Last month, author David Kerekes spoke at one of our QM history of emotions lunchtime seminars about his new short novel: Mezzogiorno. In this blog post David writes about some of the background on how Mezzogiorno came to be.

Last month, author David Kerekes spoke at one of our QM history of emotions lunchtime seminars about his new short novel: Mezzogiorno. In this blog post David writes about some of the background on how Mezzogiorno came to be.

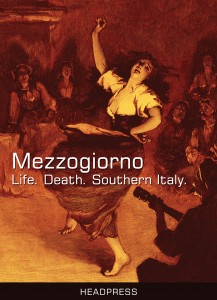

A free extract from Mezzogiorno: Life. Death. Southern Italy. by David Kerekes (pub Headpress 2012) can be found here.

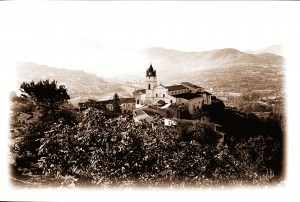

I had not stepped foot in the mountain village of Montefalcione for more than twenty years when the imminent death of my mother precipitated my return in 2006. The village is in southern Italy, located in the province of Avellino in Campania, some 523 metres above sea level. In the last week of August, Montefalcione is host to a festa (party) devoted to its patron saint, Sant’Antonio di Padova, during which the unassuming streets are decked out with lights and musicians and inundated with visitors, no less a Diaspora returning to the place of their birth (among their number my mother).

I was quite prepared for the bitter fruit of such mitigating circumstances, of returning to the village after twenty years at the behest of a dying parent, but what I found in 2006 was something wholly unexpected.

Southern Italy is depicted in the history books as a cruel and amoral land overrun with brigands and devils. The territories of the south begin with Rome, perhaps Naples, and they stretch down to the islands of Sicily and Sardinia, becoming collectively the Mezzogiorno, which means midday sun, or, that blistering and rotten country. The geography of the south is harsher than that of the north, its economy poorer, and its culture occult and mysterious.

Nothing much had changed since I last visited Montefalcione. The pace of life had not picked up so that I could notice: Old people still observed the street from their chair at the door; Tony’s bar remained a fixture in the playing of Scopa and Briscola, the traditional card games; and men of the comune, the local council, still had a lot of things to shout about. The place quickly assumed the disquieting dream like quality I held for it in my thoughts, in no small part attributable to the folkloric stories of my mother and her childhood, in which family and Church are sacrosanct. In these stories the living often walk with the dead, and almost no division exists between real and unreal.

The soundtrack for the festa is the hymn of S. Antonio. This sober musical phrase plays on a loop from a speaker and serenades the statue of the saint as it travels through the village on the back of a truck. It ebbs and flows on the mountain and can be heard for miles, rallying funds for the procession of S. Antonio that takes place on the Sunday, when the statue will be carried through the streets (bedecked in a coat fashioned from the silver and gold trinkets and jewellery donated over the years). Fireworks are another key aspect of the festa. The breathtaking display of pyrotechnics that conclude the festa on Monday is anticipated each morning by thunderous practice charges, which rattle the wind and S. Antonio’s melancholic theme.

From what I could determine, the influx of tourists in 2006 was greater than the preceding years (and has increased exponentially since). The architects of these old streets, said one member of the comune, could never have expected it. Indeed not. They had more in mind peasants, the occasional latifondista, chickens and goats. With dusk, people begin to saunter down Via Pieschi and Via Roma, where gaudy bancarella have been erected selling tat, arriving at the piazza where the entertainments begin. This part of the village retains much of its antiquated flavour, and the entertainment in 2006 comments something of the fact with a medieval theme, including revellers in armour, a re-enactment of a scene from Romeo and Juliet, and lots of food and wine. On one small street are the antichi mestieri, examples of traditional work craft as demonstrated by old folk. The street is nameless but comes out beneath an archway that carries a fitting crest: Porte del Tempo (Gates of Time). A TV crew has arrived and interviews one barrel maker behind a cigarette, documenting for posterity a former generation and its trade.

And of course there is the music.

There is no shortage of musicians during the festa, and in the old part of town they are found. Small bands, or gruppi itineranti (travelling groups), comprising mandolin, squeezebox and sometimes tambourine or castanets, play a traditional music known as tarantella, which is a swift, loose and hypnotic type of music without any discernable beginning or end. The tarantella dates back to the Middle Ages, perhaps earlier. One legend claims an infestation of tarantula spiders in Taranto, a city in Apulia on the coast of southern Italy, gave rise to it. When bitten by a tarantula, the inhabitants of Taranto would flail and dance to frenetic rhythms to try and rid themselves of its poison. An expansion of this legend suggests the venom had hallucinogenic qualities, hence the vigorous dancing. Others regard stories about invading tarantulas as fudge for the constraints placed upon dancing by the church at that time.

There are three churches in the village of Montefalcione. Of these, S. Maria Assunta is the chiesa madre, the mother church, situated at the highest tip of the mountain. This is where bidding will take place for those men who wish to be the statue bearers for S. Antonio, a great and expensive privilege. The statue on its tour will be accompanied by a brass band wearing black shirts and grey neckties, colours representing death and mourning, or in the Christian faith the mortality of the body and the immortality of the spirit. Next to the church of S. Maria Assunta is a vantage point that overlooks the village and where, for the festa, a stage has been erected for groups to perform.

The head of the dance leads his troupe up Via S. Angelino da Padova. We pass a circle of people observing other musicians playing an equally engaging music, and a young couple dancing in a slow, precise and yet almost disengaged manner. It’s an inversion of the usually frenetic dance associated with the tarantella. (I would see an old-timer dance this exact same way during another festa, in Galatina in Apulia, which is the spiritual home of the tarantati, those people exhibiting symptoms of the tarantula bite.) The steep cobblestoned climb finds us at the brooding doors of S. Maria Assunta. To the left of these doors, in the corner of the village, is the vantage point whose glorious view spans the whole of the mountainside, and where, on the specially erected platform, another group of musicians are already playing.

At the fore of the stage, clutching a glass of wine, soon replaced by the bottle, a grizzled fellow in a t-shirt and an aged tattoo down one arm makes a rasping introduction. He looks not unlike a sailor on shore leave.

The crowd stands and watches as a beat provided by the tamburelli augments with an accordionist who carefully picks out a melody.

The group is called Zimbaria, named after the man at the front with the wine, Pino Zimba. Zimbaria hail from Salento, southern Apulia, the so-called ‘heel’ of Italy, and their repertoire is almost exclusively traditional songs. Pino Zimba’s introductions to these songs, like the lyrics themselves, are set in the dense colloquial brogue of his homeland, close to impenetrable to the Montefalcionesi audience. Zimba notwithstanding, the group are a relatively young bunch, among them a gifted accordionist, two guitarists, a violinist and a large lute. A vocal contingency within the audience is young, too, having made the trip especially to see Zimbaria play. This is evidence of a resurgent interest in traditional music in the Italian south. Zimbaria are a far cry from some other groups playing the festa and the type of groups I recall from my own childhood, playing at functions organised for the Italian Diasporas across the UK, notably Bury and Bedford. Music in this instance was attuned to family entertainment, performed by uniformly dressed musicians on harsh electrical instruments. It served its purpose but was very uncool.

Pino Zimba was to die of cancer soon after the performance in Montefalcione. This cemented his status as Italian folk hero, with tribute concerts taking place (and continuing to take place) throughout the south. I would attend some of these concerts in what was to become an infatuation with the music of the tarantella. I spent some months travelling to places that were key in its legend and, moreover, the legend of tarantism itself, where the roots of the tarantella lie. My departure point was of course Montefalcione, in a search for the forces evoked that night of the Zimbaria gig. Therein lay enlightenment and purpose, and its road — a secret road manifest only in the steps taken upon it — I found and followed, returning some years later with a novel I called Mezzogiorno.

[The above text is an extract from Gathering of the Tribe: Music and Heavy Conscious Creation, Mark Goodall, pub Headpress 2012]

© David Kerekes 2012