In 1859 Charles Darwin, musing on the way insects transform their appearance to fit in with their surroundings, asked: “why, to the perplexity of naturalists, has Nature condescended to the tricks of the stage?” Yet nature condescends to theatrical tricks among humans too. Our compulsion to mimic each other’s postures, gestures and facial expressions – to catch each other’s yawns, sway in time with tightrope walkers, or strain while watching an athlete – has proved a puzzle which continues to intrigue psychologists and physiologists. For Victorian men of science, mimicry was frequently regarded as deviant and pathological: among the “feeble- minded”, women and “the lower races, a tendency to imitation is a very constant peculiarity,” wrote George J Romanes in 1883.

However, by the beginning of the 20th century, involuntary copying was increasingly understood to be a key psychological mechanism, responsible for learning, socialisation, empathy and even morality. Since the discovery of ‘mirror neurons’ in 1994, the idea that our bodies helplessly echo each other now extends to the operations of the brain itself, sparking vigorous debates in neuroscience and beyond about a new era of human interconnectedness. An enduring problem associated with the idea that we are, to quote the psychologist James Sully, mere “copying machines” is the unsettling connection between mimicry and theatricality. It is no coincidence that Darwin, writing about shape- shifting butterflies, complained of their theatricality: such insects refuse to be pigeonholed, confounding the lepidopterist’s neat categories. Both theatre and mimicry conventionally evoke slippery insincerity and superficiality, undermining notions of a secure identity and raising the unnerving possibility that we are not entirely in possession of ourselves.

My current research charts the collision of theatre and medicine in the cultural history of involuntary mimicry. Theatre appears as a leading metaphor in scientific writing on motor mimicry from the 1850s onwards. Moreover, in filmic and literary treatments of the phenomenon, alarming involuntary copying is also often entangled with theatre and its vicissitudes. In H G Wells’s short tale ‘The Sad Story of a Dramatic Critic’ (1894), for example, the hero cannot help replicating the histrionic attitudes he witnesses nightly in the theatre. In an “infection of sympathetic imitation”, he is forced to perform “agonising yelps, lip- gnawings, glaring horrors” and so on, leaving him with the alarming feeling of being “obliterated”. While for Wells imitation festers in the auditorium, the protagonist of Woody Allen’s 1983 film Zelig, a man compelled to transform his appearance to replicate whichever person or object is closest to him, becomes a theatrical attraction (before becoming demonised amid a national panic about infiltration).

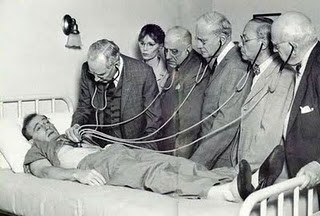

While images of theatricality conventionally harbour anxieties surrounding involuntary mimicry – it obliterates selfhood, it threatens borders – theatre and performance have also been a key part of the scientific study of imitation. We might expect to find rotary event recorders, video cameras and fMRI scanners among the technologies associated with the experimental history of motor mimicry, but it is a surprise to discover that scientists have also entered theatrical environments (from séances to sporting matches), used theatrical techniques (from acting and directing to the creation of emotional audiences) and encountered theatrical problems (from overacting and embarrassment to forgotten lines) in their efforts to provoke, scrutinise and measure involuntary imitation.

In 1872, Darwin observed that at leaping matches, “as the performer makes his spring, many of the spectators, generally men and boys, move their feet”. Two decades later, in Sully’s studies of children, the nursery was repeatedly turned into a tiny theatre when the psychologist pretended to laugh and cry, all the while observing the response of his infant audiences. In 1933, Clark Hull reported making his laboratory assistant Miss H into an actress: while she pretended to carry out tests, all the while swaying back and forth, Hull surreptitiously attached a rotary event recorder to the unwitting subject’s clothes with string and measured any imitative swaying that ensued. In 1986, a group of researchers in Australia became performers themselves, enacting scrupulously choreographed routines in the laboratory, and filming their audiences’ responses (Bavelas, Black, Lemery and Mullett, 1986).

The performativity of experimentation has been has been highlighted by philosophers of science, including Robert Crease (1993) and Andrew Pickering (1995), yet the more problematic world of theatre also provides a suggestive lens through which to chart the embodied and emotional texture of modern laboratory life. While Darwin complained that the theatrical deceptions of mimicry seemed to mock or evade the scientific quest for knowledge, the modern history of motor mimicry is intimately tied to the ‘tricks of the stage’. Theatre’s slippages between seeming and being have historically expressed all that is unnerving about the possibility that we are mere ‘copying machines’; conversely, misdirection, sleight of hand, pretence and dissimulation have been turned to account as scientists seek to understand the imitating body.

Tiffany Watt-Smith is British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow in the School of English and Drama and the Centre for the History of the Emotions, Queen Mary, University of London. This article first appeared in Wellcome History magazine.

Tiffany Watt-Smith is British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow in the School of English and Drama and the Centre for the History of the Emotions, Queen Mary, University of London. This article first appeared in Wellcome History magazine.

.jpg)

most interesting indeed