This is the first of two posts about the Music and Emotions Concert held at Barts Pathology Museum and supported by the QMUL Centre for Public Engagement. Read the second on Thursday!

Late afternoon on a Monday in early October and my steps up the stone stairs to Barts Pathology Museum are accompanied by the ethereal sound of a harp, flute and violin. The music swells and pulses as I grow closer and I tiptoe through the doors to the sight and sound of the Harborough Collective rehearsing. The museum is softly lit, the musicians framed by a semi-circle of chairs, and the backdrop is very striking indeed: behind them are human-tissue specimens and watercolours showing various human pathologies. Awe-struck by the visual impact of the space, I also felt both excited and peaceful by the music…how would the audience feel in two hours time?

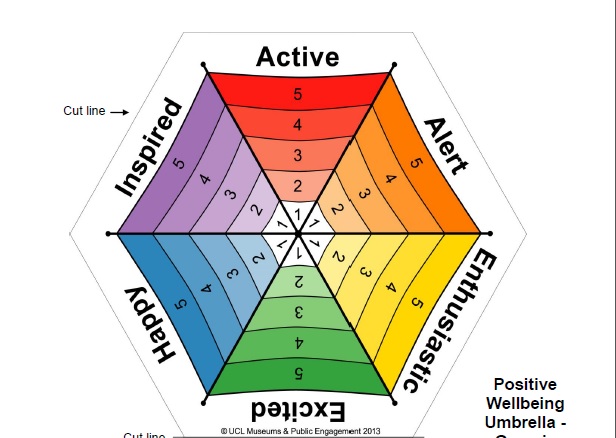

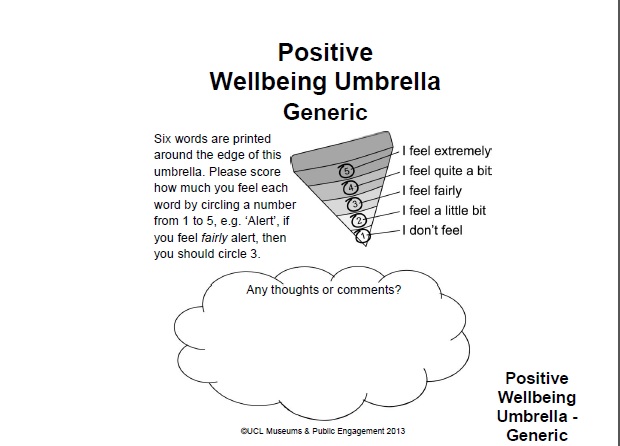

Lisa, David and Eleanor (the Harborough Collective) were rehearsing for the first collaborative event between the Centre for the History of the Emotions, the QMUL Director of Music (Paul Edlin) and Barts Pathology Museum. We wanted to investigate how listening to music might affect wellbeing and how prior knowledge of the music being played affects emotional responses. To do so, Paul and the Harborough Collective had designed a special programme of music and I had come armed with wellbeing umbrellas (pictured) and questionnaires. We would ask the audience to complete a wellbeing umbrella at the beginning and end of the concert, enabling us to trace change in wellbeing across the event, and the audience would record their emotional responses to the music at the end of each half on the questionnaire. The umbrellas were designed by UCL as part of their UCL Museum Wellbeing Measures Toolkit. I designed the questionnaire myself and it asked respondees to tick the emotions they felt during each piece of the performance (or add their own) and respond free-form to the question of whether the venue had impacted their experience of the music. In the first half, the audience would know nothing about the music being played; their responses would be shaped only by the performance, the space, and any prior knowledge they might have. In the second half, they’d be introduced to the concept of the history of the emotions and its relationship with music by researcher Dr Marie Herzfeld Schild. Dr Herzfeld Schild would also tell the audience about the music they had already heard and what they would hear in the second half.

After setting up I was treated to a personal tour of some of the museum’s specimens by Steve Moore, who oversees the museum’s pathology collections. I’d recommend a visit to the foreign objects found in human bodies case which includes a rocket removed from a man’s anus while potentially still live, hair pins, a toothbrush and a stone. I also saw trepanned skulls and tumours. One audience member apologized to me because her wellbeing umbrellas might imply she left with feeling less well than when she arrived but she assured me that this just reflected the extremely high levels of enthusiasm, excitement, and alertness (measured by the umbrellas) that she felt when she explored the museum before the concert started, rather than the concert having had a negative impact!

So what did the other participants say? Find out in our next post…