Dr Stephanie Downes is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Melbourne, where she is part of the ARC Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions. In Australia, Peter Carey’s new novel has just been published. It is due out in the UK next month. In this guest post, Stephanie reviews the book for the History of Emotions Blog.

The title of Peter Carey’s new novel, The Chemistry of Tears, practically begs to be (over-)analysed. Scientific rationalism alongside passionate emotionality; the manufactured and the organic; the brain and the heart. On the cover of the Australian edition is printed part of John Singer Sargent’s portrait of Lady Agnew of Lochnaw, with a close up of her mouth. So blown-up is the image that what we see are not the brushstrokes of the artist but the digitized pixels of the copy. The title itself is printed in cutouts which suggest that beneath the woman’s pixilated skin are the cogs and wheels of a machine. Layer upon layer, the novel offers its own portrait of a woman in pieces in the twenty-first century, and the role played by technologies in our emotional lives.

The title doesn’t focus, however, on any one emotion (say, sadness), or even on the physical sign of that emotion (say, crying), but on a material manifestation: tears, both as objects, and as subject of analysis, too. How they ‘work’ and what they represent. Since the novel is structured as a narrative-in-a-narrative, one in the nineteenth century and the other in the present day, it won’t hurt to evoke Tennyson on the complexity of understanding what it is to cry: ‘Tears, idle tears, I know not what they mean’!

Carey’s titular ‘tears’ might evoke sadness or melancholy, for centuries the subject of scientific investigation. (Lars Von Trier’s recent film, Melancholia, looks back to this history of astrology and bodily humours in the giant planet that threatens Earth’s existence.) The novel, however, is very specific in identifying the source of its protagonist’s tears: Carey’s crying woman has lost a loved one, and his is a portrait of her grief. The central character conforms at various points to the classical motif of the female mourner, complete with wailing (‘I began to howl and could not stop’), renting of clothes (‘I tore my shirt in half, and ripped the sleeves away’), and matting of hair (‘Three trains later I surfaced at Olympia with unwashed hair.’)

Carey has set this new work in a museum, the fictional but curiously familiar Swinburne Museum, ‘one of London’s almost-secret treasure-houses.’ The novel, too, is crammed with objects, which include both the simple – a sock, a lover’s hat, a bottle of vodka – and the structured – a clock, a mechanical animal, a robot, a mobile phone, or ‘Frankenpod’ in Carey-speak. The technological and the human, however, don’t contrast so much as they overlap, and the novel moves around the idea of emotional response as the human machine at its most intricate.

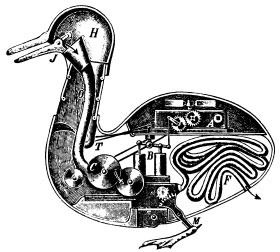

The protagonist, Catherine Gehrig, a specialist in the restoration of clockwork, hears on the opening page of the death of her lover of thirteen years. We learn immediately that the affair was both in-office and extramarital and that Catherine’s mourning, like her love, must be lived in private. When the novel begins the death has already occured. ‘Dead’ is its first word. Dead, too, is the inanimate object which is its central metaphor, a mechanical duck or automaton, which Catherine is charged with repairing. The thing about the duck, however, is that it is insistently lifelike: it eats, flaps its wings, excretes. The bird arrives in pieces – 8 tea chests and 4 wooden boxes – which Catherine reassembles as the novel unfolds.

Interleaved with Catherine’s narrative are letters written by a nineteenth-century Englishman, Henry Brandling, to his dying son. Henry is in the process of commissioning the bird as a gift for his son: to enchant him back to health with sheer delight. His plans for the machine are based on those of the real life eighteenth-century Jacques de Vaucanson’s Canard Digérateur – the Digesting Duck.

That the novel ultimately stretches across at least three centuries and evokes a plethora of cultural associations helps to raise the issue of tears in the present for those of us interested in a history of emotions, and of literary representations of emotions. When do we shed tears in twenty-first century Australia? England? Other parts of the world? And when – and how – do we write about them?

There’s a description of a minor female character crying in the first chapter – ‘bawling,’ Carey puts it repeatedly – ‘her lipstick […] smeared and her mouth folded like an ugly sock.’ A few pages later, Catherine, in the first throes of her grief, takes up the same motif: ‘I bawled and bawled and now I was the one whose mouth became a sock puppet.’ The protagonist seems to imitate the behaviour she’d seen earlier even to the point of evoking the same metaphor. It’s a familiar script to most readers, too, made more familiar still with the intrusion of that crumpled sock. We all cry, we all have crumpled socks, or, at the very least, we know what they look like. Comedy and tragedy, we’re reminded, like laughter and crying, are something alike, especially in contorting mouths.

Catherine’s lost love – what Freud calls, in Mourning and Melancholia, a ‘lost love-object’ – is almost distressingly absent from the novel. On one hand, it is hard to feel Catherine’s grief, because we don’t understand what it is that she has lost. Matthew survives for us as for Catherine only in fragments, objects like his car, a floppy hat, an old email. A colleague happened to pass on a link to a blog post on ‘blobjects’ just as I was getting into Carey’s novel. Rather than words or gestures, ‘Blobjects’ are abstract objects that communicate feeling. How do the real objects in our lives express emotion, or even contain them? How do we remember those we’ve lost, and relate to those who are living?

And what about the duck? Inanimate and unfeeling, it’s also humanized and strangely humanizing. As Carey builds his metaphor, and Catherine rebuilds the machine, it becomes a metaphor of extreme artifice, which turns playfully on any number of clichés associated with the process of grief: rebuilding a life, mending, fixing, picking up the pieces; coping mechanisms. What does the defecating duck wryly hint about human existence? And do the clocks of the novel themselves suggest that ‘time heals all wounds’? I hasten to point out at this juncture that even Catherine herself isn’t immune to such over-analysis of the events in her life. She emails the head curator of horology (Eric ‘Crofty’ – do I hear ‘Crafty,’ here?), who has charged her with the task of repairing the automaton, that it is ‘highly “inappropriate” to give a grieving woman the task of simulating life.’

The medievalist in me wants to go one step further still… The literary landscape of the Middle Ages is littered with crying women, from the Virgin Mary to Margery Kempe. Catherine’s medieval namesake is a saint and a martyr. Surely it’s no accident, with all the clocks and cogs of the novel, that St Catherine was martyred on the wheel? But there is something of the Mary in Carey’s Catherine, too, who is perhaps more ‘Magdalen’ than ‘Virgin.’ Catherine is grieving for a lover with whom she has been having an affair. Hers are tears of grief and, perhaps, of shame (another recent topic on this blog).

And yet, for all this talk of tears, I don’t think Carey’s is a novel about expressing emotions so much as it is about reading them. The novel begins with identical portraits of two women crying. But it also starts with an emotional cue that’s been misread. When Catherine finds the secretary crying at her desk with her mouth like a crumpled sock, she asks her what is wrong. Presumably her sobs muffle her words, because Catherine misunderstands her reply:

‘Oh haven’t you heard? Mr Tindall’s dead.’

What I heard was: ‘Mr Tindall hurt his head.’ I thought, for God’s sake, pull yourself together.

(More women going to pieces in grief.) Is this opening sequence a comment on the interpretation of emotion? We often talk about ‘reading’ emotion of the face of another, and Carey’s novel often documents reading practices in general. First, it presents a narrative within a narrative: as Catherine’s grief unfolds and the mechanical duck is rebuilt she reads Henry’s letters to his son. Inside the letters, the fictional Herr Sumper, charged with building the duck, interprets the plans according to whims of his own. Letters, plans, formulas, faces, and bodies both mechanical and human, all become scripts for various characters to read and attempt to understand, even, to impose understanding on. When Catherine first picks up Henry’s letters, she observes that:

All my feelings were displaced, but it was definitely this peculiar style of handwriting that engaged my tender sympathy, for I had decided that the writer had been driven mad. […] I had no doubt he was a man, and I pitied him before I read a word.

The novel is structured not just by Catherine’s restoration of the duck, or Henry’s account of its commissioning, but Catherine’s experience of reading that account. Some chapters present the letters to us in Henry’s own words (‘Henry’) and others (‘Catherine & Henry’) offer the letters refracted through the protagonist’s own reading of their ‘mechanical handwriting’. The ‘Catherine’ chapters were the ones I found most enjoyable. There was something jarringly metaphysical about the nineteenth-century sections of the novel, too dreamlike, murky, and ambiguous; too open to interpretation; almost too hard to read.

Is it all, by the end, just another device, or piece of literary mechanics? Is Carey’s real target the critic – those who read writers?

One Australian reviewer called the novel ‘profoundly moving’. The cliché doesn’t really inspire the preordering of copies on Amazon in time for the novel’s Easter weekend release in the UK. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, however, many a novel’s success was judged not by copies sold, but by the number of tears its readers shed. To be ‘profoundly moved’ suggests that emotions are deep, but that the act of reading might better connect us with them.

That’s the thing about Vaucanson’s duck, of course: it moves. But does Carey’s?

A reviewer for Melbourne’s The Age praised the novel’s tricks and mechanics, but lamented that ‘not once, curse my metallic heart, did Carey’s intricate mechanical duck actually make me cry.’ I confess, I didn’t cry either. Was I moved, like the first reviewer? I can’t quite recall. But perhaps this confusion is exactly the desired effect. If this is a novel about the reading experience then maybe this displacement from the experience of emotion makes perfect sense. We observe with almost scientific detachment the novel’s portrait of grief, and we recognize that various emotional templates are applied. Tears, idle tears…. The tears in Carey’s novel seem to be working very hard indeed. As Catherine cries over memories of her lover, a character consoles that ‘tears produced by emotions are chemically different from those we need for lubrication. So my shameful little tissues, he said, now contained […] a powerful natural painkiller.’ Catherine winds up (no pun intended) laughing at the same memories.

Tears transform. And the duck moves, all right. Like a well-lubricated machine. But it’s the human body in Carey’s novel, with its signs and sensors, functions and excretions – the body as text and author – that really cries out to be read.

Pingback: Happy Birthday to Us! Top 10 Posts | The History of Emotions Blog

i like what you’ve written, but i’m obsessing over amanda, the oil spill, the apocalyptic prophecies of fuelled transportation and the madness/exhilaration of the articulated automaton. you do not and cannot see what is before you, indeed!

even today, those who fear a future that is already here–cyborgs the lot of us with our frankenpods various–we are overwhelmed with wonder, and completely seduced by technologies about which no one can knowledgably speak in regards to the future of machines/computers, and enslaved to the shiny happy creatures being assembled as i key these words in. there are lots of supporting examples–benz, fixations on webcams and security, the sexualized assembly, the rapturous politicians admitting the trojan swan into the capital, but, alas, too late: the civilization is already gone. and, again, the direct allusions to mary shelley’s mad scientist/technologist of death.

i believe carey has given us an updated parable about what it is to be human, and how we lose that to machines…..

Pingback: Moving Pictures | The History of Emotions Blog