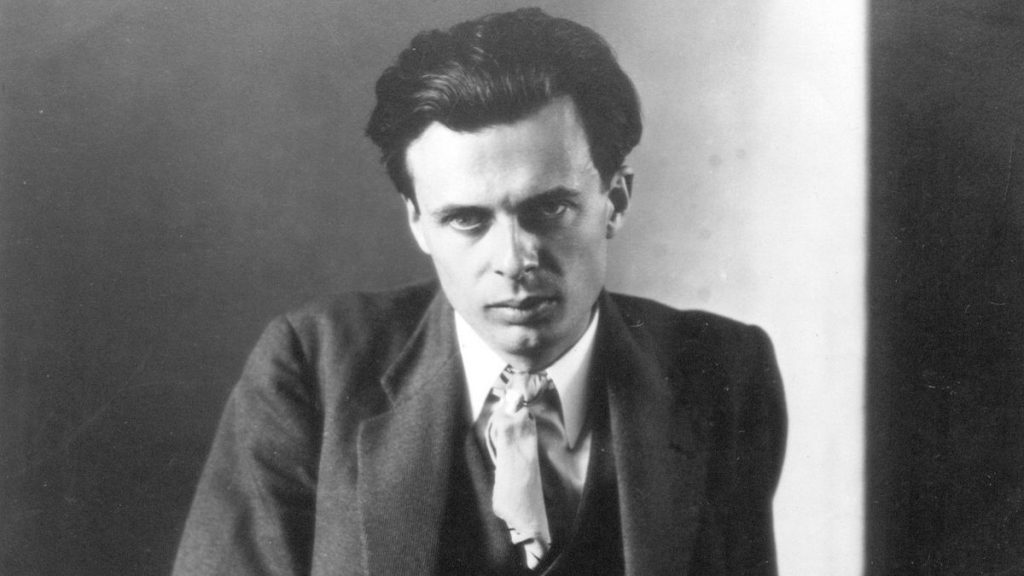

I’m researching a book about Aldous Huxley and his friends Alan Watts, Christopher Isherwood and Gerald Heard, and how these four posh Brits moved to California and helped to invent the modern culture of ‘spiritual but not religious’.

I’m researching a book about Aldous Huxley and his friends Alan Watts, Christopher Isherwood and Gerald Heard, and how these four posh Brits moved to California and helped to invent the modern culture of ‘spiritual but not religious’.

Of the four, Huxley is my favourite. My last book, The Art of Losing Control, owes him a profound debt. Writing a biography of someone is a bit like moving in with them – you start to notice all their annoying habits. Huxley definitely has some but, having now read pretty much everything he’s written, I can still say he’s a truly great thinker.

I think his greatest claim to fame is his analysis of humans’ urge to self-transcendence. I’ve read a lot of people on this topic – William James, Ken Wilber, Emile Durkheim, the great mystics. Huxley is the greatest analyst I know of this central domain of human experience.

He took from William James and his friend FWH Myers the idea that the conscious ego is just an island on top of a much larger ocean of human personality. There is also a ‘subliminal self’ which we carry around with us, which occasionally intervenes into our awareness. There’s all kinds of junk down there but – as Myers was the first to claim – there are also latent powers of healing and inspiration. At the deepest level, Myers suggested (and James and Huxley agreed), the not-self of the subliminal mind merges into the Atman, super-consciousness, Mind-at-large.

Huxley insisted – decades before Abraham Maslow – that humans have a ‘basic drive to self-transcendence’. We exist in our small, conditioned, utilitarian egos, cut off from our deeper selves, but it’s boring and claustrophobic in there, and we long for a holiday. Maybe the soul in us yearns to get out of the cocoon and unfold our wings.

Huxley’s genius was to appreciate all the different ways humans seek these holidays from the self: alcohol, drugs, dancing, art, reading, hobbies, sex, crowds, rallies, war. Having tried to cover this enormous terrain myself, I can tell you that no one else comes close in terms of having a bird’s eye view of the landscape. James, for example, only analysed ‘religious experiences’, which he defines as man’s solitary encounters with the divine. This is just a tiny corner of the field that Huxley covers – it doesn’t even take account of collective religious experiences, let alone all the transcendent experiences that humans have which don’t explicitly involve God.

Huxley also brought an acute historical analysis to the topic. He was an early pioneer of the history of the emotions, and the history of medicine – I could make a case that he actually invents the history of the emotions, with his essay on accidie in 1923 * . He suggested that, while humans have basic drives, such as the drive to self-transcendence, those drives take different forms depending on a person’s temperament, physique and culture.

He argued – and this was one of the principal themes of my book The Art of Losing Control – that mystical transcendence had been marginalized and pathologized in western culture, starting from around the Reformation. It became embarrassing and ridiculous to admit to the sorts of mystical experiences which were highly valued in medieval culture. ‘We keep them to ourselves for fear of being sent to the psychoanalyst’, he said.

Lacking in role models or institutions for genuine mystical transcendence, western culture instead offers us what Huxley called ‘ersatz spirituality’ – package holidays from the self, such as consumerism, gadget-idolatry, booze, casual sex, and nationalism, which Huxley thought was the dominant religion of the 19th and 20th centuries (it’s returned with a vengeance in the 21st century).

What’s the solution? Rather than preaching a return to Christian orthodoxy, as TS Eliot, WH Auden or CS Lewis did, Huxley beat out a new path, which has proved much more influential in western culture: learn spiritual practices from the world’s religious traditions, test them out using empirical psychology, and find the ones that work for you.

He outlined this approach in his 1946 anthology, The Perennial Philosophy. I’ve loved this book since I was a teenager (I still have the copy I stole from the school library). It first introduced me to the likes of Rumi, Traherne, Chuang Tzu, Hakuin and Meister Eckhart, and helped me realize how much the world’s wisdom traditions share. But now I can see its flaws.

This was a book born out of historical despair. Huxley had played a central role in the British anti-war movement, and then abruptly abandoned it in 1937 to move to the US, ending up living with his wife in a hut in the Mojave desert. He thought western civilization was heading for destruction, and that literally our only hope was for a handful of people to dedicate themselves to mysticism at the margins of the general awfulness, like the Essenes seeking gnosis in the desert.

The only hope was if the Perennial Philosophy became generally recognized and embraced by humanity. He insisted the world’s great mystics all agreed on all the core points. But this was an argument born more of political despair than calm scholarship. It over-emphasized the extent to which mystics of different traditions agreed. And it ended up ranking mystical experience – only emotionless encounters with a formless, imageless divine are ‘true mysticism’, while any encounters with the divine in a particular form are considered second-rate.

You can understand how this is important to Huxley’s political dreams (humans fight over particular forms of the divine, so it’s better if we all meet in the Clear Light). But it’s pretty outrageous for him, a new convert to mysticism with hardly any practical experience, to lay down the law as to what is or isn’t a genuine encounter with the divine. How the hell does he know?

You can understand how this is important to Huxley’s political dreams (humans fight over particular forms of the divine, so it’s better if we all meet in the Clear Light). But it’s pretty outrageous for him, a new convert to mysticism with hardly any practical experience, to lay down the law as to what is or isn’t a genuine encounter with the divine. How the hell does he know?

There’s an obvious anti-Abrahamic and pro-Hindu/Buddhist bias in his vision. He hates any religions that are time-based (ie with a historical vision), and thinks Buddhism and Hinduism are more tolerant because they’re more focused on the ‘eternal now’. Odd to argue for Hindu tolerance at the precise moment millions of Hindus and Muslims were massacring each other during the Partition.

But in more practical terms, it’s a very lonely, intellectual and bookish sort of spirituality that he offers (that must be why it appealed to me). There’s no mention of the role of community, or elders, or collective rituals. Just the intellectual and his books in the desert. ‘These fragments I have shored against my ruins’.

And it’s a hard path. Huxley, in effect, says that the only possible route for humanity is straight up a sheer cliff face. Anyone can be a mystic, he says. You just need to be completely detached from all worldly things and totally focused on the divine. No biggie.

It turned out to be very difficult. He suffered several hard years of failure and self-disgust, during which he wrote Ape and Essence, his most horrible and despairing book. He admitted at the end of his life that he’d never had a mystical experience. God will not be rushed.

But by the 1950s, he’d relaxed, and moved into his mature spirituality. Rather than insisting on the sheer cliff face of ascetic mysticism as the only route to salvation, Huxley accepted there were lots of practices one could do here in this world to make yourself healthier and happier on your long, multi-life journey to enlightenment.

He understood more and more the importance of the body to well-being and realization, and was an early supporter of gestalt therapy, the Alexander technique and hatha yoga. He finally found a place for sex in his spirituality – Island includes elements of Tantric practice. He also found a new appreciation for ecstatic dance – notice the children in his utopia, Island, practice ecstatic dance to ease themselves of anxiety. This was a decade before Gabrielle Roth developed 5Rhythms at Esalen. It’s a pity we never got to hear his thoughts on Beatlemania – they were certainly into him, and put him on the cover of Sgt Pepper’s.

He was also a big fan of hypnosis, and taught himself to be a hypnotist (his friend Igor Stravinsky claimed Huxley was a healer, and had cured him of insomnia). And, of course, he discovered that psychedelics offered a short-cut to temporary ego-dissolution. Those were the only times he ever really got a glimpse of the divine – when he was high.

It was tremendously shocking that this great English man of letters should preach the chemical path to liberation. But Huxley quite rightly pointed out that humans have been using psycho-active plants for religious rituals for several millennia. Other spiritual exercises rely on alterations in body chemistry, such as chanting, fasting or flagellation. That an alteration in body-chemistry is the means to a spiritual experience doesn’t mean that experience is only bio-chemical.

In the last decade of his life, the disgusted prophet of the desert became an unlikely hit on American campuses, lecturing to thousands of students at a time on visionary experience and integral education. This is his second great claim-to-fame. He had a vision that universities could offer an integral education which avoided over-specialization and over-intellectualization, and which instead educated the whole person – their body, their subliminal mind, their intellect, their social and political self, their relationship to nature, and their higher consciousness.

That vision of education proved hugely popular with baby-boomers, and yet somehow – such is the inertia of the university system – it’s had very little impact on what universities offer in the sixty years since then. They still offer the same over-specialized and totally intellectual learning experiences to undergrads, alas. His vision was, however, a defining influence on alternative colleges like Esalen, the Garrison Institute, CIIS and Schumacher College.

Today, we are all Huxley’s children. The ‘spiritual but not religious’ demographic is the fastest growing in the US. Contemplation has enjoyed its biggest revival since the Reformation. We are all influenced by ‘empirical spirituality’ like the science of mindfulness. Most westerners say they’ve had a mystical experience. And the psychedelic renaissance that Huxley called for 60 years ago may finally be happening.

* As to Huxley inventing the history of the emotions – his 1923 essay on accidie was decades before Lucien Febvre’s 1941 article calling for a history of emotions. He also wrote a ‘History of Some Fashions in Love‘ in 1924. Huxley argued in Ends and Means (1937) that humans’ basic drives take different forms or ‘canals’ during different eras in history. His historical novel Grey Eminence (1941) analysed the history of western meditation, and drew heavily on Bremond’s Literary History of Religious Sentiments in France, which was a principle inspiration for Febvre as well – so it’s interesting to ponder whether Grey Eminence was a direct influence on Febvre’s idea. We know at least it was read and reviewed in the 1945 edition of Annals of Social History, which Febvre edited. Febvre and Huxley’s brother Julian later fell out over UNESCO’s grand ‘history of humanity’ project, but that’s another story.

But it’s Huxley’s Devils of Loudun (1952) which to my mind is Huxley’s greatest work of history of the emotions. It’s fascinating in its historical analysis of possessions, witchcraft, and how changing attitudes altered how people perceived and experienced ecstatic phenomena. He notes, for example, that by the Victorian era possession by demons has more or less disappeared, while possession by dead souls became more common. And he notes that by the 20th century, people have started to report being possessed by machines, particularly radios. Devils also has an extraordinary footnote on the clystère or enema-pump as a medical procedure for melancholy and exorcisms, and how it entered the West’s pornographic imagination as a result. You can see it in the bottom-right of Durer’s famous engraving Melancholia, below. He also mentions a painting of a clystere procedure by Boucher, although I haven’t been able to identify this.

Later in his career, Huxley wrote essays on the history of tension, and on the history of visionary experience and artistic culture (that essay, later published as Heaven and Hell, is unsurpassed as an analysis of the arts and ecstatic experience). He was uniquely well-placed to develop this sort of interdisciplinary endeavour, and was an early pioneer of the medical humanities, popping up to give historical and philosophical speeches at medical conferences in the 1950s and 1960s (his speech on the history of tension was given at a conference on tranquiizers). His ability to act as a ‘pontifex’ or bridge-builder between the sciences and humanities had a profound influence on psychedelic science – thanks to him, early researchers like Humphrey Osmond and Timothy Leary came to interpret psychedelics through the lens of mystical experience.

Did Aldous Huxley invent the history of emotions? Many more traditional historians could lay a claim as well – Huizinga, Elias, Febvre, Norman Cohn. But Huxley deserves to be mentioned in the history of the history of emotions as well.

Durer’s Melancholia, with the clystere in the bottom right corner