My great-great-great grandfather, a York Quaker called Henry Isaac Rowntree (that’s him on the left), set up Rowntree’s chocolate company in York in 1862. He was an amiable young man, ‘perhaps the only Rowntree with a sense of humour’ according to one historian. He had a parrot who liked to shout obscenities from under the table, much to the consternation of the Quaker elders when they visited. Henry loved adult education and journalism, but family members feared he knew ‘next to nothing about business’.

My great-great-great grandfather, a York Quaker called Henry Isaac Rowntree (that’s him on the left), set up Rowntree’s chocolate company in York in 1862. He was an amiable young man, ‘perhaps the only Rowntree with a sense of humour’ according to one historian. He had a parrot who liked to shout obscenities from under the table, much to the consternation of the Quaker elders when they visited. Henry loved adult education and journalism, but family members feared he knew ‘next to nothing about business’.

This led to him not being invited to be a partner at the family grocery business in York, so instead he bought a cocoa company set up by a plucky Quaker called Mary Tuke. A few years later, the company was in financial difficulties. Bankruptcy was the height of shame in the Quakers – indeed, you were ejected from the church for it – so Henry’s older brother, Joseph, came to help him run it. Joseph was much more sensible and meticulous, and public demand for cocoa powder and chocolate was beginning to take off.

By the 1940s, Rowntree’s had become one of the biggest confectioners in the world, making well-known brands like Aero, Rolos, Kit-Kat, Polo, Black Magic, and Rowntree’s Fruit Pastilles. Alas it was sold to Nestle in 1988, and Joseph had already given away all the money he made to his charitable trusts, so distant descendants inherited not so much as a packet of Smarties.

Nonetheless, Rowntree’s are still relevant to my interests because the company was a pioneer in adult education, and well-being-at-work. In fact, when I went to a conference on well-being-at-work, organised by Robertson Cooper last year, the first speaker began his keynote with a slide of the Rowntree’s factory.

So what can the example of Rowntree’s tell us about well-being-at-work?

1) Rowntree’s made worker well-being a priority

Rowntree’s, like its Quaker rival Cadbury’s, was run in a spirit of industrial paternalism. The workers were treated not as mere cogs in a machine, but as characters to be developed (and souls to be saved). Rowntree’s was one of the first companies to have dedicated ‘welfare officers’ – what today we’d call human resources managers – whose job was to look after the well-being, education and moral character of the young (14 and up) male and female workers.

There was also a medical officer, regular medical and dental examinations, and company public health campaigns against the evils of tobacco and booze. The dentist, I am informed by wonderful Rowntree archivist Alex Hutchinson, was an alcoholic fascist who often removed far too many teeth…well, you win some, you lose some.

As the company grew to a staff of 4,000 or so, Joseph Rowntree was keen to make sure it was still ‘united by a common purpose’. To that end he introduced one of the first in-house company magazines, as well as group-bonding concerts, theatricals, feasts and field trips. One trip involved sending the workers on a walk across the Yorkshire dales. Unfortunately it rained, the workers repaired to a nearby pub, and after an afternoon’s intensive drinking, the police had to be called to eject them.

Historical accounts, like this history of Rowntree female employees, suggest workers enjoyed working at the firm

The Rowntree’s also supported workers’ education through libraries, discussion groups, the Yorkshire philosophical society, and through a network of adult schools. Quakers played the leading role in the establishment of adult education at the end of the 19th century – by 1900 there were 350 adult schools around the UK, with 45,000 pupils, of which two-thirds were at schools run by Quakers. Many Rowntree family members were actively involved in setting up and teaching in adult schools – the school they all taught at was round the back of their grocery business on the Pavement in York.

Some of the Rowntree staff lived in a ‘model village’ launched by Joseph Rowntree, called New Earswick. It was inspired by the ‘garden city’ designs of Ebenezer Howard, with worker cottages, a village green, and a veritable Quaker porridge of village committees – a library committee, a women’s guild, an orchestral society, a village council, a men’s social club, a musical society etc etc etc. It’s still going.

Historical records suggest that, to a large extent, Rowntree employees enjoyed working there, forged good relationships, and were happy – indeed, Rowntree women were famous for singing at work, as this short film from 1932 shows.

2) This sort of Quaker industrial paternalism was potentially patronising and illiberal

However, the strong emphasis on worker welfare could potentially be creepy – the company poking its nose in your inner life. Fry’s Chocolates, for example (another Quaker company), held an annual workers prayer service, which Joseph Fry said was ‘often a means of observing their conduct and checking any tendency to impropriety’. The Rowntree’s welfare officers, known as ‘overseers’, were also sometimes resented (‘she sits up there like the Queen of Sheba’, one worker complained).

Workers might well feel that what they did in their own time was their own business, and that the imposition of Quaker ethics on them was an infringement of their own religious liberties. So what if they drank in their own time? Should that be a cause for sacking, as it was at Fry’s? When did religious non-conformism become so conformist?

The Quaker emphasis on character and do-gooding could be annoying and patronising, as one poem showed:

Take a dozen Quakers, be sure they’re sweet and pink

Add one discussion programme, to make the people think

…Garnish with compassion – just a touch will do

Serve with deep humility your philanthropic stew

A modern equivalent of Rowntree’s focus on worker-welfare might be something like the American shoe company Zappo’s, which also is something of a personality cult of its CEO, Tony Hsieh, and also has a strong emphasis on employee well-being. Reading Hsieh’s smug and self-congratulatory comic book, Delivering Happiness, makes me feel queasy – Zappo’s sounds like a bit of a happiness police state.

It’s important, then, for companies to think about how to balance a strong collective ethos with autonomy, how to create a culture that encourages people to be individuals rather than clones, how to create room for dissent and satire, and how to make sure their well-being programme doesn’t feel forced, patronising, conformist. or a form of illiberal surveillance.

Saracens rugby club is an interesting example here – its ethos was also inspired by a strong Christian emphasis on the well-being and personal development of its staff and players, but manages to find a way to promote this without being too patronising, and with room for dissent. Staff and players are co-creators of the culture, rather than merely automatons to be programmed.

3) Ethical capitalism always has its internal tensions

The Quakers helped to set up some of the best British companies – Rowntree’s, Cadbury’s, Barclays, Lloyds, Clarks, Friends Provident – most of which strived to be not just profitable but ethical. They were family-owned, meaning they could pursue their own values rather than trying to please distant shareholders. They were often run as quasi-mutuals, ‘as a kind of partnership between masters and men, uniting their labour for a common end’, as Joseph Rowntree put it. Rowntree’s had a ‘Cocoa Council’, which elected MPs from every department.

In all of this, perhaps there are lessons for our own time, when corporations have come to be seen as psychopathic, and when Barclays and Lloyds have become by-words for dodgy dealing (indeed, Barclays’ CEO, Anthony Jenkins, recently suggested the firm needed to remember its Quaker history).

However, Quaker capitalism always had its internal contradictions and tensions.

Quakers blossomed in business partly because their religious non-conformism meant that historically they were unable to go into other careers like politics, partly because they had amazing networks of trust between themselves, and partly because their austere Puritanism made them very good at meticulous book-keeping and rational management. But, as Max Weber explored in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, there was a paradox in directing this Puritan zeal towards the accumulation of capital.

Quaker businessmen had a constant struggle to try and balance their service both to God and to mammon. For example, Rowntree’s initially rejected advertising as insincere and duplicitous, but quickly realised they had to embrace it to compete. Both Rowntree’s and Cadbury’s used their ethical principles as a form of advertising, which works from a marketing point of view but is not really in accord with the Gospels. They also spied on each other to try and get each other’s recipes – this was the inspiration for Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. They colluded and set prices when it suited them. Both families made their fortunes by profiting on our growing addiction to sugar – which was originally intended to wean the nation off alcohol but has become its own public health menace.

And the family-ownership model depended on having family members with the genius for business. The Rowntree heirs became increasingly interested in different things, so the company appointed its first non-Rowntree chairman in the 1930s – George Harris, my great-grandfather, who married into the family.

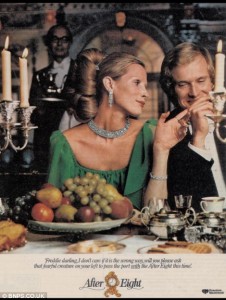

Harris wasn’t a Quaker and had little time for their Puritan do-goodiness. He was more inspired by the American Forrest Mars, who once told his employees: ‘I am a religious man…I pray for Milky Way, I pray for Snickers…Profit is our sole objective.’ Harris used marketing research to launch the very un-Quaker ‘Black Magic’, advertised as a tool for seduction! Rowntree’s, which initially spurned advertizing, became a master of it. Indeed, the first ever ‘talkie’ advert was a seven-minute Rowntree’s ad for ‘Plain Mr York’. By the 1980s, Rowntree’s ads were ever-more-ingenious attempts to tie consumers’ desires for sex and status to products like After-Eights.

Harris’ products – like Kit-Kat, still the biggest-selling chocolate bar in the world – helped to save Rowntree’s. His business-stye was not particularly Quaker, he was more of an authoritarian, although he did keep the welfare / well-being side of the company going (unlike Nestle’s, who closed most of the adult education and well-being facilities in the 1990s).

4) So what we can take from Quakernomics today?

– Try to run companies as mutual enterprises – not necessarily by mutualizing, but by facilitating discussions, suggestions and group activities with all levels of the company. Strive for fair pay for all levels of the company, and make sure your suppliers’ values are aligned with your own.

– Provide opportunities for employees to broaden their minds, like Rowntree’s adult schools, the Google Campus, or the Saracens personal development programme.

– Support employees’ well-being through online and one-to-one advice, which should be entirely confidential rather than a means to spy on staff. Connect well-being services both to broader adult education (like Google’s Search Inside Yourself course) and to wider philanthropy and CSR.

– Provide opportunities for employees to pursue philanthropic activities and to feel they are working for a company with a moral mission.

– Provide opportunities for dissent, for disagreement, for satire and internal criticism – to make sure a strong collective ethos doesn’t turn into a cult!

– Explore new models of ownership which don’t make the company a slave to short-term shareholders.

– Combine moral mission with empirical rigour – what works, both for the company and for employee well-being? What sort of philanthropy or social reforms genuinely work, rather than simply making the giver feel good? Joseph and Seebohm Rowntree were both more than mere do-gooders. They were scientific in their do-gooding.

– Finally, a commitment to employee well-being is entirely in line with a commitment to business excellence, although companies can expect some dilemmas and tough decisions along the way. The moral mission needs to be led by CEOs at the top, rather than Corporate Social Responsibility reps in the middle.