Anna Dowrick is a doctoral researcher at Queen Mary University of London in the Centre for Primary Care and Public Health. Her research is interdisciplinary, using anthropology, sociology, science and technology studies, gender and feminist studies, and health services research to explore the work of improving the care of victims of abuse by health professionals. Before undertaking her PhD she developed UK health policy on a range of issues, including dementia and cancer.

Anna Dowrick is a doctoral researcher at Queen Mary University of London in the Centre for Primary Care and Public Health. Her research is interdisciplinary, using anthropology, sociology, science and technology studies, gender and feminist studies, and health services research to explore the work of improving the care of victims of abuse by health professionals. Before undertaking her PhD she developed UK health policy on a range of issues, including dementia and cancer.

We’re sitting in Joanne’s consulting room. A tall cheese plant (officially a ‘monstera deliciosa’ she informs me) sits on her desk next to a picture of two young children, taking attention away from the computer, papers, charts, and other medical paraphernalia that share the space.

Joanne is a GP in a north London practice, She’s been qualified for about 10 years. We’ve met to discuss her experiences of providing care to patients who have been victims of domestic abuse. This is part of a wider project exploring the implementation of a programme called IRIS, which aims to increase referrals between general practice and domestic violence support services.

Joanne was shocked to discover the prevalence of domestic abuse. 1 in 4 women in the UK are expected to experience a form of abuse across their lifetime. She’d learnt this during the training she’d received the previous year, offered as part of the new IRIS domestic violence service. As part of this service, specialist domestic violence workers train primary care staff and offer them a referral pathway into support for their patients.

Before the training, she hadn’t realised what a big problem it was, or that the prevalence in general practice is even higher than the general population (1 in 3). Many people experience physical and mental health problems as a result of abuse which bring them to their GP. Depression, anxiety, chronic pain, IBS, headaches, tiredness. All things she saw regularly.

Health services, particularly general practitioners, have been positioned as important for improving the care of people affected by abuse by UK and international health organisations. The GP is considered a trusted figure and the practice a safe, accessible space to. A doctor’s visit can be the only opportunity someone has to be alone with a professional who could help.

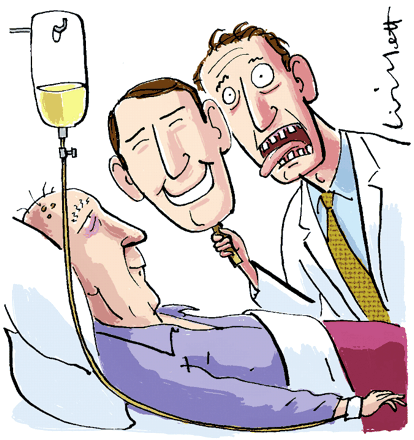

My research explores the emotional labour that GPs do to as part of their job to present an appropriate emotional front to their patients. While emotionally investing in patients is seen to be a core part of nursing and allied health professions, the historic Cartesian split between reason and emotion rests strongly on the side of reason for doctors. Good care is presented as a careful balance of empathy and objectivity.

Joanne doesn’t do this work because national guidance tells her to. She sees addressing domestic abuse as part and parcel of being a good GP. She differentiated herself from other GPs who were more ‘mechanistic’ and didn’t try and see patients as people.

Addressing domestic abuse didn’t feel different from the rest of her work. She sometimes worried about asking about abuse, appreciating that it was a stigmatised issue, but described feeling the same when discussing sexual health, drug and alcohol use, lifestyle choices. Being a GP was about creating a context to ask difficult questions.

In asking, she didn’t know what she might hear. Over her years as a practitioner she had become accustomed to her consulting room becoming a place of sanctuary, where tears could fall without judgement. Sometimes her patients’ stories affected her more than others, but she felt a professional responsibility to maintain emotional composure. It was after her surgery was finished that she might feel those emotions, often deciding to walk home rather than take the bus.

Though domestic violence was something that she felt a particular moral objection to, and would stir up feelings of sorrow, anger and frustration, knowing that she had a service she could offer to her patients made her feel better. Similarly to how her patients would describe disclosing abuse as taking a weight from their shoulders, she felt that having a referral pathway offered a way to share her own burden. She cautiously admitted that before the IRIS service she rarely asked about abuse because. She had been anxious about what she would be able to do about it.

She joked that her patients rarely did what she expected, and felt it was her responsibility to empower them to make their own choices. However, she saw a distinction between negotiating someone’s management of their diabetes, for example, and witnessing ongoing suffering resulting from domestic abuse. She felt domestic violence to be an injustice, an affront to her values. She had to draw a line between the things she could fix as a doctor and the things she couldn’t, and sometimes this recognition was painful. She felt fortunate to have a team that was supportive, with colleagues she could discuss complex cases with and acknowledged that not all doctors were so lucky.

Others of the 14 GPs I interviewed for this study offered a similar narrative. Caring for patients in abusive relationships fit neatly with what they understood about being a ‘good GP’. The things that were difficult about it – asking personal questions, offering a empathetic but practical response, maintaining confidentiality, providing consistent ongoing care, bearing witness to their suffering – were also satisfying parts of medical professionalism. The challenge was having the emotional energy to invest in this work in the face of growing pressure on their time and a fragmented service environment.

In 1967, John Berger reflected on the work of his good friend and GP John Sassall:

What is the effect of facing, trying to understand, hoping to overcome the extreme anguish of other persons five or six times a week? I do not speak now of physical anguish, for that can usually be relieved in a matter of minutes. I speak of the anguish of dying, of loss, of fear, of loneliness, of being desperately beside oneself, of the sense of futility.

John Berger (1967) A Fortunate Man: The Story of a Country Doctor

National and international policy-makers demand that GPs take a more central role in the response to domestic abuse. If we want them to face, understand and hope to overcome the extreme anguish of abuse, recognition of the emotional labour that this requires, and the support professionals themselves need, is vital. IRIS, as a service that shares the burden of care, is one step towards this but many more need to be taken.