Last Sunday I finished a 10-day Vipassana retreat, at a monastery in Sweden. This was my third attempt to do a monastic retreat – I’d done a runner from both previous efforts, from a Rusian monastery in Lent 2006 (the head monk kept trying to convert me to Orthodox Christianity) and from a Benedictine monastery on the Isle of Wight in January 2013 (I was bored). This time, I vowed not to do a runner. To make sure, I chose a Vipassana centre in the middle of the Swedish countryside. Further to run.

Last Sunday I finished a 10-day Vipassana retreat, at a monastery in Sweden. This was my third attempt to do a monastic retreat – I’d done a runner from both previous efforts, from a Rusian monastery in Lent 2006 (the head monk kept trying to convert me to Orthodox Christianity) and from a Benedictine monastery on the Isle of Wight in January 2013 (I was bored). This time, I vowed not to do a runner. To make sure, I chose a Vipassana centre in the middle of the Swedish countryside. Further to run.

The Odeshog Vipassana centre, in the south of Sweden near Lake Vattern, offers 10-day, 20-day and three-month retreats as taught by a Burmese teacher called SG Goenka, who died in 2013. The courses are all free, you offer whatever donation you want at the end of the course.

Let me sketch a brief history of Vipassana. At the beginning of the 20th century, a Burmese monk called Ledi Sayadaw made the unusual move of entrusting his teachings to a farmer called Saya Thetgyi, telling him that his mission was to teach Vipassana to laypeople. Saya Thetgi’s students included a civil servant called U Ba Khin, who was a leading figure in the post-independence Burmese government. When he wasn’t running five departments (at the same time), U Ba Khin also taught a 10-day intensive course in Vipassana to a select handful of laypeople.

In 1955, a rich Hindu businessman called SG Goenka was looking for relief from debilitating migraines. He had tried many different medical solutions, at one point living in Switzerland to consult the doctors there, and become addicted to morphine in the process. A friend suggested he try U Ba Khin’s 10-day course, but U Ba Khin told him the aim of the path taught by Buddha was not migraine relief but liberation from the ego. Goenka had his own doubts – he was a devout Hindu, and feared ‘taking refuge in the Buddha’ might be sacrilege. But eventually he was convinced that the Buddha taught a non-sectarian approach to wisdom, and he started the course. He almost did a runner on day two, but stayed, and became a great disciple. In 1971, U Ba Khin passed the lineage to him, with a mission to expand it globally. Goenka left his business, moved to India, and began setting up Vipassana centres – there are now around 170 globally – offering 10-day introduction courses and longer retreats. He was clear he wasn’t seeking to be worshipped as a guru or to convert anyone to Buddhism, but was rather teaching an ‘art of living’.

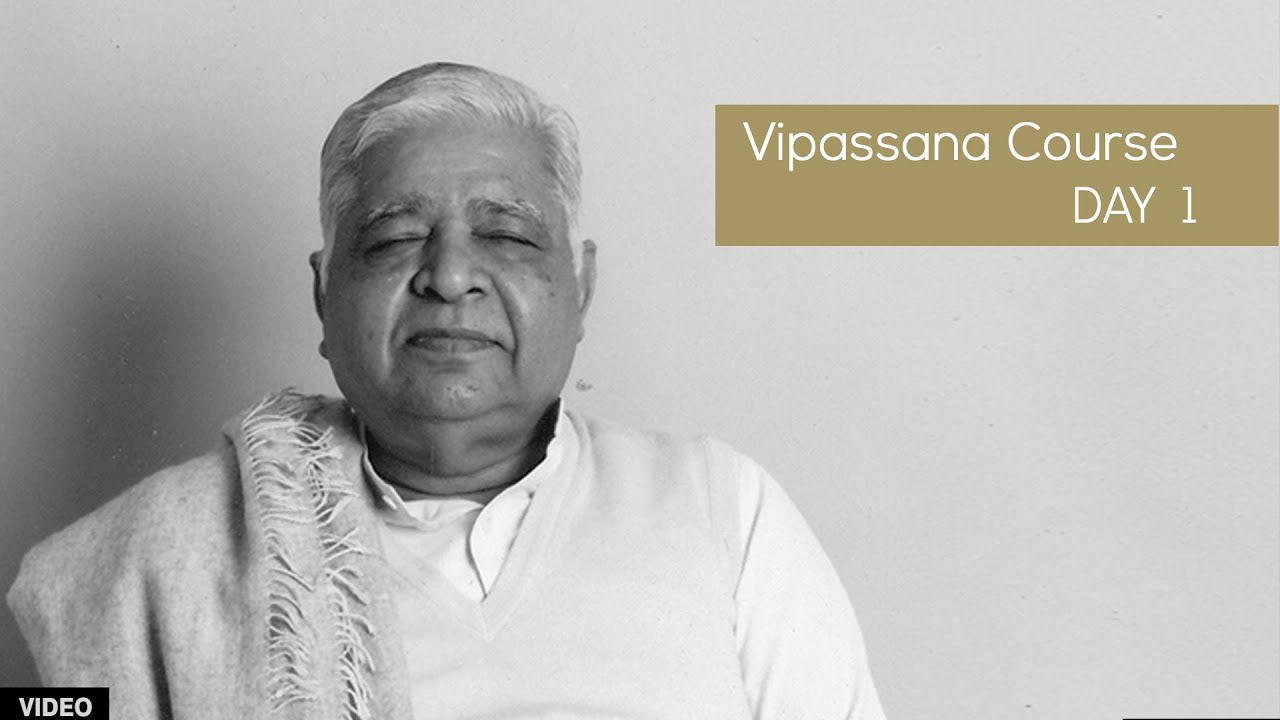

Bringing Vipassana to lay-people: Saya Thetgyi, U Ba Khin and SG Goenka, from left to right

His courses attracted several young westerners who went on to be leading figures in western Buddhism, including Daniel Goleman, Ram Dass, Sharon Salzberg, Jack Kornfield and Joseph Goldstein. Kornfield and Goldstein set up the Insight Meditation Centre in Massachussets in the 1970s, offering similar 10-day and two-week retreats partly inspired by Goenka’s structure. In the spring of 1979, a researcher at U-Mass medical school, Jon Kabat-Zinn, attended a two-week retreat at the Insight Meditation Centre. He writes:

while sitting in my room one afternoon about Day 10 of the retreat, I had a ‘vision’ that lasted maybe 10 seconds…I saw in a flash not only a model that could be put in place, but also the long-term implications of what might happen if the basic idea was sound and could be implemented in one test environment—namely that it would spark new fields of scientific and clinical investigation, and would spread to hospitals and medical centres and clinics across the country and around the world, and provide right livelihood for thousands of practitioners.

Kabat-Zinn (who was also influenced by other approaches like Zen and Tibetan Buddhism) established what became known as the mindfulness-based stress-reduction programme (MBSR), an eight-week programme drawing on Vipassana breathing awareness and body-scan techniques and also on yoga. That in turn inspired mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and other mindfulness therapeutic interventions. There are now mindfulness centres in over 35 medical schools in the US, mindfulness CBT is provided by the NHS, it’s offered at many companies from Google to the US Army, there are mindfulness apps like Headspace, and courses in everything from mindful eating to mindful colouring. Time magazine has called it ‘the mindfulness revolution’ -it’s also a $1 billion-a-year industry. All this fits in to a prophecy which Ledi Sayadaw liked to quote, that 2,500 years after the Buddha’s death Vipassana would return from Burma to India, and then spread round the world. ‘The clock of Vipassana has struck!’, he would say (along with the clock of yoga and Tibetan Buddhism).

Kabat-Zinn (who was also influenced by other approaches like Zen and Tibetan Buddhism) established what became known as the mindfulness-based stress-reduction programme (MBSR), an eight-week programme drawing on Vipassana breathing awareness and body-scan techniques and also on yoga. That in turn inspired mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and other mindfulness therapeutic interventions. There are now mindfulness centres in over 35 medical schools in the US, mindfulness CBT is provided by the NHS, it’s offered at many companies from Google to the US Army, there are mindfulness apps like Headspace, and courses in everything from mindful eating to mindful colouring. Time magazine has called it ‘the mindfulness revolution’ -it’s also a $1 billion-a-year industry. All this fits in to a prophecy which Ledi Sayadaw liked to quote, that 2,500 years after the Buddha’s death Vipassana would return from Burma to India, and then spread round the world. ‘The clock of Vipassana has struck!’, he would say (along with the clock of yoga and Tibetan Buddhism).

Military discipline

Many people also still go on Goenka’s 10-day courses. Although he died in 2013, you still hear his instructions and chanting by audio at the beginning and end of every meditation session (his baritone chanting is something to hear) and watch an hour-long dharma talk by him every evening. For 10-days, he’s pretty much the only voice you hear, besides the brief interjections from the assistant teacher, which are usually confined to ‘keep working’.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m41Mb_Mdm2w

There were 60 people on the course, 30 men, 30 women, who slept in different buildings, ate in different halls, and meditated on different sides of the dharma hall. We all agreed to follow certain rules for the 10-days: a vow of ‘noble silence’ (no talking or communicating except with the assistant teacher), no booze, no sexual misbehaviour, no phones, books or writing, and no other religious practices in order to ‘give the technique a fair trial’. We also agreed to follow the meditation schedule, getting up at 4.30am and going to bed at 9.30pm. The Buddha taught that there are three parts to the path – sila, samadhi and panya, or morality, concentration and wisdom. The vows were sila – the moral foundation without which the practice does not bear fruit. Goenka said: ’Many teachers, both in the Buddha’s time and now, offer samadhi meditation without any sila. They say it doesn’t matter what you do or how you live, just follow this practice and you’ll get the benefits. That’s not true.’ I wondered what he’d make of the mindfulness boom today.

The vows try to strengthen the 10 paramitas or virtues – Buddhism is a virtue ethics which trains people in moral habits like equanimity, tolerance and loving-kindness. The vows were hard – I missed the internet, and missed books and writing even more. The silence I could handle, but I realized I am very intolerant – a few times, I muttered at my room-mate when he disturbed my sleep.

And then there was the meditation. On the first evening, I saw the schedule of meditation, and my heart sank.

The longest I’d ever meditated before was half an hour, and I thought that was a heroic achievement. Ten hours a day? How would I ever get through it? Initially there was a lot of clock-watching and day-counting, like a prisoner trying to get through a long stretch. Ten days felt like a very long stretch.

The longest I’d ever meditated before was half an hour, and I thought that was a heroic achievement. Ten hours a day? How would I ever get through it? Initially there was a lot of clock-watching and day-counting, like a prisoner trying to get through a long stretch. Ten days felt like a very long stretch.

The first three days are focused on teaching samadhi, or concentration, through anapanasati, or concentration on the breath. We practiced focusing on our breath going in and out of our nostrils, noticing which nostril it’s going in and out of, whether it feels cold or warm etc. On Day Two, we focused on the nose area, to see if we felt any sensations there, then on Day Three, we focus just on our upper lip. Mind kept running away, of course, into the past and future – you realize how closely memory and imagination are intertwined. Often I wouldn’t realize for 10 or 20 minutes that I’d become lost in an inner movie, then I’d wake up, and bring the mind back.

Your problem-solving, outward-focused, ego-driven mind has been in charge for so long, and it keeps bringing you fascinating insights, like a wagging dog bringing you sticks, and you want to remember and preserve the insights (particularly if you’re a writer), but you don’t have pen or paper, and in any case these ‘insights’ are just a ploy by the ego-mind not to sit still, so you keep gently bringing mind back to the breath. And the strange thing is, it gets easier. By Day Three I could concentrate for a whole hour on the breath without losing focus for more than a minute or two. And I became fascinated by the sensations on the nose or the lip – there’s a whole world going on there!

Torture camp

On the evening of Day Three, Goenka told us that all this samadhi practice was to prepare us for Vipassana proper, which would begin on Day Four. We would ‘make a deep surgical incision’ into the unconscious, in order to lance the pus and begin the healing. It would be painful, it would be difficult, some weak-minded people might even do a runner (not me!). So we should prepare ourselves. On Day Four, we gathered nervously in the hall for the Vipassana ceremony. Goenka (on tape) led us through the 90-minute meditation – we should concentrate on our head, then our face, then our shoulders and arms, then our throat, then our stomach, then….It was a big let-down – firstly, he went quite quickly, so it was difficult to be aware of any sensations in one body part before he’d moved on to the next one. And secondly, wasn’t this just a ‘body-scan’? Where was this deep dive into the unconscious we’d been promised? I was pissed off after that session, annoyed with this overweight burping Burmese businessman, and all these western sheep who chanted ‘sadhu’ (agreed) after his Pali singing, even though they’d no idea what they were agreeing to.

Things got harder in the next session. We were told there was a ‘new rule’ – the three hour-long group meditations each day were henceforth ‘sittings of great determination’, in which we should try not to move for the whole hour. For some masochistic reason, I decided to do these sittings cross-legged, even though I could barely sit cross-legged for ten minutes (because of a skiing injury in my left leg). For all of us, these sessions were intensely uncomfortable and painful. We were told to simply be aware of whatever sensations arose – whether gross (painful) or subtle (pleasurable) – and observe without attachment or aversion. This would overcome our deep-seated ego-habit to react to physical sensations with craving or aversion, which was at the root of all our suffering.

So you would sit there, doing these circuits round the body, from head to toe and toe to head. I’d do roughly four circuits in an hour. The pain in my legs, thigh and buttocks would start around mid-way through circuit two, at the 20 minute mark. By 30 minutes it was quite painful. By 45 minutes it was agony. During the last five minutes, my body would be shaking from the pain, there’d be tears in my eyes, a feeling of nausea, I’d only be conscious of the pain, in my knee or feet or buttock or thigh, stabbing, awful, unbearable pain. So I’d give up, unlock my legs, and the pain would vanish. We went through three of these torture-sessions a day.

Since the development of anaesthetics, we have lost the idea of pain as educative or ennobling, as Ariel Glucklich explores in ‘Sacred Pain’

Why put myself through this pain? Surely there was nothing ennobling about it, it was just my body warning me I’d injure myself. We were told that observing gross sensations without aversion ‘purified’ the accumulated sankharas (habits of craving and aversion) of the past. We would also learn that both gross, solidified sensations and subtle sensations were anicca, or impermanent – they arose and passed away. The sensations might be fast pleasant treble vibrations or slow painful bass vibrations, but they were all part of the same cosmic song of anicca. This realization would liberate us. Really? Or was I just doing permanent damage to my legs?

Transcending aversion

On Day Six, I managed to get to the hour-mark without moving, dragging myself grimly round four body-circuits, my body quivering with the effort, until Goenka’s chanting comes in to mark the hour point, you praise the Lord for the end, and go to your room feeling sick. And then, on Day Seven, something strange happened, in the first ‘sitting of great determination’, about 40 minutes in. The pain was building up, I was observing it and reminding myself it was impermanent, and then something shifted. It was like a light dawned within me, literally, and a cool breeze spread over the top half of my body. It felt like cool vibrations went all through the top half of my body, which were sufficiently pleasant that I no longer felt bothered by the pain in my legs. And then, when I observed the ‘gross sensations’ of pain in my legs, which seemed so solid and permanent, they dissolved too, into subtler sensations. My left foot, which had been totally asleep in a deep freeze, also woke up. Everything in my body dissolved – everything except my left buttock, which remained stubbornly clenched. I observed it, willing its dissolution, but it wouldn’t dissolve, it held out.

Still, it was a breakthrough. It felt like the chemical creation of some new substance through transcending pain. GI Gurdjieff, from the Pythagorean-Platonic tradition (supposedly inspired by Pythagoras’ journey to India), also talks about purifying oneself through the alchemical process of ‘intentional suffering’: ‘One needs fire. Without fire, there will never be anything. This fire is suffering, voluntary suffering’. After this, the sessions became easier, though it was not linear progress – sometimes I’d have a great session, and decide I’d become a very wise and advanced being, and then the next session I’d wipe out after thirty minutes. It was constantly humbling and humiliating. But I learned three main things.

The physical unconscious

Firstly, I learned that pain is intimately connected to aversion. When I’d briefly overcome aversion and find an attitude of acceptance or equanimity, it transformed the pain. When a strong aversion-thought came back, like ‘you’re not going to make it!’, the pain would spike instantly. Insight also transformed the pain – if I reminded myself that the pain was not permanent, not solid, that it rose and fell, shifted, was transient, this helped to dissolve a very solid concrete feeling into a subtler sensation. One particularly noticed this with some of the solid habitual muscular tension we carry around – insight would dissolve these muscular knots, in a fascinating way. The body and mind are intimately connected in a way we don’t yet fully appreciate. States of deep absorption connect to our muscles, autonomic nervous system and immune system in ways that can be profoundly physically healing.

Secondly, I realized the importance of working with what Goenka called ‘the unconscious’, by which he meant our semi-conscious physical sensations. Greek philosophy and CBT also talk about overcoming our attachment and aversion to externals, and cultivating acceptance and equanimity of the endless flux of the cosmos, but the therapy of Greek philosophy / CBT is mainly focused on becoming mindful of one’s thoughts. The focus is mainly cognitive. Vipassana, by contrast, teaches mindfulness mainly through the body – we become aware of our physical sensations and their impermanence, thereby transcending aversion and attachment at the physical level. I think that’s transformative at a much deeper level than Stoicism – many Stoics, including me, might be quite rational at the thought-level, but still basically stuck in attachment and aversion at the subconscious physical level. Vipassana also introduces the idea of karma – sometimes, we may have a sudden physical sensation of, say, pain or anxiety or heaviness, and it may not be related to a present situation, but may rather be a manifestation of a past craving or aversion. So sometimes depression or anxiety simply manifests from the past, and there’s no point looking for the event that triggered it, one just has to note it, and note it won’t last forever. Belief in reincarnation means Buddhism (like Pythagorean-Platonism) is more optimistic than Stoicism – we don’t just endure suffering out of acceptance of the Logos, we endure it and purify it bringing us the promise of liberation in future lives.

Transcending attachment to ecstasy

Finally, I glimpsed a new attitude towards ecstatic or altered state experiences. I wouldn’t say I had an ecstatic experience on the course, it was harder than that. But some of my fellow students did – one girl, who gave me a lift back to Gothenberg, told me about her first retreat, where she felt really high the entire 10 days. Another man told me he felt a sudden shift into a sort of vast inner hall of light. A 1979 phenomenological study by Jack Kornfield found that 95% of students on a three-month retreat and 40% of students on a two-week retreat reported experiences of rapture or bliss (described as piti in the Pali texts). But students also reported painful experiences: the return of difficult emotions and traumatic memories, autonomic disfunction in breathing, shaking, insomnia, nightmarish visions of violence or orgies. Participants on my course also found it very tough at times – my room-mate said he faced the return of deeply anxious thoughts and sensations from his teenage years, and felt ‘almost psychotic’ at times. Another participant told me he’d been beset by violent visions on his first retreat.

Traditional psychiatry would tend to pathologize such experiences, good or bad. But this is a mistake, as Kornfield writes:

Unusual experiences….are the norm among practiced meditation students. Over 80% of our three-month students reported such experiences as part of their normal meditation process. From our data it seems clear that the modern psychiatric dismissal of these so-called ‘mystical’ and altered states as psychopathology – referred to as ego-regression to an infantile state or labeled as psychic disorder – is simply due to the limitations of the traditional Western psychiatric mental-illnesses oriented model of the mind.

We shouldn’t be averse to, afraid of or embarrassed by such experiences, as western psychiatry has taught us to be. At the same time, we shouldn’t become attached to them either. Goenka repeatedly warned that blissful or rapturous experiences were dangerous, because they could lead to craving. People end up playing ‘the sensation game’, chasing the rapture, expecting it, craving it. Laura, the girl who gave me a lift, told me her second retreat was harder than the first, because she’d been expecting the bliss, and instead there was pain. Equanimity towards both painful and rapturous experiences seems to me a much healthier attitude than one sometimes finds in, say, Transcendental Meditation, Romanticism, the New Age, or charismatic Christianity, where the sensation of transcendent bliss, rapture, shakti or kundalini can easily become fetishized as the high-point or goal. For example, in 2013 I had an ecstatic experience in a Christian context, and it was immediately seized on, turned into a ‘testimony’, and telegraphed around the church network. I was told there was a gr

We need to overcome our cultural aversion to ecstatic experiences, but we equally need to overcome the strong attachment to ecstasy often found in Romanticism, the New Age or charismatic Christianity. Otherwise we become spiritual thrill-seekers, denigrating the everyday and unprepared for the pain. As Kornfield puts it, ‘after the ecstasy, the laundry’.

So I’m back in the world now, and not sure what will survive of my practice in these less propitious circumstances. But I hope I’ll keep on sitting and observing whatever comes up. Goenka advises us to meditate two hours a day, and renounce booze and meat. We’ll see. Meanwhile, at the Odeshog centre, a new batch of students have just arrived, and are sitting down to begin the practice.