There has been a series of fear-related British news stories during the last week.

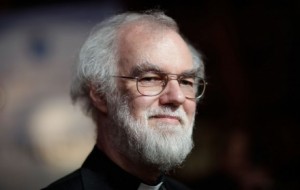

Rowan Williams: "Government badly needs to hear just how much plain fear there is around such questions"

First there was the Archbishop of Canterbury, in an editorial for the New Statesman, warning the coalition government about the effects of their policies in such areas as education and youth services: ‘Government badly needs to hear just how much plain fear there is around such questions at present.’

Rowan Williams seems to want present-day politicians to tell voters not so much ‘I feel your pain’ as ‘I feel your fear’. But what work can the feeling of fear really do in any political argument? It has been notoriously misused by politicians in the past, more than any other emotion, to whip up suspicion, even hatred, of minority groups and immigrants.

Clearly aware of fear’s dodgy past as a political emotion, Williams adds an evasive rider: ‘To acknowledge the reality of fear is not necessarily to collude with it. But not to recognise how pervasive it is risks making it worse.’ In case there were any doubt as to whether the Archbishop really thinks that the goal of government is to manage the population’s emotions, he ends his piece with a vision of a better kind of democracy in which the key question about any policy would be whether it equips people to ‘engage generously’ with their community to build resourcefulness and ‘well-being’.

Then a few days later came another two newsworthy occurrences of fear. The Today Programme, on Monday morning, featured an interview with the dashing octogenarian racing driver, Sir Stirling Moss, announcing his retirement from competitive driving. The 81-year-old explained to John Humphrys how an unexpected feeling had come over him while driving his Porsche in a qualifying session at Le Mans over the weekend: ‘If I go as fast as I need to go, then I’m going to be scared; and I don’t want to be frightened’. Moss said this was the first time he’d felt fear behind the wheel of a racing car and he instantly decided to retire from competitive racing, getting out of the car and walking away at the end of that very lap.

This wonderful story put me in mind of the ancient Stoics. Not only does Moss’s previous imperviousness to fear capture the Stoic ideal of mental calmness and freedom from all the troubling passions of the soul. His sudden and unhesitating decision to put an end to his career recalls the similarly final and immediate decisions taken by some of the great Stoic philosophers of ancient Greece to end not just their careers, but their lives. It was said, for instance, that the founder of the Stoic school, Zeno, lived to the age of 98 (or in some accounts 89, or in others 72) before interpreting a wound on his thumb (or his finger, or his toe) as a warning that it was time for him to depart and committing suicide on the spot.

The Stoics acknowledged that it was better to be healthy than ill, but ultimately they taught that it was not necessarily better to be alive than dead, especially if staying alive meant a loss of rationality and autonomy. It was for this reason that suicide was a common end for the true Stoic in the ancient world, and for this reason that Christians, despite sharing many moral ideals with the Stoics, always treated them with suspicion.

And it was the modern version of this ancient debate between Stoics and Christians which formed the background to the final appearance of fear in the news this week. Sir Terry Pratchett presented a controversial BBC television documentary about the final moments of a 71-year-old man suffering from motor neurone disease who had travelled to the famous Dignitas clinic in Switzerland to end his life by assisted suicide. Individuals who decide to die this way may be considered courageous, even fearless. But disability campaigner Liz Carr’s response was to say that she and other disabled older and terminally ill people are ‘quite fearful’ of what legalising assisted suicide would mean in terms of making vulnerable people feel pressured to ask for their lives to be ended. And so we are back with Rowan Williams’s suggestion: the fear felt by the vulnerable should alter public policy.

There are many possible moral, political, and religious reactions to fear. Most would agree that freedom from fear is one of the most valuable kinds of freedom, and one of the hardest to attain. While differing drastically in their attitudes to suicide, Christians and Stoics have always shared this aspiration to be free from fear. While the Stoic sage achieves it by letting go of their attachment to material goods and even to life itself, the Christian believer is encouraged to trust that there is a greater good beyond everything, even in the face of pain, injustice and death.

One of the phrases most frequently attributed to Jesus in the gospels is ‘Be not afraid’. Someone should tell Rowan Williams.

Thomas Dixon

On ancient philosophy and the modern debate over assisted suicide – the organization that campaigned to have assisted suicide legalized in the US was originally called the Hemlock Society, after the poison Socrates took to end his life. However, Socrates actually speaks against suicide, arguing that because the gods gave us life, its not ours to take away.

There’s this paradox in the Stoics’ attitude to suicide – on the one hand, their entire philosophy is about accepting the will of the universe. On the other hand, they withhold the right at any moment to go ‘sod this’ and end it all. Suicide could seem to be the ultimate refusal to accept given circumstances….

IN any case, the Stoics’ attitude to death is quite fitting with the baby boomer ethos. Seneca wrote: ‘Just as I shall select my ship when I am about to go on a voyage, or my house when I propose to take a residence, so I shall choose my death when I am about to depart from life. ‘ Its death as the ultimate lifestyle choice.

Pingback: Suicide and the law: Stoics versus Christians | The History of Emotions Blog