Dr Alexandra Shepard is Reader in Early Modern History and Director of the Centre for Gender History at the University of Glasgow. Here she reflects on a rare glimpse of a long term friendship between two London women in the early-eighteenth century. She will be discussing this case at greater length in a public lecture for the Royal Historical Society in Huddersfield on 21 October 2014.

Dr Alexandra Shepard is Reader in Early Modern History and Director of the Centre for Gender History at the University of Glasgow. Here she reflects on a rare glimpse of a long term friendship between two London women in the early-eighteenth century. She will be discussing this case at greater length in a public lecture for the Royal Historical Society in Huddersfield on 21 October 2014.

__________

Friendship was celebrated in print in sixteenth and seventeenth century Europe as equivalent to marriage and kinship. One character sketch of a ‘true friend’ depicted him as ‘dear as a good wife, more dear than a brother’. Friends were mates, second selves, and other halves. With roots in classical literature (particularly Cicero’s dialogue On Friendship), such idealisations of ‘entire’ or ‘perfect’ friendship usually imagined relationships between men. In practice, the development of deep emotional attachments was not limited to men. Women also celebrated such bonds using the imagery of both marriage and kinship. The physical remains of such friendships – diaries, letters, and even tombs celebrating their union – tend to survive only for those wealthy enough to have had the time, writing skills and resources to record and commemorate them.

Monument to Sir John Finch and Sir Thomas Baines, in Christ’s College, Cambridge, designed to commemorate their friendship which Finch described as a ‘marriage of souls’.

Such bonds were not exclusive to higher ranking men and women, however. Occasionally the daily realities of past intimacies can be glimpsed amongst the voluminous records of the litigation that soared to unprecedented levels between the mid-sixteenth and mid-eighteenth centuries, which concerned the affairs of the relatively humble as well as the intrigues of the rich. A particularly interesting example concerns the relationship of two women – Elizabeth Carter and Elizabeth Hatchett – who were friends and partners in a pawn-broking business in London in the early eighteenth century. We know about them because of a property dispute over Elizabeth Hatchett’s claims to Elizabeth Carter’s goods after she died ‘of a fever’ in 1722. Hatchett’s own death occurred a mere nine months after Carter’s, and the case was brought by Elizabeth Carter’s sister (Mary Lucas) against one Eleanor Jennings who had inherited Elizabeth Hatchett’s property. Mary Lucas sued Eleanor Jennings on the grounds that Elizabeth Hatchett had wrongfully bequeathed property belonging to Elizabeth Carter (particularly a ‘gold striking watch’ and a brooch of diamonds) to which Hatchett had had no claim and which rightfully belonged to Lucas.

The case revolved around the relationship between Elizabeth Carter and Elizabeth Hatchett who had clearly enjoyed a long association as co-residents and trading partners before Carter’s death. In question was whether they had been mutually bound to each other by intimacy and friendship, or whether they had been in each other’s service and/or debt with one taking responsibility for the other’s maintenance. Thirty-nine witnesses were produced to give evidence, generating over 200 pages of testimony on the character of Carter and Hatchett’s association. In support of Mary Lucas’s case against Eleanor Jennings, Carter was represented by the majority of witnesses as an extremely wealthy and successful midwife as well as money-lender, on whom Hatchett had depended as a servant, and whose extensive goods Hatchett had misappropriated during Carter’s final sickness and after her death. The evidence in support of Eleanor Jennings’ claims instead focused on the extent to which the women had worked in partnership with each other – with Hatchett as the senior partner – and stressed Carter’s relative poverty and her reliance on Hatchett for her basic provisions and care in her final sickness.

It is particularly interesting that both women were married during the majority of their association. Elizabeth Carter’s husband (a baker by trade) predeceased her by a year or so, while Elizabeth Hatchett’s husband outlived her. The women’s ties to each other appear to have been more significant than the bonds of marriage. Hatchett’s husband had been a long-term inmate of Wood Street debtors’ prison until she secured his release (shortly after Carter’s death), reportedly providing him with a new suit of clothes on condition that he relinquished any claims on her property. Elizabeth Carter’s husband had given up baking, and, depending on which witnesses are to believed, either lived comfortably on the proceeds or relied on his wife for support having failed miserably in his trade. At this point the women are described as having ‘a greater Love & kindness to & for each other than one Sister could have for another’. Another witness, declaring that ‘she never saw more sincere Friendship & Affection between any two Persons’, described a scene in which Carter and Hatchett made an agreement that the ‘longer liver’ of the two would inherit all that the other had in her possession, with Carter reassuring her husband that Hatchett would care for him should he be left a widower on her death. Their business partnership – which delivered extensive returns – as well as their emotional ties, appear to have bound these women more closely together than their conjugal obligations to their husbands.

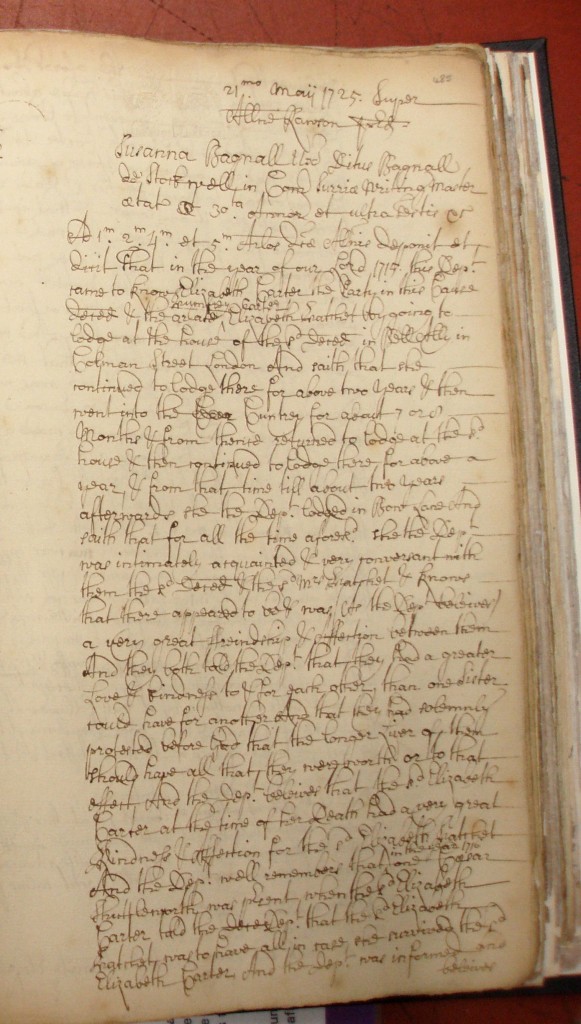

Deposition of Susanna Bagnall, wife of Ditus Bagnall (writing master) of Stockwell, Surrey, 21 May 1725.

Women such as Carter and Hatchett could be lifelines to others – such as Carter’s sister-in-law who borrowed 20 shillings to fit out her son for an apprenticeship (secured with a pawn of a silver salt and a silver spoon). They also contributed crucial resources in the form of cash and credit to an expanding economy. This is not to become dewy eyed about the possibilities of friendship in a bygone age. It is clear from the witness testimony in this case that Carter and Hatchett could drive a hard bargain, and that they were on the look-out for investment opportunities rather than simply providing a service for their friends and neighbours. And just as the authors of printed tracts on friendship cautioned – even of ‘entire’ or ‘perfect’ unions – friendship was not without its risks or pitfalls, particularly when it concerned ties of debt or uneven obligation. Warning his son about trusting a friend with credit, William Cecil (Elizabeth I’s famous adviser) counselled that ‘it is a mere folly for a man to enthrall himself to his friend’. Even the rosiest idealisations of friendship acknowledged the difficulties of disentangling selfless love from instrumental self-interest.

The reason we know so much about of Carter and Hatchett’s great affection for each other was because it did not last: Mary Lucas’s claim to her sister’s estate was at least partly on the grounds that Carter had renounced Hatchett as a thief, a cheat and a fraud not long before her death. The two women had clearly fallen out, with Carter pursuing a charge of theft against Hatchett in a case heard by the Old Bailey in April 1719 – which charge was dropped on the suspicion that it was maliciously motivated rather than grounded in fact.This case not only sheds light on the ‘great intimacy & friendship’ between these two women. It also reveals the dense networks of mutual support that connected Carter and Hatchett with others.

The majority of the witnesses in this case were women, many of whom spoke of their own ‘acquaintance’ and ‘intimacy’ with Carter and Hatchett on account of having regularly borrowed money from them. Because there was insufficient coinage in circulation to support the growing volume of exchange in the early modern economy, as many as 90 per cent of transactions were undertaken on credit. The extension of credit required mutual knowledge and mutual trust, and a good deal of small-scale, informal credit was brokered by wives despite the fact that marriage barred women from the formal ownership of moveable property. Women were also active as money lenders, providing the resources necessary to bridge gaps in cash flow or for future investment. Carter and Hatchett lent money to women from within the immediate vicinity of St Stephen, Coleman Street where they lived as well as to residents of neighbouring parishes. Carter also exploited her connections more further afield, for example in the parish of Christ Church, Surrey, by lending to a poor widow of that parish who got her living by cutting wool for a hatter who had first been introduced to Carter through a mutual friend. Many witnesses describing how they came to borrow money from Carter or Hatchett similarly alluded to webs of friendship that had secured an introduction. In some cases, familial ties established patterns of trust. A neighbour of the two women described how his mother had first borrowed the sum of £10 from Hatchett, after which he and his brother had regularly borrowed smaller amounts, presumably on their mother’s recommendation.

The fragility of the ties binding Carter and Hatchett compared with the legal bonds enshrined in marital property law also become evident in the action of Carter’s husband, Humphrey, who exploited the rift between his wife and Hatchett to claim his entitlement to all outstanding loans due to Carter (which he did by way of a newspaper notice). Carter and Hatchett’s friendship would have chimed with their contemporaries’ concerns about the conflicting demands of selfless devotion and the practical realities of mutual obligations. As recounted by those who witnessed it – no doubt with a degree of distortion to serve the interests of the litigants in the case – Carter and Hatchett’s friendship was perhaps more unusual in traversing the full extremes of both. Besides shedding light on the connection between two women in eighteenth-century London, this case is also a reminder that both extremes were so readily imaginable for the many witnesses who supplied so many intricate details of their relationship.

Further Reading:

Alan Bray, The Friend (University of Chicago Press, 2003)

Amy Louise Erickson, ‘Coverture and capitalism’, History Workshop Journal, 59 (Spring, 2005), pp. 1-16

Alexandra Shepard, Accounting for Oneself: Worth, Credit and the Social Order in Early Modern England (forthcoming, Oxford University Press, 2014)

Return to: Five Hundred Years of Friendship at the History of Emotions Blog