Continuing Disgust Week, in which a group of scholars from a range of disciplines explore different aspects of disgust, Benedict S Robinson explores the history of the word itself.

Continuing Disgust Week, in which a group of scholars from a range of disciplines explore different aspects of disgust, Benedict S Robinson explores the history of the word itself.

Benedict S Robinson is Associate Professor of English at Stony Brook University. His field of specialization is British literature and culture in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. His first book, Islam and Early Modern English Literature, appeared in 2007; he is currently completing a second book called Inventing Emotion in Shakespeare’s England, the first piece of which appeared from ELH under the title “Disgust c. 1600” in Summer 2014.

Disgust is often called one of the “basic” emotions, to be explained in evolutionary terms as a reaction that protects us from contamination. The word disgust, on the other hand, has a more limited history, first appearing in English around the year 1600. Noticing this a few years ago led me to speculate that disgust constructs the sphere of aversive experience differently from older terms like loathing. The results of this work, published in 2014, argued that available concepts of aversion understood it primarily in terms of what we would call moral loathing; that such accounts had little interest in mere physical revulsion; that the word loathing tended to make moral loathing paradigmatic of the whole category; and that the appearance of disgust represents a distinct way of interpreting aversion, one more likely to be concerned with the experience of physical revulsion, and more likely to construe revulsion as a problem of essentially aesthetic, hygienic, and social distinctions. In fact I traced the origins of the word to new forms of cultural capital in the expanding metropolitan London of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Histories of emotion have long leaned on language as a primary source of evidence. Such arguments always face a theoretical problem about their reach. Do all linguistic changes map changes in conceptualization? Can we draw a line—as Anna Wierzbicka has tried to do—between semantic primitives and that realm of variability that is subject to the forces of history and culture?

That problem is obviously not one I can claim to solve here. But I want to suggest that one important way forward is to expand our use of linguistic evidence. Since that 2014 article, I have been looking for ways of using digital archives to study patterns in early modern language use; and I have been looking for ways of thinking about the evidence extracted from those archives in terms provided by certain strands of cognitive linguistics. My idea is that the digital humanities and cognitive sciences are a natural fit for each other, especially if we want a history of emotion that is something other than a history of theories of emotion: a history of the ways in which people wrote and spoke about emotion across a range of social and linguistic contexts. There have been several efforts to connect corpus linguistics to cognitive linguistics, but that work has largely been based on contemporary materials: we have cross-linguistic analyses but not cross-historical ones, despite a call for the latter by Zoltán Kövecses, in his account of the metaphors that structure the concept of emotion.

Early English Books Online, the central digital archive of early printed books, is an excellent resource for pursuing this kind of work, because—by comparison with other digital archives—it is very well-curated, as the product of about a century of bibliographical scholarship. The most useful engine for studying the contents of EEBO is provided by the Corpus Query Processor at Lancaster University, which accesses about a third of the EEBO corpus. The contents of CQP are tagged with part-of-speech tags, so that one can, for instance, look for the adjectives most commonly modifying forms of disgust:

_JJ disgust*

The results show a tendency to measure disgust almost as though it were a mass noun, including measures of some degree of subtlety: “little,” “small” (Fig. 1). What disgust generally measures is social antagonism, as we can see from searches that capture the nouns that tend to constellate with it:

_NN1 _CC disgust*

disgust* _CC _NN1

_NN2 _CC disgust*

disgust* _CC _NN2 (Fig. 2)

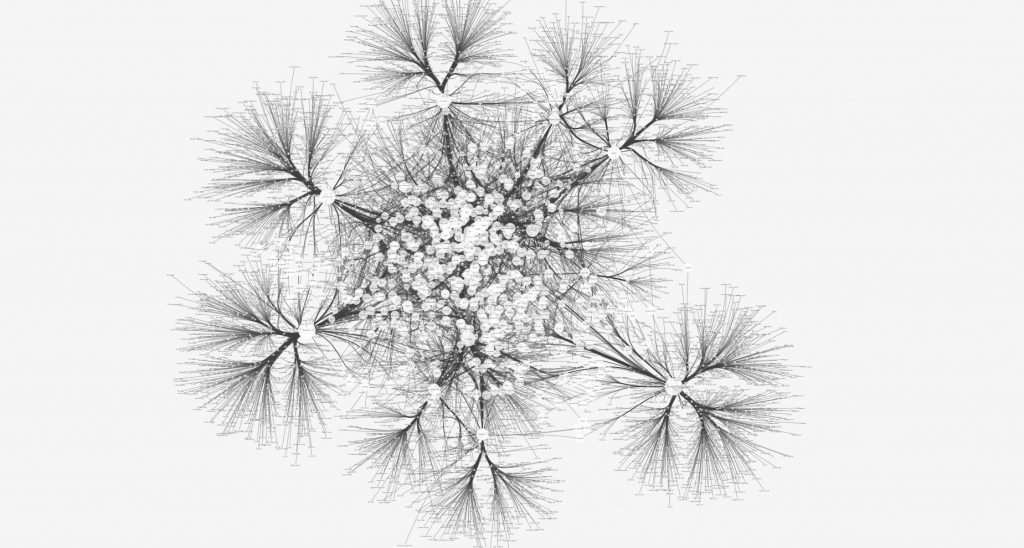

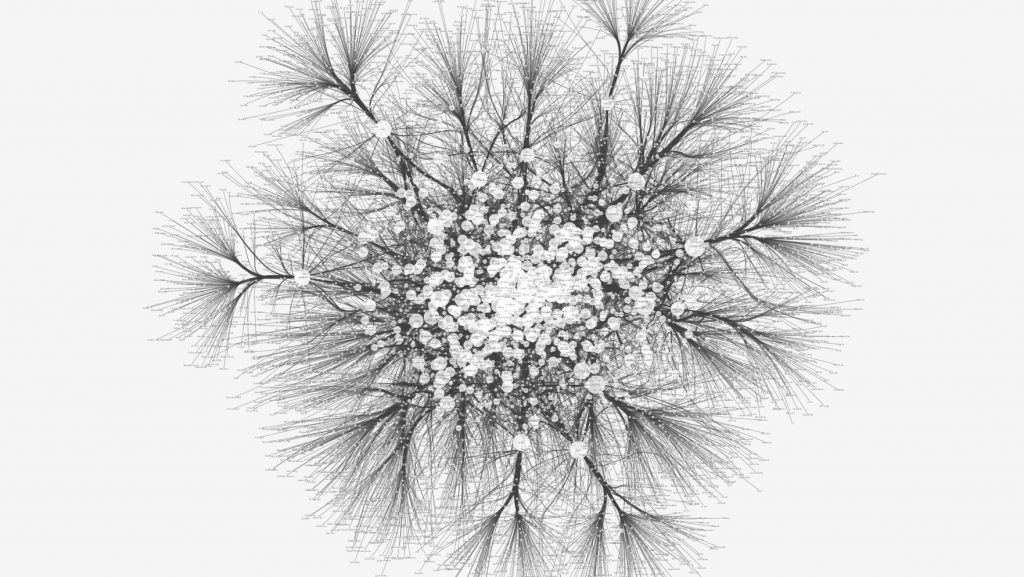

The collocates of disgust—words that co-occur with it at rates higher than we would expect based on a random distribution—confirm the link between disgust and social antagonism. The collocates of loathing, on the other hand, tend to constellate physical filthiness—indexed by reference to smell as well as taste—with some very large moral abstractions: the twelfth collocate of loathing is “sin.” In fact changes among the collocates of loathing after about 1609 suggest that the arrival of the new word may have shifted usage of the older one. The collocate lists are too extensive to include here, but they open the way to studies of idiomatic language use, even to modeling whole areas of discourse. One method I have been experimenting with is to use network analysis to investigate the multiple relations among a word’s collocates, by means of the open-source network analysis program Cytoscape (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). The results are preliminary, but they suggest that it might be possible to model lexical meaning in terms of the interaction of multiple discursive regions. The results suggest that disgust and loathing are built on distinct metaphorical construals. Disgust analogizes from bitter tastes to local social conflicts. Loathing analogizes from a repertory of loathsome objects to a language of moral corruption centered above all on sexual violations, as paradigmatic instances of the ostensible filthiness of sin.

Does all of this this indicate that disgust and loathing construe aversion in distinct ways? It may: the collocate networks for disgust and loathing only overlap about 30%.

There are no doubt other and better ways of putting EEBO to use in studying the language of emotion. But this seems to me a vital direction for future research. Pursuing it also needs to mean looking beyond emotion words—which have been at the heart of so much work on the history of emotion—toward larger constructions and toward patterns of metaphor. What is entirely clear is that if digital archives are to be effective tools for scholarship they must be based on the results of traditional humanities research. Anyone who has tried to use Google Books as evidence of anything knows what an archive looks like when it has not been curated.

Fig. 1. ADJ-N Constructions

CQP search “_JJ disgust*” (351 matches in 287 texts)

|

Search result |

Hits |

Percentage |

|

great disgust |

47 |

13.39% |

|

general disgust |

17 |

4.84% |

|

little disgust |

14 |

3.99% |

|

small disgust |

13 |

3.7% |

|

particular disgust |

12 |

3.42% |

|

deep disgust |

8 |

2.28% |

|

high disgust |

7 |

1.99% |

|

great disgusts |

6 |

1.71% |

|

secret disgust |

6 |

1.71% |

|

private disgust |

6 |

1.71% |

|

new disgusts |

6 |

1.71% |

|

new disgust |

6 |

1.71% |

Fig. 2. N-CC-N Constructions

A. CQP searches “_NN1 _CC disgust*” and “disgust* _CC _NN1” (195 matches)

|

Search result |

Hits |

Percentage |

|

discontent[ment] |

13 |

6.67% |

|

aversion / aversation |

12 |

6.15% |

|

hatred |

7 |

3.59% |

|

prejudice |

7 |

3.59% |

|

offence |

6 |

3.08% |

|

bitterness |

5 |

2.56% |

B. CQP searches “_NN2 _CC disgust*” and “disgust* _CC _NN2” (72 matches)

|

Search result |

Hits |

Percentage |

|

jealousies |

4 |

5.56% |

|

troubles |

4 |

5.56% |

|

animosities |

3 |

4.17% |

|

injuries |

3 |

4.17% |

|

insurrections |

3 |

4.17% |

|

prejudices |

3 |

4.17% |

Fig. 3. Disgust Collocate Network

Imaged via Cytoscape.[1]

Fig. 4. Loathing Collocate Network

Imaged via Cytoscape

[1] Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T. “Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks,” Genome Research 13.11 (2003): 2498-504.