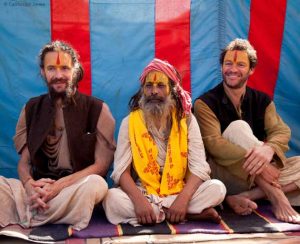

Dr James Mallinson is unique among British academics. Not only is he a widely-respected Sansrkit scholar at the School of Oriental and Africa Studies in London, he’s also the only Westerner ever to become a mahant – a senior sadhu [ascetic holy man] in a sect of yogis, which he has spent time with since he was 18. He’s recently co-authored (with Mark Singleton) a book called The Roots of Yoga, which is the first academic book to investigate the historical roots of yoga.I met him at the Jaipur Literature Festival and asked him about his journey.

Dr James Mallinson is unique among British academics. Not only is he a widely-respected Sansrkit scholar at the School of Oriental and Africa Studies in London, he’s also the only Westerner ever to become a mahant – a senior sadhu [ascetic holy man] in a sect of yogis, which he has spent time with since he was 18. He’s recently co-authored (with Mark Singleton) a book called The Roots of Yoga, which is the first academic book to investigate the historical roots of yoga.I met him at the Jaipur Literature Festival and asked him about his journey.

I watched the BBC documentary West Meets East, in which you and your friend the actor Dominic West went to the Kumbh Mela, the enormous gathering of sadhus that happens every three years. It was a fascinating insider look at that world – how 120 million people gather in one place and organize themselves, how the different sadhus distribute money to each other, and also the rivalry between different sects, which sometimes descends into fist-fights. Did that gang-war aspect of this huge spiritual gathering disillusion you?

I still find it hard to understand, but the sadhus don’t see it as a big deal. There’s a clear split between the yogis and the fighters. There was one incident, about 20 years ago, when my guru and another sadhu ended up fighting over me. I was lying back, having been drinking bhang [marijuana] all day, and it suddenly kicked off. It didn’t last very long, some other yogis jumped on the other guy, but some people asked me ‘why didn’t you jump in too?’ And my guru said, ‘he’s a scholar, he doesn’t fight’. I was quite relieved by that.

What have you got from your yoga practice over all these years?

A lot of it is just being part of this tradition, hanging out with the sadhus. As for the physical practices, I’ve only started practicing them more assiduously 10 years ago when I was working more as an academic and I started to get a stiff back. Since then I’ve become more religious, as it were, about doing it every day. I still sit down and meditate occasionally. It makes me feel good, happy, balanced. In this day and age, just sitting quietly and not reaching for your smartphone every minute is a good thing.

What do you like about the sadhu community in which you’ve spent so much time?

My guru never ceases to amaze me with his energy, his ability to be on it, despite hardly ever eating or sleeping, he’s always happy, never perturbed. As for the wider community, although they’re joyful and happy, deep down they see the material world as pointless. They don’t want to be a part of the world outside their religious round, their whole lives are predicated on being dissociated from it.

Do you find that detachment refreshing?

Yes. It’s got to be good for one’s mental level of happiness to completely experience a totally different way of life. You can go back to your life [working as an academic and living with his wife and two children in the UK]and realize some of the things you get wrapped up in aren’t that important.

Do you think your attraction to that world was partly a rejection of your background, growing up in England and going to a stuffy boarding-school?

It might have helped – I found myself once again in an all-male community governed by arcane rules.

Do you feel there is a lack of spiritual options in the West today, like the option to be a complete renunciate and for that to be an accepted social choice?

Yes I do. Just the other day I was speaking to a rather annoying young sadhu who was desperate for me to take him back to the UK so he could get followers. My guru has no interest in that, because he knows people just wouldn’t understand the life of renunciation. I suppose one option is to go and live in a monastery, but that’s not the same enjoyable, colourful life as at the Kumbh Mela.

But of course a lot of Indian gurus have gone to the West and become rock-star gurus. What do you think of them?

It doesn’t really rock my boat. The sadhus in the tradition I belong to explicitly shun that behavior. Some do public teachings, but I was told that if they’d done that 30 or 40 years ago they’d have been beaten up. Because it’s meant to be complete renunciation. The irony is, the more you renunciate, the more people give you material possessions. But the sadhus never build up a big storehouse of wealth, they tend to give it away. So those rock-star gurus like Osho, who accrued 95 Rolls Royces, that’s a different world.

But sadly those gurus who want to become rock-stars tend to be the most visible and famous. I suppose they’re not part of a tradition – they’re freelance gurus, with no one to answer to.

Those big-shots think they should get a big tent at the Kumbh Mela. But they can’t get a good spot, they have to camp out right at the outskirts, unless they pay a lot of money. They’re not respected by sadhus. Quite the opposite. My own guru couldn’t care less about publicity. I showed him the BBC documentary we made about my initiation at the Kumbh Mela, and after two minutes he stopped watching. He wasn’t interested at all, which is the perfect response.

What does a day at the Kumbh Mela look like in your community of sadhus?

You get up in the morning, do your ablutions, bathe – there’s a lot of bathing – then sit down and maybe start smoking, drinking chai. The ultimate behavior for a sadhu is to sit around and chat for hours and hours. Talking, chatting, gossiping, telling stories. There’s not much philosophical discussion.

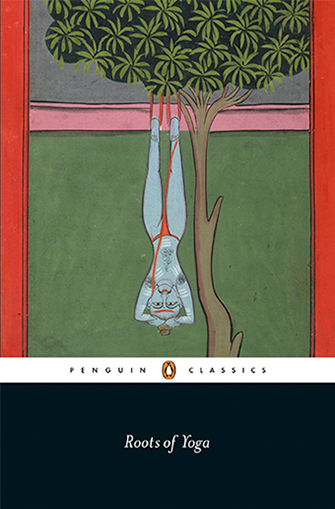

Tell me about the new book, The Roots of Yoga.

Tell me about the new book, The Roots of Yoga.

It’s a relief it’s over. It was five years hard work, involving the translation of over 100 texts, in 12 different languages. It’s the book I wish existed when I started exploring yoga. Nothing like it previously existed. A few books would have translations of a handful of texts but they wouldn’t be dated correctly and there was no understanding of how texts related to each other.

How does it change our understanding of the historical roots of yoga?

The conventional history is that yoga begins with Patanjali in the fourth century CE. That’s what most practitioners of modern yoga learn. My co-author Mark Singleton has written about how 95% of modern yoga is not from that. Much of it is more recent – many popular modern postures, like the sun salute, are only around 100 years old, and grew out of a number of influences, including Swedish gymnastics. In Patanjali, there’s almost nothing on physical postures, and it’s mainly 12 sitting postures to prepare you for meditation and breathing exercises. And there’s stuff on yoga earlier than that – Buddhist texts, Jain texts, some writing in the Mahabharata which has been almost entirely ignored, and some writing in the Upanishads. Yoga was practiced in a wide range of traditions with many different viewpoints. They all agree that ‘yoga works’.

But what does that mean, ‘work’? That it makes you healthy, or brings longevity, or grants enlightenment, or magical powers?

There are different interpretations, including of the word yoga or yuj itself. It can mean to concentrate or to unite. There’s a passage I often quote from one ancient text, which says, ‘whether you are a brahman, an ascetic, a Buddhist, a Jain, or even an atheist, if you practice yoga assiduously, it will work, you will attain siddhi’ – that can be translated as success or magical powers.

What do you think of the huge popularity of yoga in the West, and increasingly in India?

From a mercenary level it’s good for me. It means it’s easier for me to get funding. It’s nice to have a wider audience for your work. Is it a good thing in general? I think it probably is. One valid criticism is that it’s quite selfish. People do it for personal reasons. But even there, it’s beginning to mature. In the US, there are people trying to bring more social awareness back into yoga. People are also becoming more critically aware, they won’t accept from their guru that the asanas they practice are 5000 years old.

But that critical awareness hasn’t undermined your enthusiasm for the practice itself?

No – I’ve come across practices from the past that I try out. And I still begin with the sun salutation, even though I know it’s a modern innovation. It still feels good.

Finally, yoga is obviously being promoted by the Indian government, which has some ties to Hindu nationalism. Has it been at all controversial for you to decide that the earliest written texts on yoga are actually Buddhist?

No one’s noticed. We were nervous. But I don’t think they’re that interested in our scholarship.

This has been reposted from Jules Evans’ website Philosophy For Life