Jade Shepherd has recently completed her PhD on male patients in Victorian Broadmoor at the Queen Mary Centre for the History of the Emotions, and is one of the interviewees in a new Channel 5 series, ‘Inside Broadmoor’. Here she writes about her research, and reflects on the continuing fascination of Broadmoor.

This year marks the 150th anniversary of Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum (now Broadmoor Hospital). Since its establishment, there has been a morbid curiosity towards the asylum and its patients, and there remains considerable public interest today. In the 1940s, members of the public could attend plays put on by Broadmoor’s patients; they sold out every year. This practice has stopped, but in the twenty-first century Steve Hennessy wrote a series of plays about nineteenth and twentieth-century Broadmoor which, by his own account, were extremely popular.[i] Fiction and non-fiction books about the hospital written by Pat McGrath, Simon Winchester, Mark Stevens and Marjorie Wallace also remain popular and feed public demand for stories involving crime, insanity and Broadmoor.[ii] There is also scholarly interest in Broadmoor. A number of publications, written almost exclusively by former psychiatrists and psychotherapists, have been produced detailing the workings of the institution and the treatment of patients in the twentieth century.[iii] Historian Jonathan Andrews has written about the asylum’s female child-murderers, and my PhD thesis examines the crimes, trials and lives of men in Victorian Broadmoor.[iv]

This year has seen a surge of interest in the hospital, in part because of the recent revelation that during the 1980s the late Jimmy Saville visited and abused patients at the hospital after being granted access to its wards, but also because of its sesquicentennial. I was recently interviewed for ‘Inside Broadmoor’, a two-part documentary airing on Channel 5 exploring the history of the hospital. Afterwards, I had two thoughts: why is there still interest in Broadmoor today, and how and why have representations of the institution changed since the nineteenth century?

As in the nineteenth century when cases involving crime and insanity were widely reported, the twentieth and twenty-first century media have fed popular interest in criminal lunacy cases. In May 2011 a father was acquitted for the murder of his six-month-old daughter after the jury accepted he had been suffering from male post-natal depression. There have also been a number of reported cases of infanticidal mothers. Unlike in the nineteenth century when such cases could end up in Broadmoor,[vii] these men and women are sometimes free to go home. Cases garnering international attention also feed public interest in insanity, murder and crime. The trial of Anders Breivik, the Norwegian man found insane after he massacred sixty-nine youths in 2011, was televised and received extensive press attention. There is some public interest regarding where these people are detained and there remains intrigue towards Broadmoor.

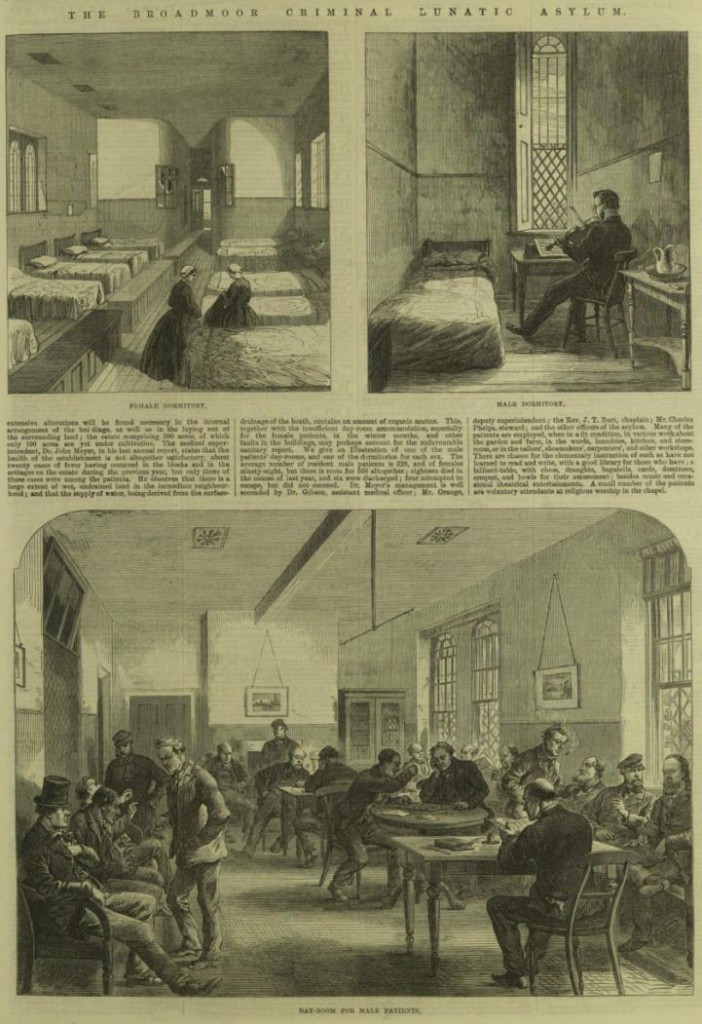

There is arguably a more negative image of Broadmoor in the public imagination today than there was in the nineteenth century when the asylum was the recipient of positive press reports, and when some patients wrote to the press and to their families detailing their comfortable and enjoyable lives in the asylum. In 1867 the Illustrated London News published a complimentary report on the asylum’s regime alongside images of an orderly female dormitory, a male patient playing the violin in his clean, single room, and male patients sitting in a day room enjoying a variety of activities and amusements surrounded by artwork

Today, a cloud of mystery and fear surrounds Broadmoor, with only the scandals and escapes making the headlines, such as that of John Straffen who, in April 1952, escaped and murdered a five-year-old girl.[x] All we know about the hospital today is that it is home to only the most dangerous mentally ill male offenders; those who pose an ongoing threat to society. This is unlike in the nineteenth century when, although Broadmoor was home to primarily murderers, it also held fraudsters and duck thieves, and women as well as men. It might be that the hospital’s population affects how we view it, but it is more likely that the fact we know so little of what goes on inside the institution feeds curiosity and breeds sensation and horror. This was also sometimes the case in the nineteenth century. In 1879, a friend of the wife of one patient expressed her concern to the Superintendent that the woman wanted to visit her husband at the insistence of her ‘pig-headed old mother-in-law’ who had arranged a trip to Broadmoor ‘as a sort of holiday jaunt.’ She could only imagine one reason why she wanted to visit the asylum: ‘I believe the lower classes as a rule like a feast of horrors.’[xi] Indeed, members of the public who knew little or nothing about asylum life were seemingly sometimes judgemental, fearful and disgusted at the thought of Broadmoor. It was viewed ‘in the light of a Bastille […] desecrated by […] popular odium.’[xii] Those familiar with the asylum’s regime, such as staff members, patients’ families, and some patients themselves, sometimes viewed the institution more positively. One patient wrote to his sister:

It is a splendid block of buildings […] pleasantly situated, has an extensive view and is very healthy […] [W]e have three doctors who visit us every day, and the patients spend most of their time […] exercising in the gardens, reading the daily papers, monthly periodicals etc, there is also a well selected library […] a cricket club, billiards, cards and other amusements. In the wintertime we have entertainments given by the patients, such as plays, singing, etc. [We] have a good brass band which gives selections of music every Monday evening during the summer months on the terrace opposite the chapel.

We have good food, plenty of clean clothes, good beds and bedding, and every comfort that one need expect are treat with kindness by the officials placed over us, [and we] have free conversation among the other patients.[xiii]

I suspect that one aim of ‘Inside Broadmoor’ is to question some of the myths surrounding Broadmoor and to debunk any disgust and fear felt towards the hospital. My own research suggests that some of the apparent ill-feeling towards Broadmoor (felt today towards the Victorian asylum and the modern-day hospital) is misplaced: Victorian Broadmoor was not and never has been a prison, it was not necessarily terrifying, its patients were not chained up in cells and left alone, and they did not fear the Superintendent, as has been suggested.[xiv] Rather, as was the case in all Victorian asylums, moral treatment, under which patients were provided with amusements and employment and in which seclusion and restraints were limited or never used, was implemented at Broadmoor.[xv] It was stipulated in the asylum’s Rules that patients had to be treated with ‘kindness and forbearance.’[xvi] By their own accounts some patients enjoyed the activities and occupations provided for them, they made friends and were on good terms with Broadmoor’s staff.[xvii] Some patients openly admitted to enjoying their time at Broadmoor, so much that they readmitted themselves following their release or transfer to a private asylum.[xviii]

Reading the research of Susanne Dell and Graham Robertson, it is possible to gauge some understanding of patients’ experiences in the early 1980s. A comparison of their findings to my own suggests that despite the changing face of Broadmoor and new modes of treatment over the twentieth century, patients’ subjective experiences were similar in both the 1980s and the Victorian period.[xix] Like their nineteenth-century counterparts, some twentieth-century patients said that they enjoyed the educational opportunities afforded to them.[xx] Others valued the companionship of the other patients; some believed they had ‘an easy life’ because they did not have to work and were fed regular meals; and others enjoyed the facilities provided for them, in particular the sport grounds.[xxi] For some, just as in the nineteenth century, Broadmoor was a place of refuge and recovery.[xxii]

Despite the efforts of ‘Inside Broadmoor’ and its vast array of contributors (historians, psychiatrists, authors, archivists and actors) it seems unlikely that any more light will be shed on recent and current hospital life any time soon. The West London Mental Health Trust, under which Broadmoor is run, has closed access to many records concerning the asylum after the nineteenth century (and many records from the nineteenth century). We know very little, for instance, about Broadmoor between 1900 and the First World War or about modern-day hospital life. Of course, we can access the published official reports from the hospital, and the accounts of Ronald Rae Mowat, Murray Cox, Susanne Dell and Graham Roberston on the crimes, treatment and experiences of some patients in the mid-late twentieth century are invaluable, but the intricate details of the lives of the staff and patients inside Broadmoor’s walls, particularly in the twenty-first century, remain a mystery. I imagine this mystery will continue to feed popular and scholarly interest in Broadmoor for many years to come.

[i] Steve Hennessy, Lullabies of Broadmoor: A Broadmoor Quartet (London: Oberon Books, 2011).

[ii] Marjorie Wallace, The Silent Twins: A Harrowing True Story of Sisters Locked in a Shocking Childhood Pact (Vintage, 1996). Patrick McGrath, whose father was superintendent of Broadmoor in the twentieth century, wrote a novel allegedly based on his experiences growing up at the asylum, Asylum (London: Penguin Books, 1997); Simon Winchester, The Surgeon of Crowthorne: A Tale of Murder, Madness and the Oxford English Dictionary (London: Penguin Books, 1999); Mark Stevens, Broadmoor Revealed: Victorian Crime and the Lunatic Asylum (Barnsley: Pen and Sword Social History, 2013).

[iii] D. A. Black, Broadmoor Interacts: Criminal Insanity Revisited (London: Barry Rose Law Publishers Ltd., 2003); Murray Cox, Shakespeare Comes to Broadmoor: The Actors are Come Hither – the Performance of Tragedy in a Secure Psychiatric Hospital (Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 1992); Susan Dell and Graham Robertson, Sentenced to Hospital: Offenders in Broadmoor (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988); Harvey Gordon, Broadmoor (London: Psychology News Press, 2012); Ronald Rae Mowat, Morbid Jealousy and Murder: A Psychiatric Study of Morbidly Jealous Murderers at Broadmoor (London: Tavistock Publications, 1966. Some patients wrote about their time in twentieth century Broadmoor. John Edward Allen wrote about his escape from the institution, Inside Broadmoor (London: W. H. Allen, 1952). Also, F. P. Thompson, Bound For Broadmoor (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1972) and Back From Broadmoor (London: Mowbrays, 1974); Warmark, Guilty but Insane: A Broadmoor Autobiography (London: Chapman and Hall, 1939).

[iv] Jonathan Andrews, ‘The Boundaries of Her Majesty’s Pleasure: Discharging Child-Murderers from Broadmoor and Perth Criminal Lunatic Department c. 1860-1920’, in Infanticide: Historical Perspectives on Child Murder and Concealment, 1550-2000, ed. by Mark Jackson (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, 2002), pp. 216-48. For the construction of Broadmoor, Deborah Weiner, ‘“This Coy and Secluded Dwelling”: Broadmoor Asylum for the Criminally Insane’, in Madness, Architecture and the Built Environment, ed. by Leslie Topp, James E. Moran and Jonathan Andrews (New York and London: Routledge, 2007), pp. 131-148.

[vii] Jade Shepherd, ‘“One of the best fathers until he went out of his mind”: Paternal Child-Murder, 1864-1900’, Journal of Victorian Culture, 18:1 (2013), 17-35.

[viii] http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/breivik-to-dispute-insane-ruling-7619305.html [accessed 17 September 2013].

[ix] ‘The Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum’, Illustrated London News, 24 August 1867, p. 208.

[x] ‘Obituary: John Straffen’, http://www.theguardian.com/news/2007/nov/22/guardianobituaries.obituaries [accessed 25 September 2013]

[xi] BRO, D/H14/D2/2/1/918/17, letter to William Orange.

[xii] W. D. Hood quoted in David Nicolson, ‘A Chapter in the History of Criminal Lunacy in England’, Journal of Mental Science, 23 (July 1877), 165-185 (p. 176).

[xiii] BRO, D/H14/D2/2/1/1116, letter, 10 August 1883.

[xiv] Simon Winchester, The Surgeon of Crowthorne: A Tale of Murder, Madness and the Oxford English Dictionary (London: Penguin Books, 1999), p. 105.

[xv] William Orange, Reports of the Superintendent and Chaplain of Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum for the Year 1873 (London: George E. Eyre and William Spottiswoode, 1874), pp. 2-3.

[xvi] Rules for the Guidance of Officers, Attendants, and Servants of Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum (London: Ford and Tilt, 1869), p. 3.

[xvii] For example, BRO, D/H14/D2/2/1/975/30, memorandum; D/H14/D2/2/1/729/5, letter to William Orange; D/H14/D2/2/1/975/13, letter to William Orange.

[xviii] For example see the case of John Wendover, D/H14/D2/2/1/1074.

[xix] For the treatment of patients in the twentieth century, Black, Broadmoor, p. 127; Gordon, Broadmoor, p. 148.

[xx] Victorian patients were taught how to read and write. In the twentieth century, patients could take GCSES, A Levels and Degrees.

[xxi] Dell and Robertson, Sentenced, p. 39.

[xxii] Ibid., pp. 32. 39. 96.

I know of someone who was let out of broad moor in the mid sevenths only to murder again in shrewsbury

I really enjoyed the two programs about Broadmoor and hope you will be able to make more programs about this type of hospital. Mental health problems are still seen as a taboo subject and I feel the more we know about this the better informed we are and the subject will loose it’s stigma. Mental illness can happen to anyone, for many different reasons and I’d like to know more about this subject.

Pingback: Love, Pain, Ecstasy, and Murder: An Emotional Christmas | The History of Emotions Blog