic lands.

Gerard explores the prominent theme of dépaysement in the three novels mentioned – all published in the early twentieth century – and this negative narrative of the French emotion also exists in other novels, such as Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1902) and William Golding’s Lord of the Flies (1954). Similarly, these two stories describe the protagonists’ decent to savagery which occurs when they enter exotic lands.

Whilst I disagree that dépaysement leads to an erosion of morality, its portrayal in literature does show how it has long been regarded as a negative emotion. However, the real danger in dépaysement that needs highlighting is the association of it with national identity. The renowned early twentieth-century anthropologist, Bronisław Kasper Malinowski, provides evidence of this in his various studies of indigenous cultures, most notably in Argonauts of the Western Pacific.

In his book of anthropological essays, Transcendent Individual, Nigel Rapport demonstrates how Malinowski shows how European travellers have been overwhelmed by their encounter with dépaysement, and have resorted to racism to explain the feelings it brings. Malinowski describes this as a “continuous ethical conflict” and he should be celebrated for highlighting and attempting to dissolve this.

This conflict was heightened by the remarkable improvements in travel that occurred a few decades prior to Malinowski’s career. Ships were beginning to sail around the globe, such as The Great Eastern, which could take 4,000 passengers from England to Australia and reached nearly every corner of the British Empire. A boom in railways and the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 also enabled more people to visit African and Asian colonies. More and more Europeans were experiencing dépaysement as they found themselves on unfamiliar soil, and the prevailing colonial attitudes at the time certainly resulted in an association with the feeling of unfamiliarity with an assumption that home really was the best place to be.

In her article, ‘Cats and Poets in Old France’, scholar Eve Drobot gives an insight into dépaysement’s reputation in France, claiming that “it has long been a negative notion to the French, a people whose sense of self derives traditionally from a sense of place.” Although this is a massive generalisation, Drobot is alluding to dépaysement’s potential to encourage imperialism. It is possible for one to visit a country foreign to them and, after sensing the dépaysement, blame the feeling of uncertainty on the country itself, and not homesickness. It also works the other way round – a strong sense of pride over home can hinder one from embracing dépaysement in a way that allows a positive and exciting adventure.

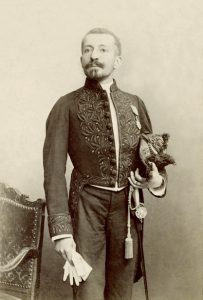

However, the history of dépaysement is not entirely dark and in the same article Drobot does admit that, in recent years, it has endured a new, optimistic approach, particularly in academic spheres. One individual who has shed a positive light on dépaysement is the French author Pierre Loti. He was a French naval officer who, in the late nineteenth century, documented his travels to various countries, including Tahiti, Japan and Senegal, and the word dépaysement crops up a lot in his work. He writes that his first experience of the emotion occurred when visiting family in France and, instead of discovering that dépaysement led to immorality or nationalism, Loti enjoyed the sensation. It is interesting that he does not deny that a degree of sadness does come with dépaysement, as he misses home, but he delights in this and writes about the joy and excitement it brings too. For Loti, the charm of dépaysement is found within the blend of feelings that it produces and his various works, such as Aziyadé, Le Désenchantées and Le Roman d’un spahi are a testament to this.

We can learn a lot from Loti, who strongly resented European imperialism. He shows how we should regard dépaysement as a form of wanderlust, not homesickness, and I encourage you to fully embrace the emotion when you next travel away from home. When asked on twitter what dépaysement means to her, Marie Thouaille writes that she regards it positively and enjoys the refreshing quality of being in a new environment.

https://twitter.com/legomarie/status/976490812493180929

If we approached visiting new places with this attitude, it would certainly aid the breakdown of divisions between cultures and nationalism whilst allowing the individual to experience something new – and potentially defeat a phobia! In his short 1982 New York Times article, ‘Discovering the Hidden Paris’, John Vinocur instructs travellers on how to deal with their feelings of dépaysement in Paris in particular, asking visitors to “…[embrace] its alienness, its exoticism and its vitality by running after what is both common and hidden.” There is certainly a vogue for foreign emotional words today, and I hope that dépaysement does not remain a fleeting fashion, rather it becomes a way of life which enables us to experience new places and, as a result, discover new aspects of our character.

Follow Amy on Twitter: @AmyDolley

Further Reading

Jean Anderson, “Dépaysements/Becomings: The Role of the Randell Cottage Writers Residence”, New Zealand Journal of French Studies, 35:2 (2014)

Lesley Blanch, Pierre Loti: Travels with the Legendary Romantic (Tauris, 2004)

Eve Drobot, “Cats and Poets in Old France: The Great Cat Massacre and other Episodes in French Cultural History”, The Globe and Mail (1984)

Joseph Gerard Brennan, “Three Novels of Dépaysement”, Comparative Literature, 22:3 (1970)

Jean-Michel Rabate, Writing the Image after Roland Barthes (University of Pennsylvania Pres, 2012)

Nigel Rapport, Transcendent Individual: Essays Toward a Literary and Liberal Anthropology (Routledge, 2002)

Mona Rasmussen, “A Piece of the Past”, The Globe and Mail, 2014

Stanley Walker Rockwood, A Comparative Study of the Works of Pierre Loti and Joseph Conrad (University of Wisconsin, 1929)

John Vinocur, “Discovering the Hidden Paris”, The New York Times (1982)

Clive Wake, The Novels of Pierre Loti (Mouton, 1974)

Tiffany Watt Smith, The Book of Human Emotions: An Encyclopedia of Feeling from Anger to Wanderlust (Profile Books, 2015)