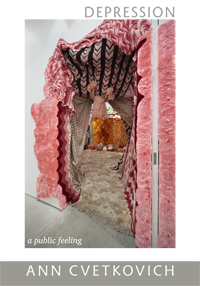

Ann Cvetkovich, Depression: a Public Feeling. (Duke University Press, Durham & London, 2012).

Reviewed by Sarah Crook.

Ann Cvetkovich’s Depression: a Public Feeling forms a part of a broader project under way in the United States around the rubric of ‘Public Feelings’. The Public Feelings project, which developed in the early 2000s, has sought to navigate and understand the emotional dynamics of contemporary life within the political and power structures from which they emerge. Public Feelings configures emotions as both a subject of analysis and as a methodological tool. Within this intellectual context, Cvetkovich seeks to explore ways of writing about depression that move away from medical conceptualisations towards a model of depression as a cultural and political phenomenon – a mode of disillusionment and discontent that reflects, and is produced by, the shape and textures of contemporary society and late capitalism. Rather than a disease that plagues the individual, this positions depression as a political and social feeling.

Depression: a Public Feeling takes the form of a combination of memoir and critical essay. Cvetkovich articulates the problems wrought by combining these two forms of writing, and in particular the shift required for an academic to contribute to the memoir genre (Cvetkovich is Ellen C. Garwood Centennial Professor of English and Professor of Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of Texas, Austin.) She reflects that she committed to the memoir as a way of ‘figuring out what memoir can do for public discourse’, rather than participating in its deconstruction and critique. The decision was wise: the memoir section of the text is rich in its sensibilities, and is ultimately uplifting without being trite. In particular, her account of her depression offers the neat example of how small acts of self-care, such as visiting the dentist, can counteract the condition’s paralyzing effects. Such acts of self-preservation allowed Cvetkovich to take some ownership – even whilst surrendering control – of her life and wellbeing. Unlike other contributions to the field, her memoir is not (primarily) an account of the effects of pharmacological treatment. Although Cvetkovich does write about her experiences of taking medication (and attempting therapy, although she concludes that ‘the dentist was ultimately of more use to me than the therapists’), she is more interested in how forces outside the cultural and medical mainstream can destabilize our understanding of the condition.

How depression as a public feeling might be shaped and challenged by cultural forces is the subject of the second half the text. Here, Cvetkovich draws on queer theory, and explores how histories of oppression have shaped the experience of emotional distress. There was, perhaps, a missed opportunity here to discuss how the recent economic depression has impacted the articulation of emotional depression, and how economic structures exacerbate affective experiences. However, the section on the legacies of colonialism, genocide and oppression is fruitful. Cvetkovich claims in the introduction that ‘Depression, or alternative accounts of what gets called depression, is thus a way to describe neoliberalism or globalization, or the current state of political economy, in affective terms’, and the chapter on racism goes some way towards offering a vision of how this might be carried out. This chapter sees Cvetkovich draw on a critical reading and reinterpretation of a number of books that explore the legacies of racial discrimination. However, a fuller analysis of how racial and structural inequalities impact on the emotional lives of the white population would have been welcome here, given Cvetkovich’s own racial and socio-economic profile and the privileges made apparent in the text’s memoir section.

In the final section of the text this problem of privilege is made clear. Cvetkovich finds respite from her depression in spiritual practice, ‘a version of the utopia of ordinary habits’, which transforms rituals into forms of embodiment or through creative enterprise. This, she acknowledges, may be problematic for those sceptical of spiritual or quasi-religious language, and indeed I remained unconvinced. Her detailed excursion into the emotional and cultural potentialities of crafting, whilst allowing the text itself to be enhanced with some fascinating and lovely images of installation art, fell a little short of proposing the radical alternative model of cultural engagement with depression that the text seemed to demand. Despite this, however, the text successfully formulates a new way of writing about depression and should prompt some introspection from those within academia about the value of combining critical literature with personal accounts of emotional experiences. Certainly there should be alternatives to the medical model of depression: Cvetkovich’s contribution is to be warmly welcomed and discussed.

Sarah Crook is a PhD candidate at Queen Mary, University of London within the Centre for the History of the Emotions. Her research, funded by the Wellcome Trust, explores maternal distress from the mid to late twentieth century in Britain. She is co-convener of the History of Feminism Network and tweets at @SarahRoseCrook.

This is fascinating as I often think of my own depression as being less of a personal think, more of a reflection of the society I grew up in. Since moving to a country where there is more emphasis on the group rather than individual (too much I would say) I have noticed it abate a little (tho meditation, literature and exercise have as much to do with that as anything). I have come to see how important it is to have a place and a sense of belonging. As I say it can be too much at times; people can become incapable of being alone or achieving things without others, which can also be destructive. I am a firm believer that our science reflects our society and that while of course mental health problems are very real and medication does really help some, for many of us being labelled makes us more self aware (a trait almost all depressed and anxious people I have met share) and makes us analyse each and every action to see if it reflects the medical definition of our “disease”. The very medical profession that purports to help us only worsens the situation as it falls back on an overly intellectual response to a problem that necessitates something more emotional, something less black and white. The craft projects that the writer speaks of may seem trite but it is a chance for those of us, or at least some of us, whose, supposedly rational, minds are against them to do something less thought based, more tangible. It slows us as prayer slowed down the mind of generations before us. If advances are to be made in the treatment of depression it must be adaptable to the individual. Medicine must accept that it is not a true, objective science but one that must provide blueprints that can be altered for each individual .

I think you’ll find most minorities depressed at some point or other. 28th Aug – the 50th anniversary of MLK speech ‘I had a dream’…. For some dreams will just be dreams and nothing more. Mainstream society needs to wake up to the fact that it won’t be liberated until its minorities have equality. It’s the measure of a healthy society.