Sally Holloway was one of the speakers at our series of Lunchtime Seminars at Queen Mary during 2010-11. Her PhD research at Royal Holloway, University of London, explores the role of material objects in eighteenth-century love and courtship. In this post, she reflects on the ways that expressions of love and desire, today conveyed via text messages or social networking sites, were once embodied in more tangible physical form. Sally writes:

When eighteenth-century suitors embarked on the search for a spouse, they entered into a world of emotionally-invested objects such as ribbons, rings, hair-work bracelets and portrait miniatures. When given as a gift, these objects acted as an embodiment of a suitor’s intentions, providing an important form of language and socially recognised custom. As the ballad ‘Faint Heart never won fair Lady’ wisely advised c. 1682-92:

Win her with Fairings and sweetening Treats,

Lasses are soonest o’ercome this way;

Ribbons and Rings will work most strange feats,

and bring you into favour and play.

The purpose of these gifts was to conduct vulnerable parties through the process of courtship, from its early stages to a formal betrothal, culminating in a church wedding. The affection and obligation represented by gifts meant that they could be summoned in court as evidence of commitment in contract or spousal litigation and ‘breach of promise’ suits, demonstrating the important role they played in embodying emotional ties.

Objects such as silhouettes and portrait miniatures provided couples with a constant reminder of one another’s image, encouraging them to regularly gaze at each other during their separation. William Ward’s mezzotint ‘The Pledge of Love’ (1788) depicts a young woman seated beneath a tree, holding a love letter in her hand. She is completely absorbed in the process of looking at a miniature suspended on a ribbon around her neck. The inscription reads,

The lovely Fair with rapture views

This token of their love

Then all her promises renews

And hopes he’ll constant prove.

Individuals thus directed their romantic longing towards representations of loved ones, demonstrating the cultural importance given to gazing at objects sent by lovers. Gifts such as scent bottles were inscribed with messages reading ‘Think of Me’ to encourage lovers to gaze at tokens while thinking about their relationship, whilst others were painted with phrases such as ‘Who opens this, Must have a Kiss’ and ‘Esteem the Giver,’ demonstrating the role of objects in encouraging the development of intimacy.

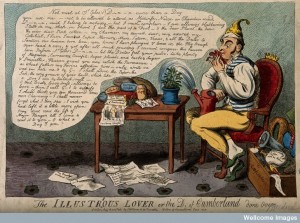

Physically handling objects was a further crucial stage in fostering the development of love, encouraging intimacy through the sense of touch. As the French materialist Georges Buffon (1707-1788) argued in his Natural history, general and particular (1780), if humans ‘are desirous of knowing ourselves, we must cultivate this sense, by which alone we are enabled to form a dispassionate judgment concerning our nature and condition.’ The ritualised process of touching gifts is satirised in Isaac Cruikshank’s ‘The Illustrious Lover’ (1804), where the Duke of Cumberland isolates himself with a wide collection of tokens to celebrate his love for Mrs. Powell. He holds a red cotton ribbon to his mouth, enjoying the transporting properties of its texture and smell. The print underlines the agency of objects as sites of emotion, emphasising the central role played by touching gifts in the development of romantic love.

Isaac Cruikshank's ‘The Illustrious Lover' (1804) suggested the level of emotional arousal that a love token might excite

This brief analysis of the rituals surrounding love tokens demonstrates the inherent possibilities offered by a material history of emotion. Such histories reveal practices which would otherwise remain unknown to us, taking the history of the emotions below the level of literacy. When studying courtship, these practices include the gazing at and touching of gifts, which were fundamental in shaping the experience of romantic love for eighteenth-century suitors.

Sally Holloway

Thank you – really enjoyed that.

Pingback: What is the history of emotions? Part III | The History of Emotions Blog