After the romantic excesses of February 14 last week, Dr Emily Butterworth of King’s College London, offers some Renaissance advice on how to write about love, inspired by Michel de Montaigne’s essay, ‘On Some Lines of Virgil’ (1588-1592).

A frank meditation on contemporary attitudes to sex and his own reading practices, Montaigne’s essay focuses on erotic poetry by Virgil, Lucretius and Ovid as examples and counter-examples of effective writing. Poetry is most powerful when it suggests, Montaigne believes, and not when it tells. While the writing that Montaigne condemns is more explicit and even pornographic than most run-of-the-mill Valentine messages, his plea for a suggestive, allusive, half-hidden kind of style might still be a useful corrective to the straightforward declarations that circulate every year. In this passage Montaigne condemns Ovid for excessive explicitness:

But there are certain other things that we hide in order to reveal them. Listen to this poet speaking more openly:

Et nudam pressi corpus ad usque meum. [And I pressed her, naked, against my body]

It feels like he’s gelding me! The poet who reveals everything is cloying and distasteful. The timid poet makes us imagine more, perhaps, than he meant. There’s treason in this kind of modesty, above all in those poets who open such a royal road to the imagination. Both the act and its description should feel like theft.

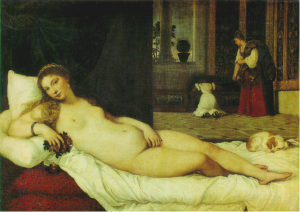

Some things are hidden in order to draw more attention to them: Montaigne’s examples include holy relics and women’s breasts. It’s a gesture that is familiar from art of the period, too. Titian’s Venus of Urbino’s modest gesture draws attention all the more to her nakedness. In the background, two women search through a chest (perhaps the cloak that one of them is holding is to cover the goddess?), echo the theme of hidden pleasures and locked-away treasure.

Here’s a checklist for next year’s declarations, and indeed for declarations of love at any time, inspired by Montaigne:

- Concealment and disguise are a game, and in fact a form of revelation: sexual desire is a thing best revealed through concealment

- Discretion is more compelling than plain speaking, and more effective

- Avoid castrating your reader with excessive frankness: you don’t want to extinguish his desire

- Lead your reader on; seduce him; make him betray himself

- Be prepared to risk yourself and betray your own desire