I’ve had quite a few conversations with colleagues about the challenges and rewards of archival research. We’ve talked about the joy of discovering a letter or memo or perhaps a collection of photographs barely touched for decades, as well as about the frustration of desperately trying to interpret unreadable handwriting that you just know holds information that could alter the entire course of your current research project. And of course, there’s no denying the kick you get from deciphering a private letter in Charles Darwin’s unintelligible scrawl, or the huge satisfaction that comes from finally tracking down a crucial piece of documentary evidence. What appears less likely to come up in conversation, however, are the sometimes emotionally fraught encounters with personal stories by and about people of the past. But what better place to contemplate one of the emotional challenges of doing history than a blog devoted to the history of the emotions?

I had my first encou nter with mouldy archival documents a few years ago as an MA student. I recall curiously studying the sombre faces of private patients who had been photographed for their records at the county asylum in Cheshire (pauper patients were not subjected to this particular form of visual documentation). Two years into my PhD research on melancholia in Victorian medicine I’ve grown used to the fact that archival research can at times be an emotionally challenging endeavour. This is perhaps particularly true when you’re writing about a disease concept that was according to nineteenth-century physicians characterised by ‘despair’, ‘guilt’, ‘depression of spirits’, ‘mental pain’, ‘fear’, and ‘suicidal propensities’.

nter with mouldy archival documents a few years ago as an MA student. I recall curiously studying the sombre faces of private patients who had been photographed for their records at the county asylum in Cheshire (pauper patients were not subjected to this particular form of visual documentation). Two years into my PhD research on melancholia in Victorian medicine I’ve grown used to the fact that archival research can at times be an emotionally challenging endeavour. This is perhaps particularly true when you’re writing about a disease concept that was according to nineteenth-century physicians characterised by ‘despair’, ‘guilt’, ‘depression of spirits’, ‘mental pain’, ‘fear’, and ‘suicidal propensities’.

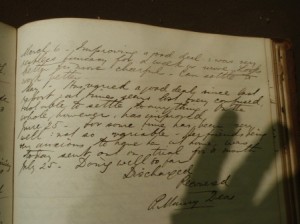

My most memorable case to date is not, however, one of melancholia. A while ago I was perusing the female casebooks from Brookwood asylum in Surrey. Upon turning a page I was met with an unusually brief case history (just over one page) of an unusually young patient (15 years old). What first caught my eye, however, was the article that had been cut out from a newspaper and glued onto the empty space next to the attending medical officer’s scribbles. Intrigued, I decided that this was a good time to take a short break from the research I was doing and began to read. It soon became evident why the notes pertaining to this patient were so brief – she lived only a short while after being admitted to the asylum a couple of weeks before the Christmas of 1870.

Fanny Evans, a young girl from Guilford in Surrey, was admitted following arrest for solicitation in London’s Hyde Park. The article that someone had cut out and pasted next to her brief case notes relates the story of a ‘lamentable case of profligacy’. According to the journalist, 15-year old Fanny has had a number of run-ins with the law, and when brought before the judge tells a web of lies in her defence, such as claiming that her father and brother are violent and abusive toward her. These ‘lies’ are perceived by the presiding judge of the Marlborough Police Court as further evidence of her morally corrupt character. The judge eventually concludes that ‘she has carried her profligacy to such extent as somewhat to have affected her mind’; thus, he recommends that she be sent to the county asylum for treatment.

Fanny arrives at Brookwood in an agitated state. She is described in her case notes as excited and delusional. The physician in charge states that she ‘appears thoroughly to believe’ her ‘delusions’, such as ‘that her father once tried to strangle her’. She is reported to have said that she would return to London as soon as she was discharged, ‘saying that her father is always threatening her and will not have her at his home.’

Shortly after she is admitted to the ward Fanny begins to have fits and suffers bouts of short-term memory loss. Two days later, on December 18, she is found dead in her bed following a seizure. The autopsy shows one side of the brain to be abnormally enlarged and containing a cyst. A large cyst is also found on one of her ovaries. An inquest is held into her death; the jury returns a verdict of ‘Death from suffocating during an epileptic attack.’

As an historian of the emotions and of psychiatry I am reluctant to assign any universalist, timeless qualities to feeling states, ‘experience’, or ‘illness’. It goes explicitly against the purpose of my work to retrospectively diagnose Fanny or try to interpret her emotional state, or that of any of the other Victorian asylum patients I come across. I know that I can never get to ‘what was really going on’ – all I have are the article and the medical case notes, both of which attest that Fanny Evans was ‘delusional’; therefore she was delusional, in this context, according to these sources.

Our present psychological categories are equally historically specific; in other words, it can be argued that the ‘empathy’ I feel for Fanny is just as culturally loaded as her delusions – but that makes it no less real. This story stuck with me to the extent that I used it when teaching an undergraduate seminar, and months later I’m now writing a blog post about it.

My own PhD research is explicitly premised upon the importance of recognising and explaining historical specificity. The categories available for expressing and describing one’s emotions form part of a knowledge system that determines the limits and possibilities of emotional experience. Historian and philosopher of science Ian Hacking has explained this much better than I ever could:

To create new ways of classifying people is also to change how we can think of ourselves, to change our sense of self-worth, even how we remember our own past. This in turn generates a looping effect, because people of the [new] kind behave differently and so are different. That is to say, the kind changes, and so there is a new causal knowledge to be gained and, perhaps, old causal knowledge to be jettisoned.[1]

However, the point of this is, in part, to say that it is through these kinds of processes that emotions and experience become real. And while one of the most important tools of any historian is critical thinking, I think our desire to critique is often driven by something much more emotive and much less talked about – empathy. While this emotion has its own history (as scholars such as Allan Young have begun to show), just like Fanny Evans’ ‘delusions’ it has through its history become a reified category of human experience. And while it may not be a timeless, universal emotion, it is at the same time precisely what allows the twenty-first century historian to reach back across time and interrogate the ideas and practices that produce a case like Fanny’s.

And as for Fanny herself – well, her ‘experience’ and ’emotions’ cannot be meaningfully recovered; however, empathy lets me imagine her pain as real, and that pain cannot help but fuel a need for historical critique.

[1] Ian Hacking, ‘The Looping Effects of Human Kinds’, in Dan Sperber, David Premack, and Ann James Premack, eds., Causal Cognition: A Multidisciplinary Debate, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1995, p. 369.

Pingback: New publications, April-June 2012 | The History of Emotions Blog