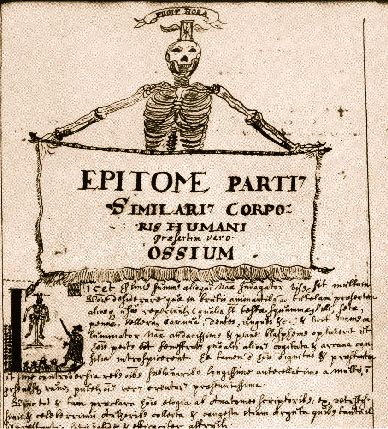

In 1672, a young anatomy student named Alexander Flint began doodling in his notebook (above) as his lecturer, James Pillans, droned on about the anatomical structures of the human body. In a small picture to the left of Flint’s notes appears the skeletal remains of some unfortunate soul—perhaps an executed criminal—who has in death become the object of this anatomist’s weekly lesson.

But the most interesting sketch looms above Flint’s notes, at the top of the page. It is the skeleton—not as a medical subject but as Death—with the words ‘fugit hora’ (literally, ‘the hours flee’). The skeleton may be anatomically incorrect—but these flaws are forgivable in a student who has only just begun his surgical career. In fact, it is likely because of Flint’s inexperience with the dead that we see these ‘memento mori’ (‘reminders of death’) plastered all over his early notes. He is not yet emotionally immune to the sight of dead bodies in the dissection theatre. [1]

Today, we call this ‘clinical detachment’, a term which historian Ruth Richardson points out is ‘less emotive, more scientific’. [2] It is not the by-product of a medical education; it is the goal. Those who are clinically detached are ‘objective’. They are unmoved by the sight, smell and sounds of the human body, and are therefore ‘above prejudice’ when examining it. But reaching this stage is a process, and the outcome is not guaranteed. A physician currently practising medicine in the UK remembers:

Dissecting earthworms in biology was no preparation. . . . One of the students was unable to sit through the introductory lecture, which was about scalpels and forceps, and fat and fascia, because of the thought of dissecting. And the first week that we were in the dissecting room he spent throwing up in the loo. At the end of the first week he blew his brains out with a shotgun. [3]

Although an extreme example, this story serves to remind us that revulsion, disgust and horror are all natural responses to the process of dissection. Only through constant exposure to dead bodies do medical practitioners become ‘clinically detached’.

The term ‘clinical detachment’ may be a modern one, but the concept is not new. The 18th-century surgeon and anatomist, William Hunter (right), often remarked to his students: ‘Anatomy is the Basis of Surgery, it informs the Head, guides the hand, and familiarizes the heart to a kind of necessary Inhumanity’. [4]

The term ‘clinical detachment’ may be a modern one, but the concept is not new. The 18th-century surgeon and anatomist, William Hunter (right), often remarked to his students: ‘Anatomy is the Basis of Surgery, it informs the Head, guides the hand, and familiarizes the heart to a kind of necessary Inhumanity’. [4]

But what exactly did Hunter mean by a ‘necessary inhumanity’? And why did Hunter believe it was important that students cultivate this trait?

Before the discovery of anaesthetics in the 19th century, surgery was a brutal affair. The patient had to be restrained during an operation; the pain might be so great that he or she would pass out. Dangerous amounts of blood could be lost. The risk of dying was high; the risk of infection was even higher. The surgeon was so feared that in many cases, patients waited until it was too late before approaching one for help.

Dead bodies, on the other hand, could not scream out in agony, nor would they bleed when sliced open. In this way, the novice could learn how to remove a bladder stone or amputate a gangrenous arm at his own leisure, observing the anatomical structures of the human body as he went along. Ultimately, this prepared the student to operate on the living. The French anatomist, Joseph-Guichard Duverney (1648-1730), remarked that by ‘seeing and practising’ on dead bodies, ‘we loose foolish tenderness, so we can hear them cry, with out any disorder’. [5] In other words, the surgeon gained a ‘necessary inhumanity’ through the act of dissection.

Of course, this required the novice to overcome the realities of dissection first. Even today, dissecting a human body is a dirty business. Druin Burch, author of Digging up the Dead, remembers his experiences from medical school:

Modern corpses are preserved in formalin, and the smell never quite left my hands at the end of the day…although we took care to dispose of the human parts properly, cutting someone up proved to be a messy occupation. I got half used to finding bits of fat and connective tissue later in the day, trodden onto the sole of my shoe or hitching a ride in a fold of my jeans. It made no emotional or practical sense to treat such unpleasant surprises with any sacred reverence. A half-preserved and half-rotten piece of fat trodden into the carpet cries out for no formal burial. [6]

Yet for all its ‘messiness’, dissection today is still radically different from how it was in the past. The pickled corpses, the metal gurneys, the crisp white sheets: all of this serves to dehumanise the process, and to create uniformity and regularity where it would otherwise not exist.

For these reasons, it is likely that it was more difficult in the past to remove oneself emotionally from the act of dissection. Students often complained about the ‘putrid stenches’ emanating from rotting corpses. These were not the sterilised bodies of today—with their frozen limbs and starched linens. These were bodies often plucked from the grave, two or three days in the ground. They were in semi or even advanced stages of decomposition. They were bloated and rotten. There was nothing clinical or sterile about this experience.

Ultimately, however, students began to view the body not as a human but as an anatomical specimen. Some became so detached that they were able to cut open the bodies of relatives, as in the case of William Harvey, who dissected both his father and his sister in the 16th century. This, of course, was highly unusual, but it does illustrate the extent to which a surgeon or anatomist could remove himself from the horrible realty stretched out before him.

In a post-anaesthetic world, the ‘desensitisation’ of medical students to the human body raises new concerns. ‘Clinical detachment’ may help students through the messy business of dissection, but is it necessarily a good trait to carry on into practice? After all, a patient is not a cadaver: he or she is a living, breathing human being who experiences a wide array of emotions and physical sensations. One physician recently remarked:

I found myself looking at the body as a wonderful machine, but not as a creature with a soul—that worried me a bit. What in fact I had to do was consciously unlearn that sort of thing, and start to look at human beings as human beings. [7]

Of course, what has been done cannot easily be undone. And perhaps shouldn’t be.

Lindsey Fitzharris is currently a Wellcome Trust Research Fellow in the History Department at QMUL. Her website, The Chirurgeon’s Apprentice, focuses on the history of pre-anaesthetic surgery. For more, click here.

1. Edinburgh University, MS Dc 6.4. Originally discussed in Ruth Richardson, Death, Dissection and the Destitute (1987), p. 31.

2. Ruth Richardson, ‘A Necessary Inhumanity?’, Journal of Medical Ethics: Medical Humanities 2000 (26), p. 104.

3. Qtd in Richardson, ‘A Necessary Inhumanity?’, p. 104.

4. William Hunter, Introductory Lecture to Students [c. 1780], St Thomas’s Hospital, MS 55.182.

5. Patrick Mitchell, Lecture Notes taken in Paris mainly from the Lectures of Joseph Guichard Duverney at the Jardin du Roi from 1697-8, Wellcome Library, MS 6.f.134. Originally qtd in Lynda Payne, With Words and Knives: Learning Medical Dispassion in Early Modern England (2007), p. 87.

6. Druin Burch, Digging up the Dead: Uncovering the Life and Times of an Extraordinary Surgeon (2007), p. 51.

7. Qtd in Richardson, ‘A Necessary Inhumanity?’, p. 104.

This is fascinating stuff: the connection of dispassion with scientific knowledge and practice; but also the fear that this kind of detachment can become inhuman. It puts me in mind of late-Victorian debates about vivisection, as well as the idea in the same period that women should never study science and medicine since they would be ‘deflowered’ by this kind of experience. Charles Darwin abandoned his medical studies in Edinburgh in the 1820s, and moved to Cambridge to train as a clergyman, because he couldn’t bear the sight of surgery, especially an operation on a child. One of my favourite Victorian books, The Island of Dr Moreau by H. G. Wells, depicts a man-turned-monster by his own hideous programme of advanced vivisection. If scientific knowledge could only be produced by the repression of human feeling, Wells warned, then atrocities would lie ahead.