Agnes Arnold-Forster and David Saunders reflect on their experiences of public engagement in Gateshead.

This year, the theme of BBC Radio 3’s Free Thinking Festival was ’emotion’ and one of the Wellcome Trust-funded projects housed in the Centre for the History of Emotions, ‘Living with Feeling’, was invited to take part. Founding Director of the Centre and ‘Living with Feeling’ project PI, Thomas Dixon, project manager Agnes Arnold-Forster, radio producer Natalie Steed, and project PhD students Edgar Gerrard Hughes, David Saunders, and Evelien Lemmens, travelled up to Newcastle on Friday 29th March and spent the weekend engaging the public with the history of emotions.

Thomas kicked off the weekend with his lecture on the emotional weather of Britain, past and present. In ‘Feelings, and Feelings, and Feelings’, he moved from C S Lewis to Seneca; from Paul Gascoigne to Princess Diana; and from Charles Dickens to emotional outbursts on social media. He aimed to bring a cool head and some much-needed historical perspective to the often over-heated emotional atmosphere of twenty-first century politics and social media, and to show how our emotions themselves have a history. The lecture is one of the resources available in the ‘Audio’ section of our new Emotions Lab website, which we also launched at the festival.

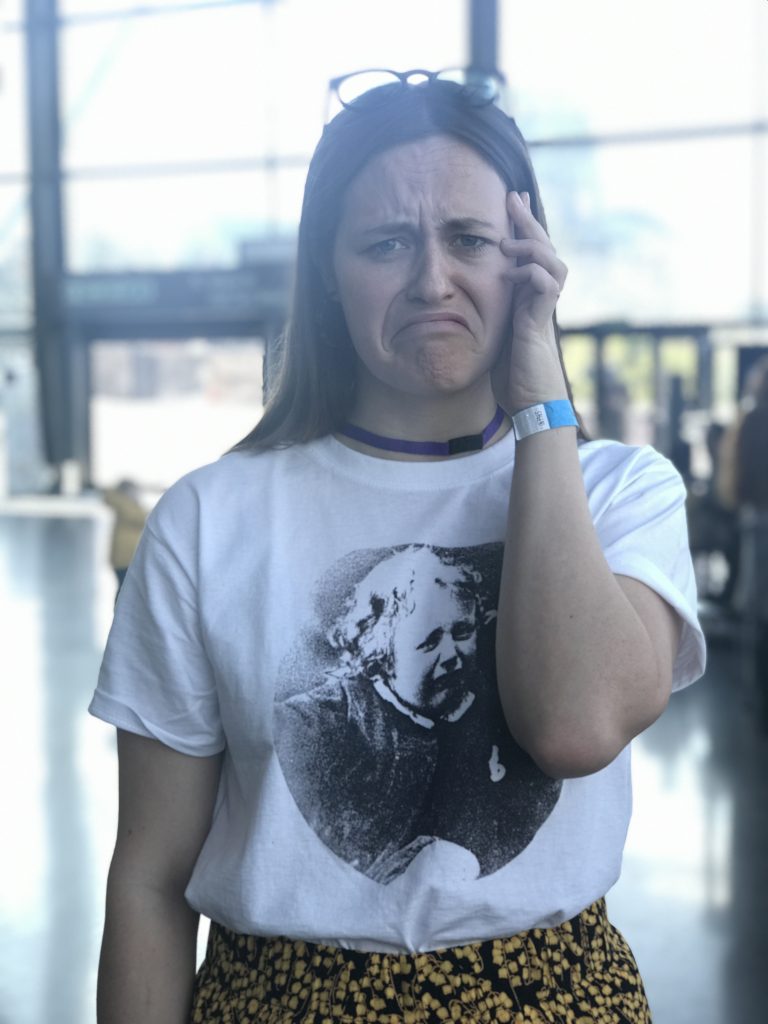

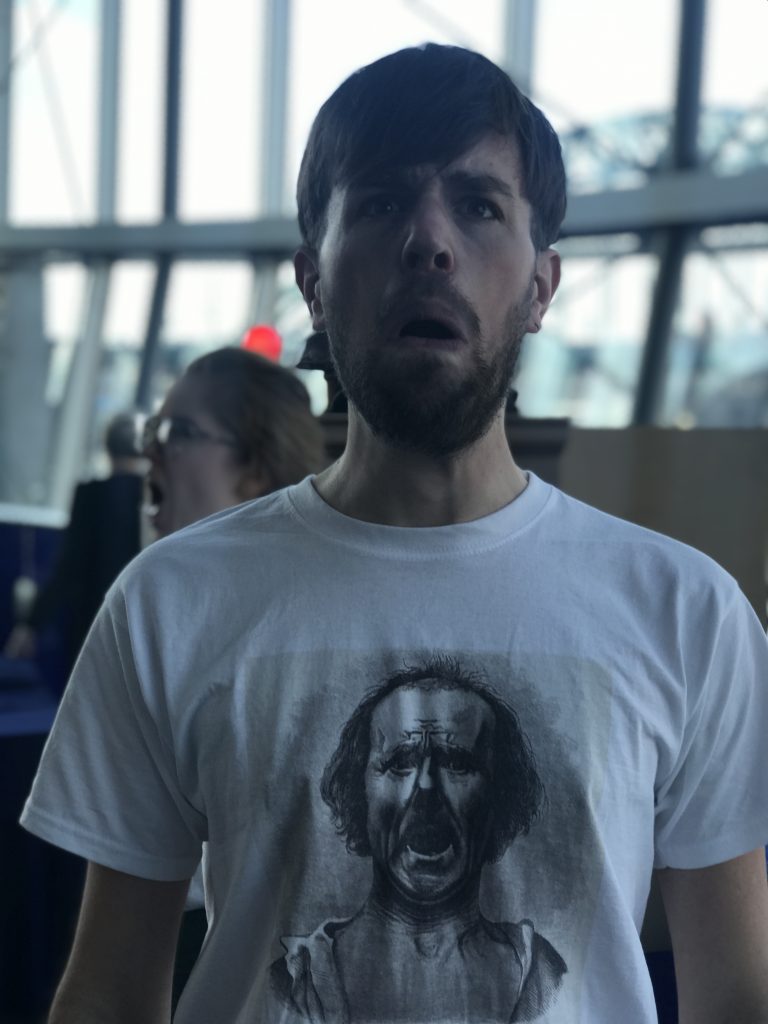

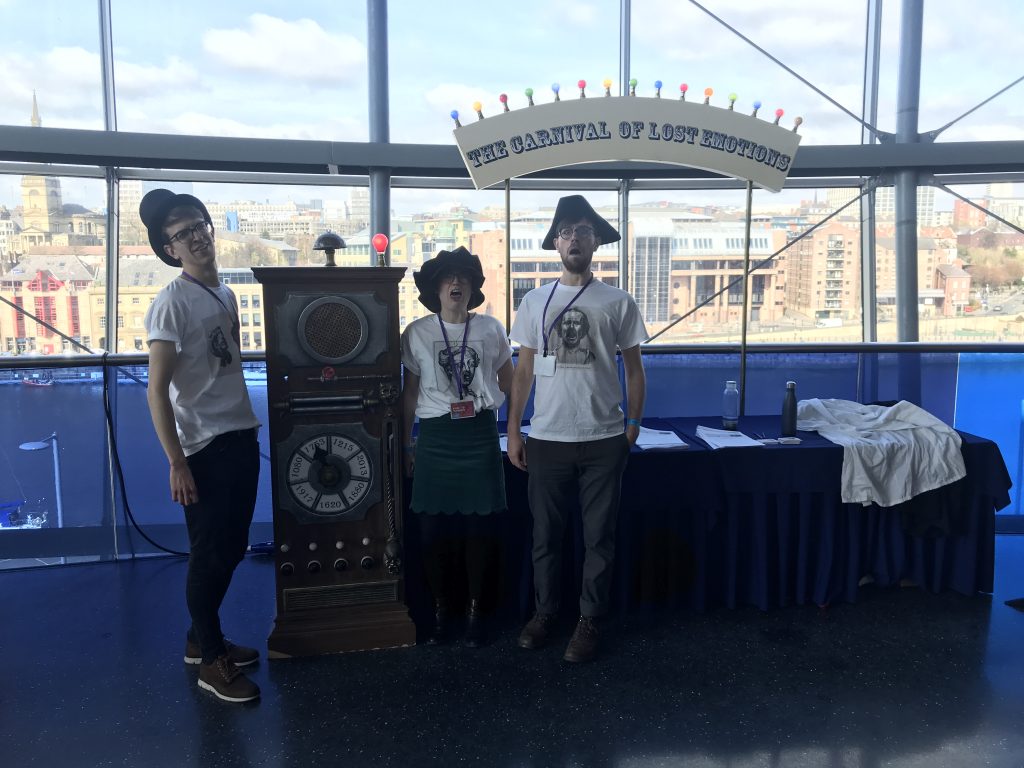

Living with Feeling Project Team and the Lost Emotions Machine. The Project had t-shirts made, each with drawings or prints of different emotional expressions from history.

Afterwards, Agnes roamed the Sage’s concourse with Natalie to speak to attendees and ask their opinion on some of Thomas’ ideas and provocations. For many, the lecture was their first exposure to the history of emotions and offered them a new perspective on their feelings and the presence of emotions in public life. One audience member who trains therapists in the North East said that listening to the lecture has prompted him to re-think some of his professional practice. He referenced Thomas’ comments on the ‘stiff upper lip’ of his parents’ generation to the ‘much more emotional approach that millennials bring to things’ and reflected on his own work with clients of different ages. He said that Thomas’ lecture made him more ‘conscious of how subtly different the emotional mind-sets of older and younger people might be’ and told us that he’d factor these differences into his work.

Thomas also managed to convince people of the value and twenty-first-century applicability of Roman philosophy. One audience member wrote, ‘I never thought I would read Seneca or align myself with Stoicism! But I have downloaded and started to enjoy De Ira!’

Thomas’ labours for the BBC were many. He also discussed the language of emotion with filmmaker Harriet Shawcross, US diplomat William J Burns, and musician Kathryn Tickell on Start the Week; was filmed for BBC Ideas; was featured on In Tune; and gamely stood in for chicken-pox-ridden Tiffany Watt Smith to discuss ‘twenty words for joy’.

On the Sage’s concourse, other members of the project were on hand to take people back in time with the Lost Emotions Machine. Visitors took turns to choose a year – 1753, for example. Using magic (with some help from an HP printer), the machine produced an emotion from that historical period that we either no longer experience or has had its meaning much changed. These ‘lost emotions’ were used as a starting point for conversations about the connections between emotion and the political, social, cultural, and economic context of any given period of time and to prompt debate about the changing nature of human feeling and human expression.

The Lost Emotions Machine gained us many fans, and Sarah Chaney was interviewed by BBC Radio 3 about it for an article on the Free Thinking website. When asked whether they had ever considered the history of emotions before, one visitor wrote, ‘No, and to be honest the idea of a Centre for the History of Emotions struck me as bizarre. But I was quickly won over and have signed-up to the email list!’

Another visitor we interacted with initially expressed scepticism about the very notion of the history of emotions, asking if the term was ‘an oxymoron’ since ‘emotions don’t have a history’ and have ‘always been the same’. The Lost Emotions Machine took him back to 1753 and produced ‘Nostalgia’. After explaining to the visitor and his son the history of the term – as a distinct and purportedly fatal psychiatric condition during the eighteenth century before its transformation into the more benign and even pleasurable psychological phenomenon it is perceived as today – we asked him how this made him think about emotions in history. The visitor said that he was now ‘completely convinced’ by the idea of emotions having a history, given how different the nostalgia of the eighteenth century was to his present-day understanding, and said that he ‘retracted’ his earlier view.

Many of the people we engaged with over the weekend were health professionals or told us their own experiences of emotional or mental ill-health. One visitor to the Lost Emotions Machine reflected on his time-travel and wrote that it was,

…always helpful to be reminded of the socially constructed nature of our reality – especially when my discipline (psychology) tends to veer towards a fairly reductive essentialism.

For another visitor we spoke to, the Lost Emotions Machine provided the foundation for a conversation about how the history of emotions might be used to understand and reinterpret one’s own experiences of disability, depression, and pain. The Machine produced ‘Melancholia’, and we discussed the complicated relationship between the condition and modern ideas of depression, with all of us agreeing that depression was a condition intrinsically linked to modern political, social, and economic conditions rather than constituting a universal, unchanging human experience. The visitor, who was a wheelchair user and who self-identified as having bipolar disorder, said that while she had not come across the history of emotions as a field before, it supported and confirmed her own experiences of how feelings could be embedded in a particular historical and linguistic context.

The visitor mentioned receiving therapy for both physical pain and her bipolar disorder, both of which encouraged her to alter her relationship to physical and emotional stimuli – for example, to reinterpret pain as passing discomfort rather than a permanent source of unhappiness. Historical studies of emotions, she noted, seemed to make possible a similar kind of renegotiation and perhaps even liberation from apparently ‘inescapable’ feelings.

The weekend was interesting, entertaining, and emotional, not only for the visitors but for us as well. Our time in Gateshead further demonstrated history’s capacity to change people’s perceptions of their own emotional weather, improve their emotional literacy, and ameliorate their emotional health.