Dr Sally Holloway and Jane Mackelworth report on the second meeting of their community book group, exploring love and its history through literature…

The second meeting of our ‘Reading Emotions’ book group focused on Mary Hays’ semi-autobiographical novel Memoirs of Emma Courtney, published in two volumes in 1796. Hays (1759/60-1843) was born into a Dissenting family of middling status in Southwark. She saw herself as being ‘sheltered too much’ in the family home ‘like a hot-house plant’.[1] In 1792, a friend sent her a copy of Mary Wollstonecraft’s landmark treatise A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, which she embraced as ‘a work of full truth and genius’.[2] Hays marked up passages where Wollstonecraft attacked the subordinate position of women, and their trivialization in being denied education and exercise, then blamed for being physically and mentally weak.[3] She then contacted the author to thank her and seek guidance on her own works, becoming one of her most ardent disciples. The themes of female education, agency and proscribed conduct play out in Hays’ first novel.

Memoirs of Emma Courtney traces the heroine’s passionate and obsessive love for her unattainable friend Augustus Harley in part through a series of letters to him. We selected this book for our group because the heroine breaks convention in her bold pursuit of love, and is unlike the Elizabeth Bennett or Elinor Dashwood character types who readers may be more familiar with. Emma pursues Augustus determinedly through both volumes, repeatedly declaring her love and demanding to know ‘Is your heart, at present free?’[4] In one eight-page letter, she sets out the four possible ‘mysterious obstacles’ that could prevent their union: that he loved another, did not love her, had insufficient funds to marry, or sought a woman of fortune.[5] Members of our group noted that in modern Britain such behaviour could lead to the threat of a court injunction or restraining order.

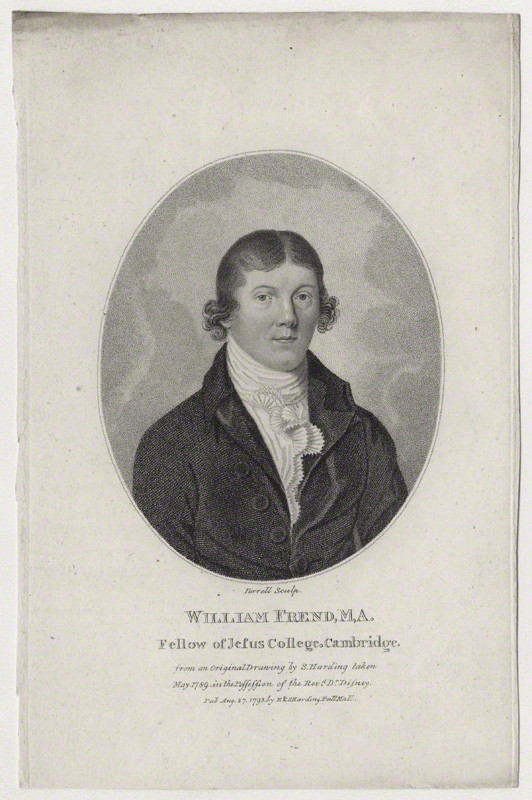

Emma Courtney’s letters are both inspired by and taken verbatim from genuine missives Hays exchanged with her friend and mentor William Godwin (1756-1836) and the Cambridge mathematician William Frend (1757-1841). Her friendship with Frend began on 16 April 1792, when he wrote to her expressing his admiration for ‘Eusebia’.[6] She confessed her love to him in 1796, but was rebuffed. On the advice of Godwin, Hays channelled her disappointment into a novel, just as her heroine creates a manuscript to ‘beguile my melancholy thoughts’.[7] The resulting novel is a faintly disguised tale of Hays’ pursuit of Frend. It introduced our members to the interconnected nature of early novels and the world of letters, as letters and prose are interspersed throughout the story.

The object of Hays’ affection William Frend. Stipple engraving by Andrew Birrell, after Silvester Harding, 1793, National Portrait Gallery, London.

The novel explores the symptoms and characteristics of Emma’s (seemingly) unrequited love. Members of our group commented that the intensity of Emma’s ‘love’ can be seen as representative of anger, frustration or repressed rage, in part due to women’s position, and lack of choice, in society at this time. It is not necessarily Augustus that she desires, but love itself. Emma is desperate to be beloved. She falls for his portrait miniature before Augustus is even present:

You may tell me, perhaps, “that the portrait on which my fancy has dwelt enamoured, owes all its graces, its glowing colouring – like the ideal beauty of the ancient artists – to the imagination capable of sketching the dangerous picture”. – Allowing this, for a moment, the sentiments it inspires are not the less genuine.[8]

Her paramour almost partakes in their romance in absentia. After discovering he was already secretly married, Emma ‘shrieks’ when confronted with his portrait, and falls ‘lifeless’ into the arms of a friend.[9]

Emma’s behaviour flouts prescribed feminine conduct, seeking to free herself from the ‘magic circle’ which maintained a ‘powerful spell’ over her sex.[10] As Hays’ biographer Gina Luria Walker argues, Emma ‘cares less for chastity and constancy than for self-fulfilment’.[11] She rejects needlework in favour of romances which fuel her sensibility. There are rumours circulating around the neighbourhood that Emma has eloped with her mentor Mr. Francis due to the partiality she shows him, which leads to her ejection from her uncle’s estate Morton Park. Emma brazenly asks both Mr. Francis and Augustus Harley to correspond with her, which was understood to invite a romantic attachment.[12]

Members of our book group felt that the intense interiority of the novel makes it a difficult read. Characters such as Emma’s father are simply used to move her onto the next stage of the plot. Even Augustus remains a shadowy character, and readers are left with little impression of his personality. Much like a diary or journal, characters are presented in terms of the impulses they stir in the heroine. Readers compared the text with modern autobiographical-style works such as Helen Fielding’s Bridget Jones’s Diary (1996), where the protagonist obsesses at length about her romantic entanglements. They agreed with the author’s reasoning that her heroine lacked an occupation or profession in which to channel her energy.

Our readers disagreed about Hays’ purpose in writing the novel; was she writing for herself or for readers? Was she criticising romantic fiction and its perceived impact on women, or partaking in romantic fantasies herself?[13] In the novel, Emma discovers on Augustus’ deathbed that he had loved her all along. In reality, Hays remained unmarried, while Frend married Sara Blackburne in 1808. Some saw the novel as a way for Hays to work through her own feelings, allowing her to make sense of her own disappointment and justify her pursuit of Frend. Luria Walker has argued that ‘Hays’ first impulse as a nascent scientist without credentials, colleagues or laboratory was to investigate herself’.[14] Having said this, Hays ultimately remains non-critical of her own behaviour.

Others understood the novel predominantly as a warning of the dangers of overindulged sensibility. Emma’s obsession is often portrayed in an unsympathetic light. As Hays notes in the preface, Emma is supposed to be a flawed human being: ‘the errors of my heroine were the offspring of sensibility; and that the result of her hazardous experiment is calculated to operate as a warning, rather than as an example’.[15] Scholars have argued that Hays intended to use the heroine’s place in society to demonstrate ‘how deeply and pervasively we are shaped by our social institutions and experiences’.[16] Emma’s sensibility is a result of her education, and the limited opportunities available to her within the ‘magic circle’. She has been ‘rendered feeble and delicate by bodily constraint, and fastidious by artificial refinement.’[17]

Contemporary reviews of the novel varied significantly according to their politics. For conservative publications such as the English Review and Anti-Jacobin Review, it was ‘in all points reprehensible, in the highest degree’. Worst of all was Emma’s offer to live with Augustus as his mistress, affording her love for him the same status as that of his wife:

If such a sentiment does not strike at the root of everything that is virtuous, that is praise-worthy, that is valuable, in the female character, we are at a loss to discover by what wickedness they are to fall.[18]

Friends reassured Hays that these hostile reviews were the work of ‘some narrow-hearted bigot, who is a sworn enemy to Mrs. Wollstonecraft and her disciples’.[19] More liberal publications such as the Monthly Magazine – to which Hays was a contributor – praised the novel as ‘the production of a well cultivated and enlightened mind’.[20] The Analytical Review extolled it as ‘the vehicle of much good sense and much liberal principle’.[21]

Love in Memoirs of Emma Courtney is a capricious, unstable and destructive force. It is presented as an essential part of marriage, with Emma initially refusing to ‘marry any man, merely for an establishment, for whom I did not feel an affection’.[22] Her bold pursuit of love led both Emma Courtney and her creator Mary Hays to become viewed as ‘sexually aggressive’ women. This reputation stayed with Hays in the years after her novel was published; her enthusiasm for Godwinian philosophy was seen to have led her into ‘embarrassing and illicit sexual extravagances’.[23] After her mentor and friend Mary Wollstonecraft died in 1797, Mary Hays remained one of her most staunch defenders.

Our next session will explore love and relationships in Charlotte Dacre’s neglected Gothic novel Zofloya, or The Moor (1806), driven by the equally controversial heroine Victoria di Loredani.

Read more about the ‘Reading Emotions’ book group.

Read more posts about the history of romantic love.

Follow Sally Holloway on Twitter: @sally_holloway

Follow Jane Mackelworth on Twitter: @jane__victoria

References

[1] Letters of Mary Hays, Pforzheimer Library, New York, cited in Gary Kelly, Women, Writing, and Revolution 1790-1827 (Oxford, 1993), p. 92.

[2] A. F. Wedd (ed.) The Love-Letters of Mary Hays (1779-1780) (London, 1925), p. 5.

[3] Kelly, Women, Writing, and Revolution, p. 84, note 10.

[4] Mary Hays, Memoirs of Emma Courtney (Oxford, 2009), p. 82.

[5] Hays, Memoirs, pp. 118-125.

[6] Hays adopted this pseudonym to publish the pamphlet Cursory Remarks on an Enquiry into the Expediency and Propriety of Public or Social Worship. Inscribed to Gilbert Wakefield (1791).

[7] Hays, Memoirs, p. 138.

[8] Hays, Memoirs, p. 82.

[9] Hays, Memoirs, pp. 150-1.

[10] Hays, Memoirs, p. 85. The term was also used to refer to the romantic imagination in Wollstonecraft’s Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark, Letter 10, p. 100.

[11] Gina Luria Walker, Mary Hays (1759-1843): The Growth of a Woman’s Mind (Aldershot, 2006), p. 146.

[12] Emma’s uncle Mr. Morton demands to know: “I will speak more plainly: – Has he made you any proposals?’, Memoirs, p. 44.

[13] Scholars have described a similar paradox in how the novel claims ‘to be a warning against the over-indulgence of feeling’ but actually ‘celebrates and validates the heroine’s own infatuated, coercive effusions’, Nicola Watson, Revolution and the Form of the British Novel, 1790-1825: Intercepted Letters, Intercepted Seductions (Oxford, 1994), p. 45.

[14] Luria Walker, Mary Hays, p. 134.

[15] Hays, Memoirs, p. 4.

[16] Brian Michael Norton, ‘Emma Courtney, Feminist Ethics, and the Problem of Autonomy’, The Eighteenth Century, Vol. 54, No. 3 (2013), p. 301.

[17] Hays, Memoirs, p. 32.

[18] The Anti-Jacobin Review and Magazine; or Monthly Political Literary Censor, Vol. 3 (1799), pp. 54-7.

[19] [John?] Evans to Mary Hays, in Wedd, Love-Letters, pp. 222-3.

[20] Monthly Magazine 3 (1797), p. 47.

[21] Analytical Review 25 (1797), pp. 174-8.

[22] Hays, Memoirs, p. 56.

[23] Luria Walker, Mary Hays, p. 160 and Miriam L. Wallace, ‘Mary Hays’s “Female Philosopher”: Constructing Revolutionary Subjects’ in Adriana Craciun and Kari E. Lokke (eds) Rebellious Hearts: British Women Writers and the French Revolution (Albany, 2001), p. 238.