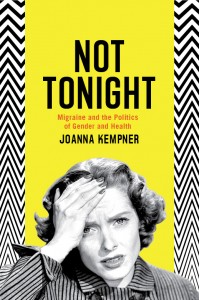

This is a guest-post by Joanna Kempner, assistant professor of sociology at Rutgers University and the author of Not Tonight: Migraine and the Politics of Gender and Health.

Are people with migraine more emotionally vulnerable? They are if we believe the stereotype: a woman, hand-pressed hard against her head, whose neurotic and possibly malingering personality makes her incapable of handling even the most basic stressors. This is the migraine sufferer encoded in dozens of misogynist jokes, each of which implies that women with migraine are either lying to avoid sex or are so weak that they succumb when faced with the prospect of working.

Are people with migraine more emotionally vulnerable? They are if we believe the stereotype: a woman, hand-pressed hard against her head, whose neurotic and possibly malingering personality makes her incapable of handling even the most basic stressors. This is the migraine sufferer encoded in dozens of misogynist jokes, each of which implies that women with migraine are either lying to avoid sex or are so weak that they succumb when faced with the prospect of working.

Even neurologists, the specialty designated with the treatment of migraine, report that they think of migraine patients as having more emotional problems than other patients. As Joan Didion famously wrote: “All of us who have migraine suffer not only from the attacks themselves but from this common conviction that we are perversely refusing to cure ourselves by taking a couple of aspirin, that we are making ourselves sick, that we “bring it on ourselves.””

All of which is why headache advocates are fighting hard to convince doctors, policy makers, and the public that migraine is a neurobiological disease and not a problem of outsized emotions. But, as I describe in my new book, Not Tonight: Migraine and the Politics of Gender and Health, the trouble is that this strategy isn’t working.

Counterintuitive as it may seem, brain-based explanations haven’t been able to undo the immense stigma attached to migraine, in large part, because this stigma is deeply embedded in a medical history that has conflated migraine with emotional instabilities.

‘Nervous temperaments’

For example, in the 19th century, the migraine patient had a “nervous temperament” and was described as irritable, nervous, susceptible, and/or hysterical. Victorian doctors made few distinctions between mind and body, so the problem was located in their nervous systems– as one influential lecturer, PW Latham, put it, they have “brains [that] are very excitable, their senses acute, and their imaginations free.” Women were more likely to have these weaker, finer, more delicate nerves. Hence, we get the Victorian woman reclining on a chaise longue with her hand pressed against her forehead.

In the mid-20th century, Harold G. Wolff, a neurologist who is now considered the “father of modern headache medicine,” changed this paradigm when he argued that migraine was the model psychosomatic disease. He began by cleverly demonstrating that the pain of migraine was rooted in the body — specifically the vasodilation of cranial nerves. But he also argued that the body responded to emotions and personality—“Loves Hates Fears,” he argued “are as real as management of lump [sic] in the chest or pus in the pericardium.”

When describing a male patient, Wolff described the migraine personality as an ambitious, successful, and efficient perfectionist who would get migraines as he grew increasingly weary, resentful, and anxious. However, Wolf described his female patients differently. Her frustrations came from sexual dissatisfaction and an unwillingness to accept maternal duties. Wolff’s contemporaries took this characterization even further. Walter C. Alvarez, for example, described his female migraine patients as “overworking or worrying or fretting, or otherwise using her brain wrongly.” Again, images of the chaise longue are conjured.

One can see, then, why contemporary headache doctors are so keen to move away from this model of headache medicine and towards a neurobiological paradigm. Unfortunately, if you look closely at the language that headache doctors use to describe the “migraine brain” you can see why their strategy is failing. The language of emotions and patient-blaming remains. And perhaps more importantly, the language of femininity remains as well.

Take, for example, this excerpt from the self-help book The Migraine Brain by headache specialist Carolyn Bernstein and Elaine McArdle:

Like a thoroughbred racehorse or diva, [the migraine brain is] hypersensitive, demanding, and overly excitable. It usually insists that everything in its environment remain stable and even-keeled. It can respond angrily to anything it isn’t accustomed to or doesn’t like.

Bernstein and McArdle’s move is to destigmatize migraine by displacing personal responsibility for the sensitivity that comes along with migraine. But Bernstein and McArdle make a tactical error: the migraine brain, here, has become a neurobiological explanation for many of the same personality quirks that have always been ascribed to those with migraine—a tendency to demand that environments change to the migraine patient’s desires, rather than a stoic ability to adjust to the changing world. Moreover, brain-based explanations remain feminized – the brain is a diva that is hypersensitive, and demanding. Just like a woman, she is. A woman giving orders from a chaise longue.

Beyond gendered diagnoses

The truth is that the relationship between mind and body in migraine is complex. Migraine symptoms can include emotional volatility and emotional swings can trigger migraine. Efforts to separate the physical from the psychological are doomed to fail. In fact, I think Latham did a better job describing this relationship in the 19th century than contemporary physicians are doing now.

What I’d like to see is more effort put into changing the public face of migraine – let’s see less gendered (and, let’s face it, sexist) representations of migraine and more emphasis put on the real pain and suffering that migraine causes.

Follow Joanna Kempner on Twitter @joannakempner

References

Alvarez, Walter C. “The Migrainous Woman and All Her Troubles.” Alexander Blain Hospital Bulletin 4 (1945): 4-5.

Bernstein, Carolyn, and Elaine McArdle. The Migraine Brain: Your Breakthrough Guide to Fewer Headaches, Better Health. New York: Free Press, 2008: 40.

Didion, Joan. “In Bed.” In The White Album, 168–72. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1979.

Latham, Peter W. On Nervous or Sick-Headache: Its Varieties and Treatment. Cambridge: Deighton, Bell, 1873: 15.

Wolff, Harold G. papers. “Lecture notes.” New York Weill Cornell Medical Center Archives, “Box 15, Folder 2.” New York, NY.