![]() One of the things I want to argue in my next book is that ecstatic experiences have been pathologised in the secular west, to our detriment. People still experience ecstasy – by which I mean moments where we go beyond the self and feel connected to something bigger than us, usually a spirit but also sometimes another individual or group – but we lack the framework to make sense of such experiences. And, as Aldous Huxley said, ‘if you have these experiences, you keep your mouth shut for fear of being told to go to a psychoanalyst’ – or, in our day, a psychiatrist.

One of the things I want to argue in my next book is that ecstatic experiences have been pathologised in the secular west, to our detriment. People still experience ecstasy – by which I mean moments where we go beyond the self and feel connected to something bigger than us, usually a spirit but also sometimes another individual or group – but we lack the framework to make sense of such experiences. And, as Aldous Huxley said, ‘if you have these experiences, you keep your mouth shut for fear of being told to go to a psychoanalyst’ – or, in our day, a psychiatrist.

The medicalisation and pathologisation of ecstasy happened slowly over the last four centuries – it is a key shift in the emergence of secular society. Before the 17th century, if you had an ecstatic experience, you might either be canonized or demonized. Either way your experience was carefully defined and controlled by the Church, which has always been wary of unbridled ecstasy, particularly in women (see Monsignor Ronald Knox’s misogynistic Enthusiasm (1950) for a recent example – Knox writes ‘the history of enthusiasm is largely the history of female emancipation…and it is not a reassuring one’).

Then, from the 17th century on, cases of both ecstasy and possession were viewed not as spiritual encounters but as disorders of our mechanical body, the product of diseased nerves, or an over-heated brain, or ‘animal spirits’, or ‘the vapours’. In the 19th century, unstable women were increasingly diagnosed with ‘hysteria’, a disease which Egyptians suggested, back in 1900 BC, was caused by a ‘wandering womb’ (supposedly the womb could be lured back to its proper position by holding scented objects near the affected woman’s vagina).

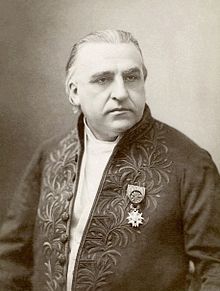

The understanding of hysteria didn’t advance much in the 4000 years to 1856, when Charcot was made head of the Salpetriere hospital in Paris. Salpetriere was the biggest hospital for women in Europe, and a ‘grand asylum of human misery’, as Charcot put it. He and his team carried out ground-breaking research into several neurological conditions – Parkinson’s, Tourette’s, Multiple Sclerosis, Lou Gehrig’s syndrome – but it was his work on hysteria that made Charcot globally famous.

The understanding of hysteria didn’t advance much in the 4000 years to 1856, when Charcot was made head of the Salpetriere hospital in Paris. Salpetriere was the biggest hospital for women in Europe, and a ‘grand asylum of human misery’, as Charcot put it. He and his team carried out ground-breaking research into several neurological conditions – Parkinson’s, Tourette’s, Multiple Sclerosis, Lou Gehrig’s syndrome – but it was his work on hysteria that made Charcot globally famous.

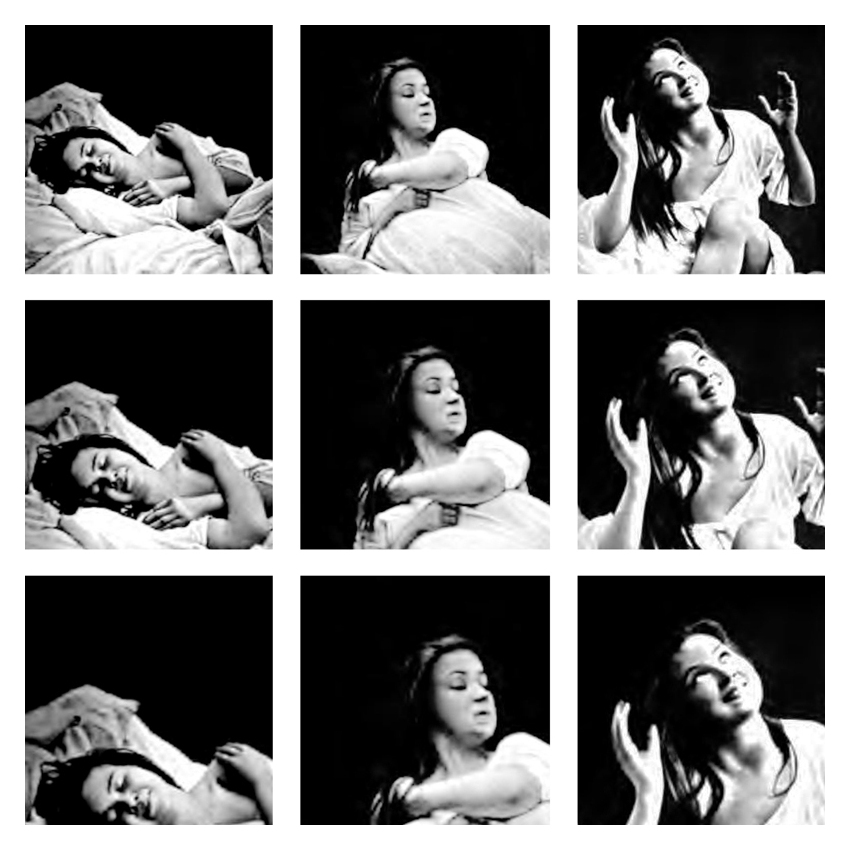

Hysteria was a notoriously loose and imprecise diagnosis, so Charcot attempted to classify it, and discover the physical cause of it. He insisted that hysterical fits followed four clearly-defined stages – 1) epileptoid fits, 2) ‘the period of contortions and grand movements’, 3) ‘passionate attitudes’, and 4) final delirium.

He claimed that, although hysteria was a physical disease caused by a lesion on the brain, one could artificially induce these four stages through hypnosis. To prove this, he used photography to capture the four stages of hysteria, and circulated the evidence through the Iconographie Photographique de la Salpetriere. Photography was still a new, somewhat magical science – rather like neuro-imaging today – and these photos ‘did much to fix the image of hysteria in the public mind’, according to the medical historian Andrew Scull.

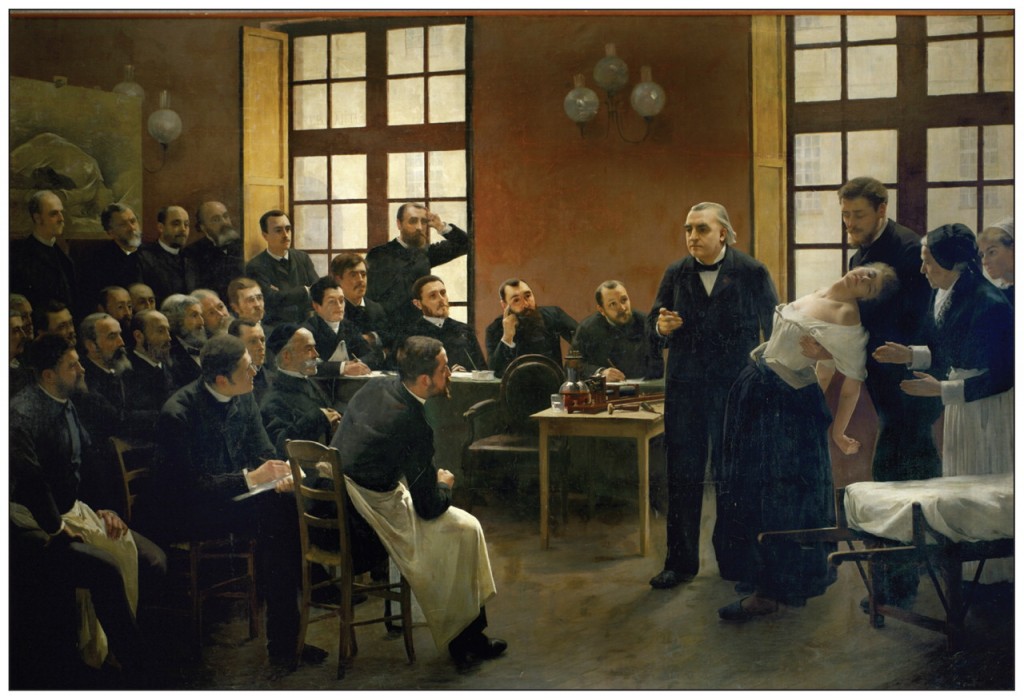

Charcot also put on public displays, every Thursday, where he hypnotized female patients and provoked hysterical fits for the fascinated male public, which included everyone from Sigmund Freud to Emile Durkheim. Both in the photographs and in the public displays, Charcot had ‘star patients’ who were particularly good at performing the four stages of hysteria, including a pretty teenager called Augustine, and a devout woman called Genevieve.

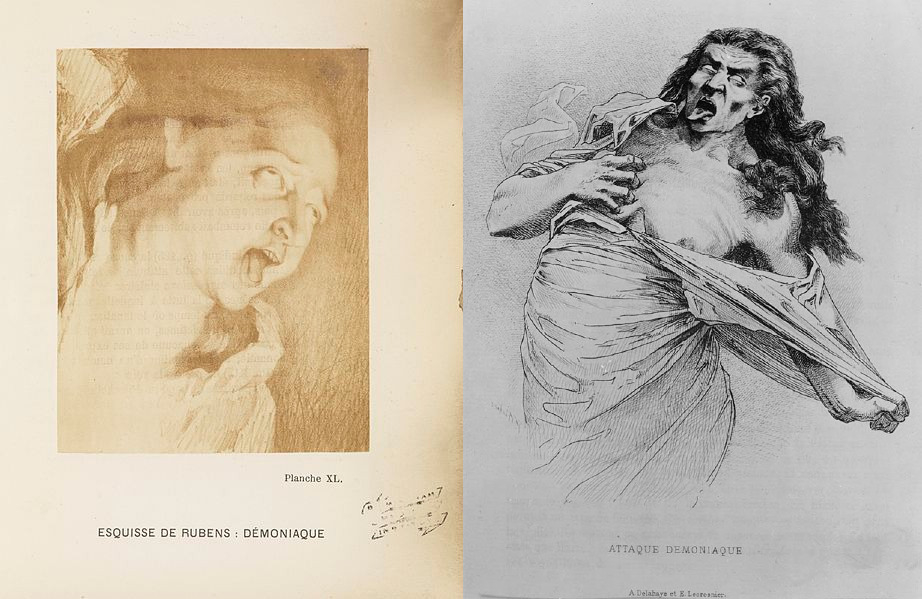

These ladies expertly performed religious poses which Charcot’s team defined as ‘ecstasy’. And the team insisted that their work proved that all the religious ecstatics and demoniacs of yesteryear were suffering from hysteria. Joan of Arc, St Theresa, St Paul, Jesus himself were all evidently hysterics. By a happy coincidence, Genevieve – who suffered from particularly violent fits – came from Loudun, the scene of a mass demonic possession of nuns in the 17th century. Charcot had an extensive gallery of religious art, and displayed the drawings and photos of his hysterics next to this art – were they not one and the same condition?

This equation of ecstasy with degenerative hysteria served a political purpose. Charcot and his disciples (particularly his main disciple, Desire-Magloire Bourneville) were closely affiliated with the Third Republic, which was virulently anti-monarchist and anti-clerical. Charcot and Bourneville were involved in the campaign to secularize medicine, and to replace nun-nurses with secular nurses. Each proof of the hysterical pathology of religious ecstasy was a broadside in this wider war.

Yet the irony, as several historians of hysteria have noted, is that in many ways the secular diagnosis of hysteria recalled the medieval Inquisition. Of course, none of the hysterics were burned – although they could be subject to physical punishments including mustard baths and ‘ovarian compression’. But they were made to follow and perform a cultural script defined and directed by a male power system, for the prurient consumption of a fascinated male public.

Again and again, the women would be made to perform hysteria, just as the poor nuns of Loudun were wheeled out, over and over, to go through their demonic antics. They would literally be fixed into poses, like ‘automatons’ or ‘statues’ as Charcot’s disciples put it, and then the poses were used as evidence for the pathology of ecstasy. This script advanced the career ambitions and political agenda of the men in charge, as it did in the Inquisition.

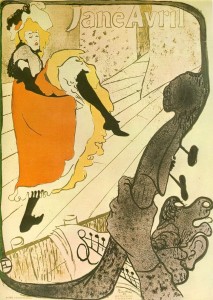

As with the Inquisition, it sounds like a form of pornographic cabaret masquerading as a public service. The Iconographie looks like a porn catalogue, with the photos of the sexy teenager Augustine interspersed with accounts of her sexual reveries. And the Thursday shows sound like something from the Moulin Rouge – the women are hypnotized by a gong or a tom-tom drum, the approach of the hysterical fit announced by the shaking of the feathers in their hats, before they fall to the floor clutching their vaginas as the male audience applaud.

Indeed, one of the star-hysterics of the Salpetriere went on to become Jane Avril, a lead-dancer at the Moulin Rouge who was painted by Toulouse-Latrec. She claimed she was cured when she learned to dance, which goes back to the ancient Greek idea that the best cure for anxiety and phobia, particularly in women, is the ‘Dionysiac cure’ of dancing. Augustine, meanwhile, finally escaped from Salpetriere, dressed as a man, while Genevieve was offended one day by Charcot and refused to be hypnotized anymore.

Indeed, one of the star-hysterics of the Salpetriere went on to become Jane Avril, a lead-dancer at the Moulin Rouge who was painted by Toulouse-Latrec. She claimed she was cured when she learned to dance, which goes back to the ancient Greek idea that the best cure for anxiety and phobia, particularly in women, is the ‘Dionysiac cure’ of dancing. Augustine, meanwhile, finally escaped from Salpetriere, dressed as a man, while Genevieve was offended one day by Charcot and refused to be hypnotized anymore.

Charcot’s search for a materialist cause for hysteria ultimately failed, and the consensus grew that his fantastic shows were merely the result of suggestion. It didn’t help that something like 500 hypnosis vaudeville shows sprang up around Paris in the 1880s, some featuring women fresh from their debut at the Salpetriere. But a few in the audience – including Sigmund Freud and Frederick Myers – still thought he had hit on something important.

If nothing else, Charcot’s use of hypnosis showed the profound connection between mind and body – his hypnotized patients felt no pain, and their physical symptoms could sometimes be cured by hypnosis and suggestion. His work suggested the existence of what Myers called a ‘subliminal self’, which could be brought to the surface under hypnosis. And it suggested a connection between spirituality, sexuality and subliminal or hypnotic states.

However, Charcot – and, later, Freud – defined hysteria purely as a symptom of female sexual disorder, when it could be argued it was just as much a product of male sexual disorder. Many of the hysterics had been raped as children or teenagers, and were struggling in a society dominated by men with few opportunities for female liberty. Performing sexual hysteria for a titillated male public was one opportunity for approval, expression and a sort of fame.

Frederick Myers, founder of the Society of Psychical Research and gifted writer on psychology (alas all his works are now out-of-print)

Frederick Myers and William James, meanwhile, accepted the idea that spirituality might be connected to sexuality, to hypnotic or subliminal states, and to nervous instability. But they insisted it wasn’t necessarily pathological or degenerative – many of the geniuses of human culture were ecstatics, much of our culture is the product of ecstasy. Perhaps, wrote Myers, ‘ecstasy is to hysteria somewhat as genius is to insanity’.

In fact, as Asti Hustvedt argues in her excellent Medical Muses: Hysteria in 19th Century Paris, in seeking to pathologize ecstasy, Charcot ended up spiritualizing medicine. He used the language of religion – ecstasy, stigmata, possession – and also some of the ritual and performance of religion. He and his disciples explored how hypnotized women seemed to exhibit miraculous powers of telepathy (a word Myers later coined).

By the end of his career, Charcot, like William James, came to recognize that religious ritual could be powerfully healing, even if the mechanism that healed was really ‘just’ suggestion. His last work, an article on ‘the faith cure’, suggests the miracle cures at Lourdes and elsewhere are real, but simply the result of suggestion. James and Myers went further, speculating that the hypnotized self might also be more open to spiritual forces.

We still don’t know. Hustvedt notes that, while ‘the hysterics of yesteryear’ have disappeared, a new batch of poorly-understood and possibly psychosomatic illnesses have proliferated – chronic fatigue syndrome, ME, post-viral fatigue, cutting, anorexia, conversion disorder, depression, psychogenic non-epileptic seizures, mass psychogenic illness – the prevalence of which is higher, sometimes much higher, in women than in men.

Are these real or invented? Physical or mental? Pathological or spiritual or both? We still don’t know. We don’t yet understand the relationship between mind and body, between mind and gender, between your mind and my mind, and between our minds and nature / God / Super-consciousness.

One last item in this bizarre and fascinating history: the vibrator was invented in the late 19th century as a result of the ancient theory that female orgasm (or ‘paroxysms’) helped to cure hysteria. Doctors would bring patients to paroxysm by manipulation, but complained their hands got cramp, so one bright spark invented an electric dildo. Meanwhile the first electrically-vibrating bed was actually developed as part of an 18th-century sexual-religious-health show called the Temple of Health and Hymen – where the star-performer was the delectable Emma Hamilton.

One last item in this bizarre and fascinating history: the vibrator was invented in the late 19th century as a result of the ancient theory that female orgasm (or ‘paroxysms’) helped to cure hysteria. Doctors would bring patients to paroxysm by manipulation, but complained their hands got cramp, so one bright spark invented an electric dildo. Meanwhile the first electrically-vibrating bed was actually developed as part of an 18th-century sexual-religious-health show called the Temple of Health and Hymen – where the star-performer was the delectable Emma Hamilton.

Don’t you think this would all make a brilliant musical?

Want to read more on this topic? Here’s a piece on mass psychogenic illness as depicted in the forthcoming film The Falling. And here’s a personal account on being diagnosed with Psychogenic Non-Epileptic Seizures by a friend of the Centre.