May El Mantawy took the History of Emotions undergraduate module at Queen Mary University of London during 2020-21. In this post, one in a series of contributions by QMUL students to the History of Emotions blog, May explores the dark history of hysteria.

We are living in hysterical times – especially now, with ‘pandemic hysteria.’ Whenever someone overreacts or there’s a lot of noise surrounding a situation, it’s classed as ‘hysteria’ or ‘hysterical.’ But the conflation of uproar and mass fear as ‘hysteria’ has made us lose sight of its history. Today, we’d determine that hysteria means excitement or emotion that is uncontrollable, yet the foundation of the term is rooted in oppression and misogyny.

‘Hysteria’ comes from the Greek word ‘hysterikos,’ meaning ‘suffering of the womb.’ Greek thinkers like Hippocrates and Plato believed that when a woman experienced delirium, excessive emotion, and lack of self-control, this was because her uterus was moving freely throughout her body and having tumultuous effects on her mental wellbeing. Plato believed that when the womb was empty for too long after puberty, it became distressed and disturbed and started to move around the body out of irritation. Just the root of the word shows that the term has been characterised as a woman’s emotional condition and illness from its inception; an illness that required treatment.

‘Treatment for a Wandering Womb’ from The Wandering Womb: A Cultural History of Outrageous Beliefs About Women by Lana Thompson (1999)

This gave the impression that women should be quick to occupy the womb – they were told that they needed to be getting married and carrying babies to anchor the womb. The threat of sexual deprivation and barrenness sending women crazy spurred the myth of the wandering womb, solidifying women’s position as strictly child-bearers. It also solidified excessive emotion as a feminine emotional condition, and boxed women in as an emotional gender. This mentality persisted, with Roman medical authors still considering hysteria to be an issue with the female generative system caused by ‘diseases of the womb.’ and it remained that when a woman experienced mental disturbance, stress, panic or uncontrollable behaviour, it was seen as another case of hysteria.

Fortunately, physicians looked elsewhere for the cause of hysteria. In the 17th century, Charles Lepois was one of the first to assert that “the seat of hysterical pathology was neither the womb nor the soul but the head.” This type of thinking started to shake the foundations of the prehistoric relationship between a woman’s reproductive system and her physical wellness. Although the focus of hysteria had shifted, it was still considered to affect women more than men, with Thomas Sydenham acknowledging that whilst some men could experience symptoms of hysteria, “women were constitutionally predisposed to hysteria due to their fragile nervous apparatus.”

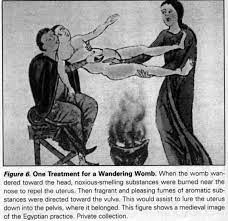

Jean-Martin Charcot’s study on hysterical patients from ‘What is Hysteria?’ by the Wellcome Collection

Even as the physicians shifted from womb, to brain, to the mind, women were still considered the most hysterical patients. Jean-Martin Charcot explicitly claimed that men and women alike experienced hysteria, but he’s largely been linked to controversial treatment methods, including electronic massages via the vagina, and examining female patients to study hysteria – still resting on the belief that hysteria developed through the female reproductive system and characterising hysteria as a woman’s emotional state (as seen below).

Although studies shifted towards more plausible explanations for hysteria, like neurology and mental wellness, it wasn’t really until men returned from WWI with symptoms of hysteria that, today, we’d consider to be PTSD, that emotional pain was seen as something that needed to be taken seriously. Physicians continued linking hysteria with femininity, and this is an issue that’s still relevant in contemporary history and current events. We as a society have a problem with classifying women who express any emotion as hysterical, but celebrate men who do the same. We see this frequently in reports of female fans of male artists – almost always, they are called hysterical.

The use of ‘hysteria’ or ‘mass hysteria’ to describe female fans increased when The Beatles burst onto the music scene in the 1960s and pandemonium surrounding them was termed ‘Beatlemania.’ Attendees at The Beatles’ live shows described scenes that were “almost like collective hypnotism” and recalled how female fans were fainting, screaming and wetting their seats – actions linked to symptoms of hysteria, shown in the image below. Critics of The Beatles fans doubted the mental stability of young female fans; Paul Newman even called them the least fortunate of their generation and idle failures.

The way that male critics typified female fans of The Beatles as degenerates and hysterical shows how negatively women are viewed when they express emotion or excitement. The negative outlook on female fans is closely tied to misogyny and dated gender expectations. Barbara Ehrenreich’s 1992 essay suggests that hysteria and obsession with adult men is a form of protesting sexual repressiveness, breaking free of rigid standards placed on young women in a way that wasn’t considered proper or politically correct.

It’s intriguing how the image of mass hysteria is tied to female mass hysteria – an image of sobbing, screaming and fainting women, overcome with uncontrollable erotic energy. When we shift focus to mass male hysteria, it’s described as drunken destructiveness – a rampage of uncontrollable masculine passion. Take football fans as an example: they shout and become aggressive and emotional in a way that they can’t control. This indicates that men suffer from hysteria and uncontrollable emotion, except they aren’t described as ‘hysterical’ like women are. They’re called ‘passionate’ and ‘opinionated’ football fans, but their lack of control over their emotions is the same as female fans.

Lisa Lewis’ investigation into fan behaviour shows that male football fans are usually socio-economically disempowered men who find empowerment in their actions at football matches and so their hysteria is assertive. When female fans exhibit similar actions, they’re seen as overstepping boundaries of proper feminine behaviour and of low intellect. See the below comparison of female music fans and male football fans.

Fans of Justin Bieber from ‘Justin Bieber Arrested, Mug Shot Revealed, All of the Tears’ by John Walker

This is because, as Elke Krasny puts it, the history of hysteria is the history of patriarchy, and to indicate that men experience the emotional condition of hysteria is to indicate that they are unstable and unreliable. Hysteria is emotion in excess – men can harness their emotions for their benefit, but women don’t have the mental capacity to deal with it. Hysteria is rooted in misogyny and controlling sexual behaviour of women, and this still dominates the treatment of women, their emotions, and their health today. Even when it comes to politics, authoritative and passionate female politicians are seen as unhinged, yet their male counterparts are seen as passionate and bold. Trump can be angry; Harris must remain collected (below). Diagnosing a woman as hysterical impairs her ability to effectively engage with her target audience – the gendered historicization of hysteria has served to silence and repress strong women and continues to do so today, and we need to change that.

Further Reading:

Antony JW. Taylor, ‘Beatlemania’ and Mass Hysteria – Still a Much Neglected Research Phenomenon, Journal of Psychology and Psychotherapy

Lisa A. Lewis, The Adoring Audience: Fan Culture and Popular Media (Routledge: London, 1992)

Mark S. Micale, Approaching Hysteria: Disease and Its Interpretations, Princeton University Press

Elke Krasny, ‘HYSTERIA ACTIVISM: Feminist Collectives for the Twenty-First Century,’ Performing Hysteria: Images and Imaginations of Hysteria

Dorian Lynskey, Beatlemania: ‘the screamers’ and other tales of fandom, The Guardian

Rob Boddice, The Arch of Hysteria, REMEDIA

Jude Ellison Sady Doyle, “Hysterical” Women Have Been Making Men Nervous Since The 1900s. Kamala Harris Does The Tradition Proud, Elle

Sarah Jaffray, What is Hysteria?, Wellcome Collection

B.B. Wagner, Beware the Wandering Wombs of Hysterical Women, Ancient Origins

Ada McVean, The History of Hysteria, McGill