Paul Thomas Anderson’s latest film, The Master, tells the story of troubled drifter Joaquin Phoenix’s relationship with the head of a New Age sect, a sect which looks suspiciously like Scientology. The group, called The Cause, aims (like Scientology) to clear its members of the karmic traces of their past lives, and return them to their inherent perfection. They do this by hypnotising their members to retrace their past incarnations, or by subjecting them to a battery of psychometric tests with questions like ‘why do you loiter at bus stops?’

Like Scientology, the Cause records all these confessions through microphones, to create a huge database of personal indiscretions. I find the technology of spirituality fascinating – all the gadgetry that humans have invented over the millennia to help us escape the material prison, from shamanic regalia, to the confession box and rosary, to the orgone box and the dianetics machine of modern ‘scientific’ religion. We yearn to escape materiality and come closer to God, yet when we look behind the veil of religions, we often discover cheap stunts, pseudo-science and tawdry showmanship.

The head of the Cause, played by Philip Seymour Hoffman, is part-Svengali, part-PT Barnum. One is never sure how much he believes his own hype. For almost all of the film, he is a flouncy performer, playing up to his adoring devotees. Only once do you see him alone, off-stage, looking out through the slats of a blind at the empty stage and the crowd awaiting him. Briefly, you see the lonely soul trapped within the public persona, the diminutive figure behind the Wizard of Oz, the child longing to stop the pretense. He declares, when he first meets Phoenix, “I am a writer, a doctor, a nuclear physicist, a theoretical philosopher…but above all I am a man” – you wonder if he wishes he was just the latter.

Phoenix, meanwhile, is unbearably compelling to watch. His very skin and veins seem to pulsate with tormented animal spirits, like a painting by Bacon. He is Caliban to Hoffman’s Prospero, longing to govern his demonic compulsions, while Hoffman’s faux-guru is drawn to him precisely for his wildness, his spontaneity, his authenticity and the promise he carries of escape from responsibility.

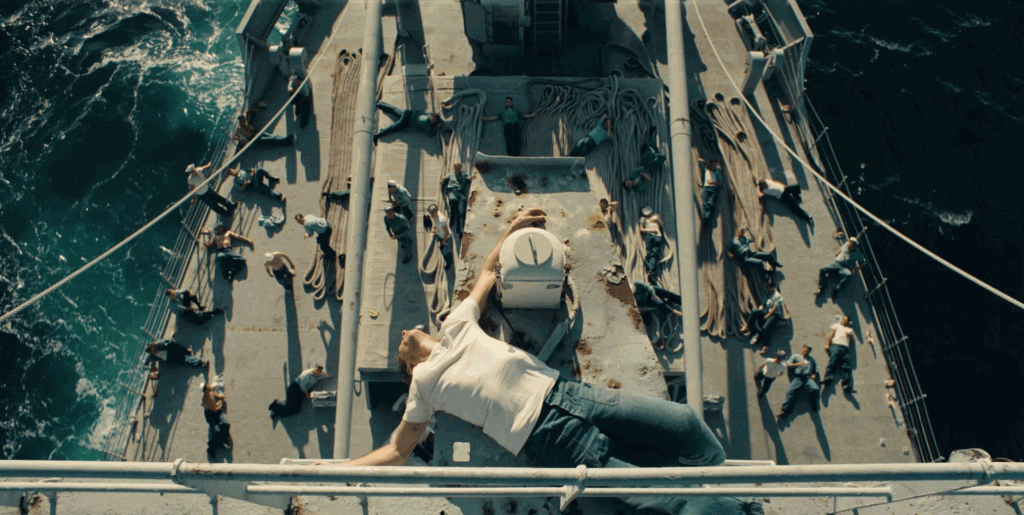

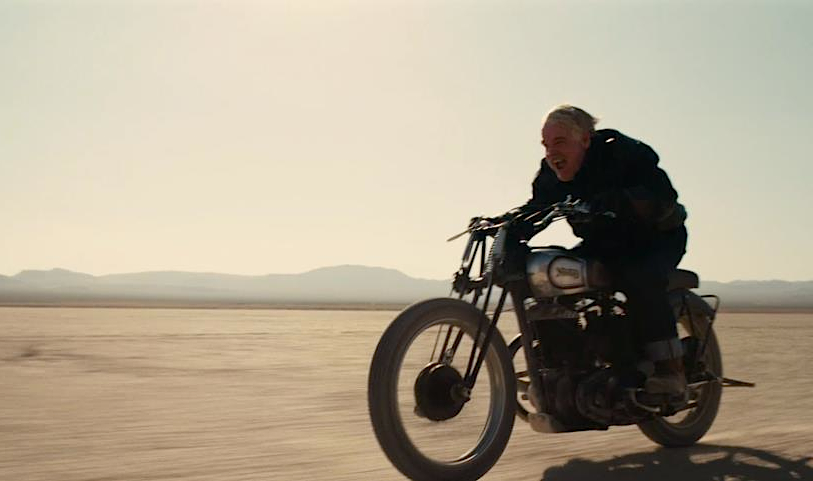

The film, like the Great Gatsby, is an exploration on how the Puritan desire to escape the sinful past takes some very weird forms in modern American culture. You realise both the main protagonists are trapped in their past, in their roles, both dreaming of escape, both destined to fail. The past stretches out behind us, like the wake of a ship (in one of the film’s recurring images). We can try to outpace it, like Phoenix riding a motorbike at breakneck-speed across the desert and into the horizon. But when we arrive, our past is already there, with all its claims upon us. It reminds me of the old Looney Tunes cartoon, where an escaped convict is being hunted by Droopy, the lethargic basset-hound. No matter how far and fast the convict runs away, somehow Droopy is always there, waiting for him.

This is cinema that proves a close-up of an actor utterly inhabiting their character can be more breath-taking than any 3D spectacular. Anderson continues to explore the rocky terrain of modern loneliness and our yearning for community, forgiveness and transcendence. In contemporary American cinema, he is the Master.