As a historian, the four words in front of me made my heart skip a beat – and not in an ‘our eyes met across a crowded room’ sort of way. Pencilled in the archival catalogue was a note about one of the items in the collections of a Victorian psychiatric hospital: ‘This item contains very disturbing images and is not to be produced’. The item that I had looked at on my last visit was now an object under some scrutiny, and I possibly suspected of possessing a distasteful prurient curiosity.

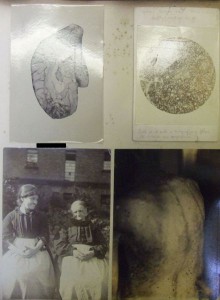

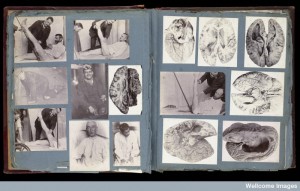

The document in question was a scrapbook of photographs kept by the hospital’s pathological laboratory at the end of the nineteenth century, remarkably similar to that kept at Colney Hatch Asylum (recently discussed by Barbara Brookes in Exhibiting Madness in Museums). The homogeneity of the albums testifies to their importance within the history of psychiatry, with two asylums simultaneously cataloguing pictures of brains at autopsy and cases of physical deformity during life. On one page, the asylum mortuary is draped with black cloth against which a deceased patient is photographed, limbs contorted, their mouth a silent ‘O’. On another, a female patient lies in bed as the hands of a doctor or nurse out of shot hold her frail arm upright. There are pictures of patients in the wards and asylum gardens: a shot of two women seated in the garden in neat dresses and aprons, one smiling meekly at the other. A nude male patient with a skin condition is photographed against an elaborate backdrop of a woodland scene. ‘Dr Boddington’ poses for the camera during a post mortem, the patient’s skull resting on their knees.

A page from the album: brain section, photomicrograph, patients outdoors, a patient's skin condition.

For me, the scrapbook’s usefulness was in highlighting what the asylum’s doctors considered especially worthy of note. Of the 118 photographs in the book, 43 showed a concern for muscular or limbic deformities and the microscopic examination of nerves and muscles (in photomicrographs). As a consequence, my research into masculinity in the asylum took a corporeal turn which proved immensely rich and would not have occurred had I not had the opportunity of examining the scrapbook.

However, I can equally understand that it is a document that could prove as upsetting to some observers as it did fascinating to me. The lack of any explanation of the content gives the book a sense of voyeuristic, morbid curiosity – a fetishistic collecting of patients and their bodies. Jennifer Green-Lewis, author of Framing the Victorians: Photography and the Culture of Realism, emphasises how photographs acted as evidence documenting the natural world. Photographs of people however, especially those in an institutional context, tend to arouse our suspicions. The nineteenth-century images that we are attached to, says Green-Lewis, are those which indulge our romantic idea of ‘how it used to be’: the photographs collected in the scrapbook speak of times and experiences that modern sensibility would much rather forget. As a result, the initial reaction to the pathological laboratory’s album is that it is wrong, sinister, or questionable.

That a photograph possesses the ability to arouse our emotions does not, however, render it irrelevant to the historical record. The presentation of the scrapbook, with its neatly written captions, suggests the importance attached to these particular patients and their conditions, even if we can discern no emotional investment in their staging. Like the subjects of American memorial portraits, they and their bodies were commodified by asylum doctors, not as loved ones wreathed in flowers but as objects of scientific investigation. As disagreeable as it may be to envisage these patients as ‘objects’, the spirit of late nineteenth-century asylum research was intensely driven by the prospect of harnessing the mysteries of the mind and, as in many other areas of science, photography proved an exciting new tool. Many of the patients depicted in the scrapbook were the subject of contemporary journal articles – interesting cases that were seen as having something to contribute to clinical and pathological knowledge of mental illness. One of the most powerful images in the album is a post-mortem photograph of 16 year old George P., who was the subject of an 1890 Journal of Mental Science article, ‘The Morbid Histology of a Case of Syphilitic Epileptic Idiocy’. Reading the article gives his photograph further emotional force as the author describes George’s condition: he smiled and nodded his head when taken notice of (though screamed passionately when physically examined) and was pleased by coloured pictures or playthings such as a bunch of keys. It is notable that despite referring to the photograph in the text of the article (‘Contractures of lower extremities … as depicted in illustration’), the image of George after death was omitted. We can only speculate on the reasons for this – poor image quality, a picture lost in the post, lack of space – but it is impossible not to wonder if George’s picture was considered too harrowing even for readers of the Journal of Mental Science.

Thankfully, the archive that holds the album is aware of its uses for the historian, and calmed my initial panic at that pencilled notation: whilst they would be wary of producing the item to the casual visitor, it is available to those who understand what they might see upon leafing through its pages. ‘It would be a case of reminding the user of the record they had, what to expect and that they may find it upsetting. I’d also advise that they keep the volume in a corner, facing away from other users, and to be mindful that it may upset other people’, one of the archivists told me. Whilst parts of the Colney Hatch album can be viewed by researchers online via Wellcome Images, in a small county archive that is largely utilised by family historians it’s certainly wise to make users aware of the potentially disturbing nature of the items available, some of which may pertain to their own (albeit distant) relatives. It’s easy to become slightly blind to the impact of medical images when seeing them on an almost daily basis as part of our research, and reminding ourselves of the very real people depicted in them doesn’t necessarily detract from their historical value. These were, as the archivist observed, ‘all real people who once had families and a whole life of their own. [We] have to respect their memory and the life they led’.

Jennifer Wallis

Hello Ms. Wallis,

I am very interested in this Colney Hatch photo scrapbook. Can you tell me which archive has it and whether it is accessible for public viewing?

Thank you very much.

Robert House

Hi Robert,

Thanks for your comment – the album is held by the Wellcome Library in London and there are several pages from it that have been scanned and can be viewed online. You can view the catalogue record, and images, here: http://catalogue.wellcome.ac.uk/record=b1175302. I shouldn’t imagine there would be any problem viewing it if you have a Wellcome Library membership (and if you haven’t already, getting one is a simple process).

All best,

Jen.

Hi Jen,

Fascinating blog piece, thank you! I’m doing a masters dissertation looking into photography and mental disorders, and was wondering where this scrapbook you’ve found is located or if you’ve found many other similar scrapbooks or casenotes with many photos over the course of your research? If it’s not too much bother for you to tell me!

Many thanks,

Katy

Fascinating Jen. I look forward to reading more of your work.

Best wishes,

Barbara Brookes