Dr Helen Rogers is Reader in Nineteenth-Century Studies at Liverpool John Moores University, and the author of the blog Conviction: Stories From a Nineteenth-Century Prison. She is also one of the editors of the Journal of Victorian Culture. In this post for the History of Emotions blog she writes about her research into juvenile criminals, including their friendships and tattoos, subjects she also speaks about in Episode 6 of ‘Five Hundred Years of Friendship’.

Dr Helen Rogers is Reader in Nineteenth-Century Studies at Liverpool John Moores University, and the author of the blog Conviction: Stories From a Nineteenth-Century Prison. She is also one of the editors of the Journal of Victorian Culture. In this post for the History of Emotions blog she writes about her research into juvenile criminals, including their friendships and tattoos, subjects she also speaks about in Episode 6 of ‘Five Hundred Years of Friendship’.

__________

We’ll never know who coined the phrase ‘as thick as thieves’ to describe close and furtive acquaintances but the phrase had currency by the late 1830s when it began to appear in fiction and newspapers.[i] The timing is striking for it coincides with growing cultural anxieties about the rise of a ‘criminal class’ inhabiting a clandestine world of ‘hardened’ offenders bound by ‘evil associations’ and ‘bad connections’.

Poor and unprotected children were deemed particularly susceptible to ‘contaminating influences’.[ii] Nowhere was this evoked more vividly than in Oliver Twist (1837-9) with its fascinated horror in the tight bands of boisterous, street-wise youths and their corruption by professional thieves. In Dickens’s portrayal of the wily Fagin and his artful dodgers, the novel speaks to enduring concerns about unregulated childhood friendships and inappropriate adult-child relationships that underlie our preoccupation with ‘grooming’.

What can these cultural anxieties tell us about the experience of youthful companionship in the past? Here I trace the friendship networks of boys and youths who served time at Great Yarmouth Borough Gaol in the 1830s and 1840s. Law enforcers in Yarmouth frequently observed the link between offending and ‘bad connections’, namely relatives and friends. In his report when dispatching sixteen-year-old Thomas Bowles to the hulks, the Gaoler noted: ‘Bad character and connexions. Hasty disposition.’ Sentencing Thomas to seven years transportation for theft, the magistrates hoped he would be sent to one of the new ‘reformatories’ designed to rehabilitate young offenders.[iii]

In 1839-41, 41% of prisoners at Yarmouth were aged eighteen or under, mostly convicted of vagrancy, petty theft, and absconding from apprenticeships.[iv] While the authorities did little to address the causes of youth offending, Sarah Martin, a local dressmaker, voluntarily ran a pioneering scheme of prisoner rehabilitation. She spoke to inmates as a friend and fellow sinner, like other Christian philanthropists committed to ‘loving the sinner, not the sin’. Less common, the Christian fellowship she offered prisoners extended to teaching reading and writing, training in useful work, and helping discharged prisoners find employment. Knowing the likelihood of their reoffending, she worked assiduously with first-time offenders. Her notes on inmates before and after their release indicate what they had to gain by her assistance and the challenges they faced in following her strict programme of Christian improvement, as we can see by following Thomas Bowles through his early convictions to his transportation.[v]

‘Sarah Martin and her Jail Congregation’, Women of Worth: A Book for Girls, illustrated by W. Dickes, (London: James Hogg, 1859)

Swiftly following a short remand, Thomas was imprisoned again, aged 14, for three months in 1841 for breaking into a shop and stealing with Joshua Artis (16) and Edward Juniper (13). Martin thought Thomas a ‘clever boy – and both diligent and obedient’. While regretting he had a ‘bad father’ and that his mother was ‘in want and distress’, she hoped with ‘judicious guidance he might become a better character’.[vi]

Like other Christian reformers, Sarah Martin believed lack of moral and religious training was the cause of much delinquency. She taught young prisoners by using picture-story books which stressed the need to be good and kind friends to each other and dutiful to their parents and teachers, while illustrating the dire fate awaiting wicked and idle children. The prison scholars enjoyed these books, despite their humourless didacticism, asking for more each day.[vii] Learning and useful work were valued distractions from the tedium of confinement, as the ‘diligent’ Thomas must have found. Many acquired literacy remarkably quickly, often by helping each other with their letters. Few were prepared to forgo the opportunity of instruction and consequently inmates policed themselves in class and rarely were punished for misconduct. If their prison schooling was effective, it was in part due to companionship between cellmates.

The Gaoler’s disciplinary record exposes, however, the different tenor of inmate relationships when left to their own devices. Thomas, Joshua and Edward were punished several times during their sentence for fighting, quarrelling, and making noise together. Their unruly behaviour continued on release for within months they were back in prison for stealing a bottle of wine.[viii] In the 1840s, prisons were increasingly turning to solitary confinement to prevent inmates ‘contaminating’ each other, especially the young, but at Yarmouth most spent the day in small wards where friendships were forged and rivalries battled out. Juveniles were by far the most troublesome inmates, particularly boys under 17. While some met ‘partners in crime’ in gaol, many knew each other from outside. Overwhelmingly, friendships were between boys of a similar age rather than with the career criminals feared by social commentators.

In their raucous behaviour, the boys asserted their place in the inmate pecking order, stood up defiantly to authority, and sought to control the prison environment with their loud and disruptive use of space. In nine imprisonments before he was transported, Joshua Artis was punished eighteen times for talking with prisoners in the chapel, insolence to the gaoler and chaplain, and for being always ‘Idle and Artful’. Acting out his cockiness for his own and others’ amusement, Joshua climbed the prison walls with one cellmate, threw water over another, shouted to get the attention of the female inmates, and so on.[ix]

Both the boys’ offending and their bravado seem to have been responses to their precarious position in the family home and the labour force as well as their imprisonment. Most had finished what little schooling their family could afford and were expected to pay their way. Though few had no family ties, two-thirds of those transported had lost a parent, which suggests the immediate support networks of many juveniles were similarly compromised by bereavement and poverty. Thomas Bowles’s family, for instance, had been deserted by his father and he had spent time in the workhouse where he had been a ‘refractory pauper’.[x]

Work, play and offending merged with each other. Boys were prosecuted, frequently together, for swimming where it was prohibited, removing sand from the shore, stealing rope off the docks, and letting boats adrift. Some were fortunate to have an apprenticeship yet struggled to adapt to work discipline, often losing their employment through absence. Most depended on casual labouring jobs or occasional sea voyages, as did Thomas, but supplemented irregular work by pilfering. Provided her young scholars appeared committed to reform when released, Sarah Martin would help tide them over until they found a job, giving them a basket and a weight of fish so they could support themselves by hawking. She also kept a close eye on them.

The prison visitor recommended Thomas to a Sunday school and ordered him a two-penny loaf for the Sabbath and a blue slop at the end of the month if he attended. The boy called to say he had found work as a bricklayer’s labourer and could pay his sister for sheltering him. He was anxious to assure the teacher of his good conduct. He had met a prison friend, he explained, who ‘asked me to go with him in a boat on Sunday but I told him I would not, for I should go to the school, and said “You had better go to:” he said “Well, perhaps I shall.”’ But when next the teacher called on Thomas, she found him without work and playing marbles. This prompted a lecture. If he wished to play, he should drive a hoop or throw a ball; marbles was a form of gaming that would lead to worse. She was relieved when he won a berth on a fishing vessel for which she bought him canvas trousers.[xi] But her support seemed to come to nothing for the boy was imprisoned for leaving his master before being sentenced to transportation for housebreaking.[xii]

With their precarious networks of support, laddish behaviour gave boys like Thomas much needed companionship and relief from the hard task of survival. Without the steadying influences of regular employment and their own family and dependents care for, male juveniles were by far the most likely of Martin’s ‘liberated prisoners’ to reoffend. Two-thirds of repeat offenders at Yarmouth were under twenty-one. They also featured heavily in the persistent offenders who were transported.

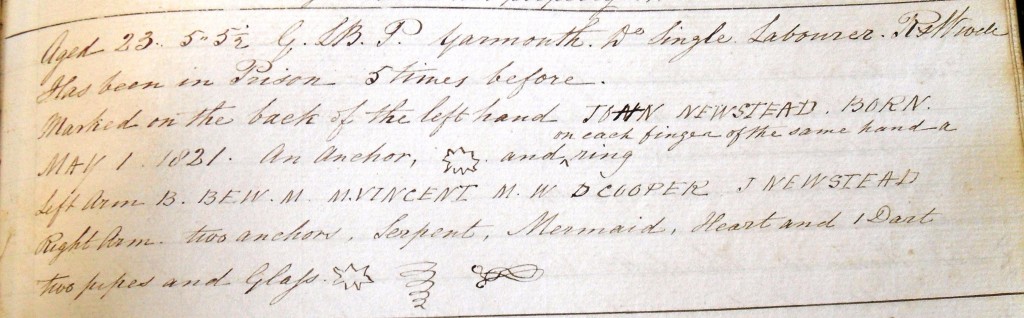

The convict records of these boys and young men reveal the allegiances and habits which militated against the pious intervention of the prison visitor.[xiii] Among their physical characteristics listed on their convict records can be found the descriptions of their tattoos. All most all had elaborate tattoos marking the names of family, loved ones and friends which reveal the strength of their attachments. One had the names of the boys with whom he had been convicted and others he met in gaol.[xiv] Another had an image of two men arm-in-arm, probably the brother with whom he was transported.[xv] Many wore blue dots, perhaps denoting gang membership.

Their tattoos, often begun in their early teens, also signalled the boys’ efforts to join the adult world of Yarmouth men, based around heavy labouring occupations, sea-faring, and the tavern. Joshua Artis displayed his hardy defiance of authority: ‘Man with staff in one hand cuffs in the other.’[xvi] In a port where lives depended on the sea and fate loomed large, their tattoos bore the superstitious, gambling and risk-taking elements of this culture. Most, including Thomas, wore the maritime symbols of mermaids and anchors, with their promise of safe passage. The tattooed ‘fouls’ on Thomas’s arms no doubt showed his love of cock-fighting and the failure of his teacher in warning him against gambling.

Among the most repeated images in the convicts’ tattoos were pictures of men smoking and drinking, crossed pipes and cupped glasses, the symbols of masculine camaraderie and conviviality. In their tattoos, then, these boys and young men celebrated the friendships that sustained them and on which, they had imagined, they would build their future.

Illustration 2: John Newstead’s tattoos, described by Gaoler, 8 June 1844, showing the names of friends and crossed pipes and glasses.

__________

Follow Helen Rogers on Twitter: @helenrogers19c

Read more at the Conviction blog

Return to: Five Hundred Years of Friendship at the History of Emotions Blog

[i] The earliest reference I can find via Google Books is in the novel Mayne Reid, Osceola the Seminole (1818), though there are no more until T. Hook’s The Parson’s Daughter (1835). The earliest newspaper reference via the British Newspaper Archive is in relation to the Tories in an election covered by the Western Times, Devon, 19 August 1837. Thanks to Miriam Cady and Robin J. Barrow for searching Eighteenth Century Collections Online for me.

[ii] Heather Shore, Artful Dodgers: Youth and Crime in Early Nineteenth-Century (London, Boydell Press, 2002)

[iii] Thomas Bowles, per Asiatic, 1843, Police no. 10001; database no. 6264; Conduct Record, CON33/1/42; Convict Indent, CON14/1/24, State Archives of Tasmania. Bury and Norwich Post, 4 Jan 1843 p. 3

[iv] Based on analysis of Gaol Registers.

[v] Anon. Sarah Martin, the Prison Visitor of Great Yarmouth, with extracts from her Writings and Prison Journals, a New Edition with Additions. London: Religious Tract Society, n.d. [1847]. Helen Rogers, Kindness and Reciprocity: Liberated Prisoners and Christian Charity in Early Nineteenth-Century England, Journal of Social History, Spring 2014, 47.3: 721-45.

[vi] Gaol Register, 15 December 1841; Martin’s Register 1841, no. 106. All the gaol records are held at Norfolk Record Office. Sarah Martin’s surviving journals are on display at the Tolhouse Museum, Great Yarmouth Museum Services.

[vii] Helen Rogers, ‘“Oh, what beautiful books!” Captivated Reading in an Early Victorian Prison’, Victorian Studies, Vol. 55, No. 1 (Autumn 2012), pp. 57-84.

[viii] Gaol Keeper’s Journal, 1841-5; Gaol Register, 20 June 1842.

[ix] Gaol Keeper’s Journal, 1836-40 and 1841-45.

[x] Sarah Martin, pp. 130-2.

[xi] Sarah Martin, pp. 130-2.

[xii] Thomas Bowles, per Asiatic, 1843, Police no. 10001; database no. 6264; Conduct Record, CON33/1/42; Convict Indent, CON14/1/24.

[xiii] Between 1836 and 1852, twenty-six boys and young men were transported to Van Diemen’s Land who had begun offending at Yarmouth when under twenty one. (A similar number were transported elsewhere). All but 3 were tattooed according to their convict records.

[xiv] John Newstead, 21025, per Ratcliffe (2), 1848, CON33/1/91, CON14/1/40 (see image)

[xv] Isaac Riches, 17982 per Joseph Somes (1), 1846, CON33/1/77, CON14/1/35

[xvi] Joshua Artis, 15826, per Theresa, 1845, CON33/1/67, CON14/1/29.