The physicist Lawrence Krauss recently argued that education should teach all children the central tenet of science – ‘nothing is sacred’. Not God, not human rights, not democracy, not the environment. Nothing.

Emile Durkheim, one of the founding fathers of sociology, would disagree. Durkheim argued in The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912) that, though no one should dispute ‘the authority of science’, we still need religion to bind us together and to renew our moral and social consciousness through what he called ‘collective effervescence’.

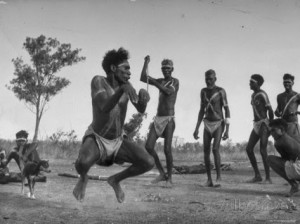

He used Aboriginal society as an example of religion in its purest and earliest form. Aboriginals would periodically gather together for festivals, and a sort of electricity arose between them, a ‘power’, ‘a charge’, a ‘potentiality’. They would eat together, dance together, cry, chant, self-intoxicate, perhaps even swap wives, and get into such a state of delirium that they were transported beyond their individual selves, and filled with the spirit of the tribe. The totemic symbols of their tribe reminded them, in calmer times, of this exalted state of collective consciousness.

He used Aboriginal society as an example of religion in its purest and earliest form. Aboriginals would periodically gather together for festivals, and a sort of electricity arose between them, a ‘power’, ‘a charge’, a ‘potentiality’. They would eat together, dance together, cry, chant, self-intoxicate, perhaps even swap wives, and get into such a state of delirium that they were transported beyond their individual selves, and filled with the spirit of the tribe. The totemic symbols of their tribe reminded them, in calmer times, of this exalted state of collective consciousness.

We might call this exalted state of consciousness ‘ecstasy’, but that has supernatural connotations. Durkheim is at pains to show that this ‘collective effervescence’ (or group fizz, if you prefer) is actually perfectly rational, natural, and necessary to tribal functioning. Man is connected through such rituals not to God but actually to the tribe. Religions celebrate and perpetuate society – ‘the idea of society is the soul of religion’.

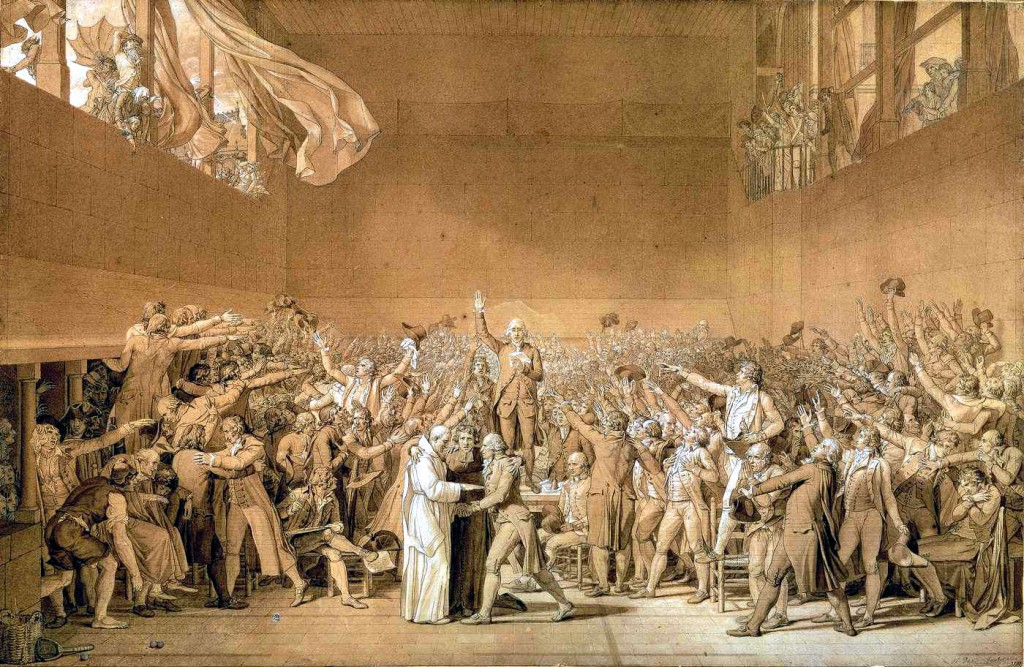

We may have lost touch with Jehovah, but we still need these periodic orgies of collective effervescence to rejuvenate our collective moral and tribal consciousness. Durkheim was a lapsed Jew and a devout citizen of France, and thought the French Revolution was a great example of secular effervescence. He wrote:

Society’s capacity to set itself up as a god, or to create gods, was nowhere more visible than in the first years of the Revolution. In the general enthusiasm of that period, things that were purely secular were transformed by public opinion into sacred things: homeland, liberty, and reason.

The Elementary Forms was published a few years after William James’ Varieties of Religious Experience, and the two books attempt a scientific analysis of religious ecstasy from opposite poles. For James, religious experience is the individual soul in commune with the divine – he has no interest in collective ecstasy. For Durkheim, religious experience is always social and tribal – he has no interest in individual ecstasy. The truth must be somewhere in between.

But both share the idea that in ecstatic moments, we somehow transcend material determinism and access what Durkheim calls the Ideal, from which we draw power and inspiration down into material reality. So ecstasy is a bridge between two worlds – the material-empirical, and the ideal or spiritual.

James is prepared to suggest that this ‘other world’ of the spiritual genuinely exists. Durkheim is more wary – he puts forward a sort of emergence theory of collective consciousness.

Every other species, he says, is biologically-determined, lacking in free will, and confined to the material realm. Only humans have the capacity to transcend the material realm and to access the Ideal. We have this capacity through the chemical fusion of ‘collective effervescence – all our individual consciousnesses come together and create such an electrical charge, such a fizz of effervescent bubbles, that we can leap into the Ideal, and bring back ideas and symbols which become actualized in the material world. This is all entirely natural and human – gods are just ideas, as real as any other idea, as long as we believe in them.

This is an interesting theory, and could be compatible with Giulio Tononi’s Integrated Information Theory of consciousness. But humans aren’t the only animals to gather together – why don’t bees or wildebeest also achieve transcendent consciousness when gathered together? Why do most great religious visions or scientific discoveries happen to individuals when they’re on their own? And why does collective effervescence sometimes lead not to moral advance but moral regression?

Durkheim thought Europe in 1912 was in a state of ‘moral mediocrity’ – ‘the ancient gods grow old or die, and others are not yet born’, he wrote, sounding like JRR Tolkien. But ‘a day will come when our societies will once again experience times of creative effervescence and new ideas will surge up’, new festivals, new symbols, new gods.

Well, be careful what you wish for. He noted in passing that effervescence can lead to barbarism, bloodshed and attacks on ‘scapegoats’, as in the Crusades, and this is just what happened a few decades later with the Nazis, an ecstatic new cult of the state, led by a man who was the embodiment of Durkheim’s description of the demagogue: ‘He is no longer a simple individual speaking, he is a group incarnate and personified’.

Since then, western thinkers have been understandably wary of looking for ways to ferment ‘collective effervescence’ for political means. But there has been a return to Durkheim’s ideas in the last few years, notably in philosophers like Martha Nussbaum and Simon Critchley, and the psychologist Jonathan Haidt, whose TED talk on ‘ecstasy and the hive-mind’ is a contemporary riff on Durkheim.

Since then, western thinkers have been understandably wary of looking for ways to ferment ‘collective effervescence’ for political means. But there has been a return to Durkheim’s ideas in the last few years, notably in philosophers like Martha Nussbaum and Simon Critchley, and the psychologist Jonathan Haidt, whose TED talk on ‘ecstasy and the hive-mind’ is a contemporary riff on Durkheim.

Durkheim’s ideas are a useful way of understanding some contemporary political problems. You can see the Charlie Hebdo attack as a clash of sacred narratives, for example. Muslim radicals see the cartoons of the Prophet as taboo, and therefore punishable, and they think the democratic state is a false god. For French Republicans, the Republic is sacred, and any attack on free speech is taboo.

Durkheim’s work also helps us understand the United States’ continued inability to control gun sales. The Constitution is sacred, the United States is sacred, its origins in private armed militia are sacred – therefore any pragmatic attempt to control arms sales in order to save lives is taboo.

More positively, Durkheim recognized that ‘games and major art forms have emerged from religion and long preserved a religious character’. Certainly, football is a collective ritual – the fans join together, chant the same songs, tattoo the sacred signs of the collective onto their bodies, applaud the players when they kiss the badge, and even, in some inarticulate way, see the team as transcending death. Individuals rise and fall, but as part of Liverpool FC, you’ll never walk alone.

Rock and roll is another modern ritual, a modern means to collective effervescence which arose from religious roots, and ‘every festival, even ones that are purely secular in origin, have certain features of the religious ceremony…Man is transported outside of himself.’ Rock n’ roll is a much less toxic form of collective effervescence than, say, fascism.

I’d suggest that the 2012 Olympics Opening Ceremony brought together all these modern rituals – the celebration of the state, the sacredness of the NHS and the monarchy, the sacredness of sport, and the sacredness of British rock and roll, all orchstrated with rare skill by Danny Boyle and Underworld. But the 2012 Olympics was a one-off for England. A genuine ‘new ritual’ needs to be repeated every few years. Is that possible, in a multicultural megapolis like London or the UK? Have we become too skeptical and rational to let ourselves be carried away en masse? And should politicians be dabbling in the Dionysiac, or is that playing with fire?

More broadly, is society sufficiently transcendent to satisfy our longing for transcendence? I’m not sure it is. I think human consciousness longs for something bigger than just the tribe, and I find Durkheim’s political conception of religion claustrophobic and potentially toxic.

When we immanentize our longing for expanded consciousness, project it onto the state, and yearn for a revolution to heal our pain and boredom, we risk making a false idol of the state. We then make blood-sacrifices to that false god, to try and perpetuate our state of ecstasy. That’s what the Crusades did, it’s what the Nazis did, and it’s what radical Muslims are doing with Islamic State. I’m all for fizz and effervescence, but that moonshine will kill you.