Will Watson is a PhD candidate at the School of History, Queen Mary University of London. In this post for the History of Emotions Blog, he reflects on the place of anger in the civil rights movement in Northern Ireland in the 1960s and 1970s, and asks what a history-of-emotions approach can add to our understanding, with particular reference to Barbara Rosenwein’s recent book about anger.

Will Watson is a PhD candidate at the School of History, Queen Mary University of London. In this post for the History of Emotions Blog, he reflects on the place of anger in the civil rights movement in Northern Ireland in the 1960s and 1970s, and asks what a history-of-emotions approach can add to our understanding, with particular reference to Barbara Rosenwein’s recent book about anger.

This is the latest in a series of research posts, conversations, and reviews asking ‘What is anger?’

As Rob Boddice argues:

at the heart of the history of emotions… …is the claim that emotions have a history. They are not merely the irrational gloss on an otherwise long narrative of history unfolding according to rational thought and rational decision-making. Nor are emotions merely the effect of history; they also have a significant place, bundled with reason and sensation, in the making of history.[1]

What this suggests is that there is a need to acknowledge the role that emotions play throughout history; that is, emotions hold the key to a deeper and important layer to better understanding individuals, actions, communities, cultures, and societies of the past. Building upon such observations, my PhD, entitled ‘The Emotions of The Civil Rights Movement in Northern Ireland, 1963-1972’ explores how emotions played an important role in influencing the motivations, goals, ideology, strategy formation and mobilization of individuals and organisations involved within this social movement.

My work seeks to understand, for example, what emotions were in play at any given moment, what frameworks emotions were understood in and how they then led to, and shaped, the emergence of the Civil Rights Movement (CRM) and political discourse and activities, such as street politics, protest, and civil disobedience. Although my research explores other emotions, such as shame, guilt and humiliation, anger was a key emotion felt by those who participated within the CRM. From the anger of Catholics over issues of discrimination, such as perceived bias in housing allocation, to anger felt due to perceptions of poor Nationalist political representation, anger was an underlying emotion that influenced both individual and collective action. This raises the question of how one might explore and understand such an emotion within a historical framework.

Although research within both psychology and neuroscience suggest that anger occurs naturally – originating in the amygdala in response to internal or external stimuli, for example – studies have also shown that anger can be nurtured: anger and resulting behaviours and expression can be learned, and influenced, through upbringing, relationships, culture, and society. This allows for anger to have a history, as it implies that anger has both social and cultural specificity. Therefore, when historical actors speak of their emotions, such as anger, historians must seek to contextualise it within a cultural and social framework.

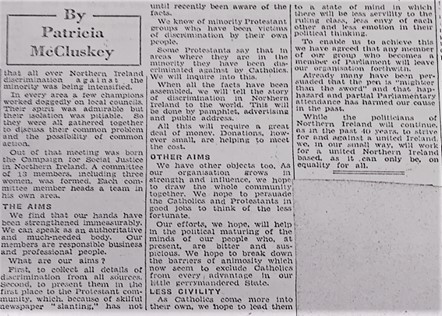

To illustrate this, my own research can offer an example. Conn McCluskey, a founding member of the Campaign for Social Justice (CSJ) – an organisation that sought to end discrimination in Northern Ireland through constitutional means – believed that anger should be rejected; this was influenced, in part, by his religious beliefs. He acknowledged that he felt angry but perceived it as sinful and a gateway emotion to sectarian violence, as it would perpetuate Protestant Loyalism and Catholic Republicanism. Therefore, when forming a strategy to challenge discrimination, he opted for a non-aggressive approach – one that was solely based on statistics and reason. What can be seen is that his understanding of anger, and the anger of others, was influenced by religion, culture, and society – set within his historical context; this, in turn, had an impact upon how he chose to express anger, and, therefore, upon the history of the CRM.

Article published by the Irish News, 1964, by Conn McCluskey’s wife, Patricia, stating the aims the of Campaign for Social Justice. Picture source: Irish News,1964, D2293/1, Dungannon Affair Files, Box 1, Folder 2, Public Record Office Northern Ireland.

The idea that anger has a history is not a new concept within the history of emotions, yet the approach to better understanding it within a historical framework remains debated. It is here that a new book by Barbara Rosenwein (previously reviewed for this blog by Imke Rajamani) can offer further insights. By arguing for the historically changing and culturally defined nature of anger, Rosenwein’s book continues to challenge the idea that emotions are hardwired and serves as an example of how one might think of anger as nurtured and contextually influenced. To better understand earlier forms of anger, Rosenwein again offers her concept of ‘emotional communities’: homes, schools, businesses, tribes, for example, that share norms and values with regards to emotions and emotional behaviour. As she states: ‘each community favours some emotions and shuns others; each expresses its emotions in characteristic ways’.[2]

Although my own research does not utilise Rosenwein’s ‘emotional communities’ framework specifically, that approach does provide important methodological and theoretical considerations for my PhD, and for the study of the history of anger more generally. Rosenwein argues that the historian of emotions must uncover a system of feeling by looking for emotional commonalities and disparities within social and cultural context; to understand how emotions were understood both individually and collectively; to analyse which emotions were valued and which were deplored; and to analyse how such emotions were expressed, acted upon and with what consequences. Regardless of methodological and theoretical approach, such issues are fundamental to understanding anger in the past.

Rosenwein illustrates this in her book by studying different emotional communities. For example, Rosenwein first explores the concepts of Buddhism, Stoicism and Neo-Stoicism. Similarly, amongst these emotional communities, anger was believed to be a disadvantage and something to be abandoned or rejected. Each community shared a view of anger as having a deleterious impact upon individuals, but the understanding of anger and the approach to removing it varied. The Buddha proffered anger as suffering and a matter of ego that needed to be transcended. Conversely, Seneca, the most widely read of the Roman Stoics, argued that anger was part of human nature – it could not be avoided but could, through practice, be minimised and controlled.

In the second section of her book, Rosenwein explores anger as a vice and/or virtue. Here she analyses, for example, Aristotle and Pope Gregory the Great and, generally, the history of Christian understandings of anger. This view of anger was far removed from the anger of the Buddha or Seneca but is more closely related to the ‘righteous anger’ of the Patristic era Christians, right through to what emotional communities in a contemporary, modern society might believe. Finally, Rosenwein considers ‘natural anger’, analysing early medical understandings of anger, where emotional communities such as those that centred around the teachings of Galen and, later, medieval humoral theory, saw anger as a naturally occurring part of human nature, and, therefore, an unavoidable part of human existence.

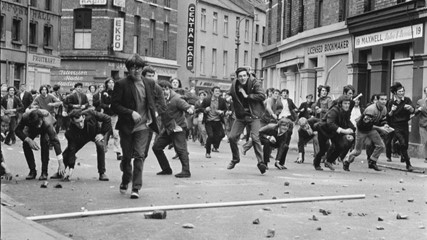

Young people in Londonderry throwing bricks at the Royal Ulster Constabulary, c.1969, Source – BBC article: In Pictures: Derry in 1969

What Rosenwein’s examples demonstrate is that what might be seen simply as anger (or emotions, generally) – an outward expression or inner feeling – is, in fact, more complicated, often rooted in social conditioning and deeply held beliefs. It suggests that the communities that people are part of will determine their understanding and expression of anger, and even its functionality, and shows that even when individuals and the collective have shared values, or a shared ideology or religion, understandings of anger can be nuanced enough to define a community as uniquely separate from another.

This insight about the way that community rules and identities are fundamental to emotional life, is evident within my own research: where organisations, such as the CSJ, suggested that anger should be abandoned completely, others, particularly those that were young and more radical, saw the expression of anger as justified, and a necessary tool for mobilisation. Although both organisations had the same religious beliefs, the goal to end discrimination, and were part of the same movement – and, as Rosenwein would argue, part of a wider CRM emotional community – their differing view of anger and how it should be expressed separated them. This is an important consideration, particularly when trying to uncover the varying motivations, actions, and disparities within the CRM, and to understand why violence occurred during protest and marches.

Battle of the Bogside, Londonderry, 14 August 1969. Violence erupted when civil rights marchers were cordoned off by the Royal Ulster Constabulary and confronted by Unionist counterdemonstrators. Source – History Pod, 12th August 1969: The Battle of the Bogside

Although such an approach offers important considerations for understanding past anger, there are some further theoretical concepts worth mentioning. The ‘emotional community’, as a concept, does not address the importance of embodiment or spaces for understanding anger. Instead, it suggests that society, culture, communities, and the emotions within, are mentalised and, therefore, relatively static; that anger adheres to a strict system of norms and values. However, as contemporary research within history, sociology and psychology suggests, anger can be both cognitive and subject to spaces and bodily conditioning.[3]

The dual cognitive and bodily nature of anger was also something that has become evident in my own research. Although civil rights groups acknowledged some emotions to be important for encouraging action, the environments that protesters found themselves in often led to emotions that were beyond cognitive reasoning. Throughout the Civil Rights Movement, Catholic protesters were banned from entering certain areas, particularly areas that were heavily dominated by Unionists or areas that had significant emotional value to Loyalists. Many marches were cordoned off by the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and far-right Unionist/Loyalist organisations. Such occurrences led to spaces becoming latent with emotional meaning – both for areas that protesters were banned from entering and for the spaces that they were confined to. Naturally, such spaces, and what occurred within them, gave rise to emotions that were not reasoned. In addition, my research has discovered that many participants that attended protest marches had no intention of conducting themselves aggressively. On the contrary, many had reasoned that emotions such as anger would be harmful to their cause. However, the spaces and bodily connection within protests engendered emotions such anger, rage, shame, and pride, often in response to ritualistic behaviours (chanting and the singing of patriotic songs, for example) and in response to the perceived threat of counter demonstrators and the RUC.

To fully understand anger within a historical framework, then, I suggest that a middle-path should be followed, understanding historical actors both as autonomous, cognitive agents, and also as subject to the emotional power of spaces and embodiment. The former suggests that individuals of the past controlled and made conscious decisions regarding their anger, which had a significant impact upon their actions, expressions, and behaviours.[4] In line with Rosenwein’s approach, such appraisals can be influenced by religion, ideologies, culture, and society. Therefore, seeking to understand the various communities that people are part of, whether a civil rights movement or political organisation, remains a valuable empirical tool. The latter, however, requires uncovering individual and collective experiences, such as through spatial environments and ritualistic behaviours, and how these created bodily manifestations, sometimes separate from conscious or cognitive processes. This moves beyond the traditional method of discourse analysis and seeks to analyse accounts of observable behaviour, making use of third-person accounts as viable sources to uncover emotions of the past – particularly anger.

References

Boddice, Rob. “The history of emotions: Past, present, future.” Revista de Estudios Sociales 62 (2017): 10-15.

Gammerl, Benno. “Emotional styles–concepts and challenges.” Rethinking History 16, no. 2 (2012): 161-175

Gammerl, Benno. Jan Hutta, and Monique Scheer. “Feeling differently. Approaches and their politics.” Emotion, Space and Society 25 (2017): 87-94.

Pernau, Margit, (2014). Space and emotion: building to feel. History Compass, 12(7), 541-549

Rosenwein, Barbara H. Anger: The conflicted history of an emotion. Yale University Press, 2020

Rosenwein, Barbara H., ed. Anger’s past: the social uses of an emotion in the Middle Ages. Cornell University Press, 1998.

Rosenwein, Barbara H. Emotional communities in the early middle ages. Cornell University Press, 2006.

Rosenwein, Barbara H. “Problems and Methods in the History of Emotions.” Passions in context 1, no. 1 (2010): 1-32.

Scheer, Monique. “Are emotions a kind of practice (and is that what makes them have a history)? A Bourdieusian approach to understanding emotion.” History and theory 51, no. 2 (2012): 193-220

[1] Rob Boddice, “The history of emotions: Past, present, future.” Revista de Estudios Sociales 62 (2017): 10-15, 11.

[2] Barbara H. Rosenwein, Anger: The conflicted history of an emotion. Yale University Press, 2020, 4; see also Barbara H. Rosenwein, “Problems and Methods in the History of Emotions.” Passions in context 1, no. 1 (2010): 1-32; see also Barbara H. Rosenwein, ed. Anger’s past: the social uses of an emotion in the Middle Ages. Cornell University Press, 1998; and Barbara H. Rosenwein, Emotional communities in the early middle ages. Cornell University Press, 2006.

[3] See, for example, Monique Scheer, “Are emotions a kind of practice (and is that what makes them have a history)? A Bourdieuian approach to understanding emotion.” History and theory 51, no. 2 (2012): 193-220; and, Margit Pernau, (2014). Space and emotion: building to feel. History Compass, 12 (7), 541-549.

[4] Benno Gammerl, “Emotional styles–concepts and challenges.” Rethinking History 16, no. 2 (2012): 161-175; and Benno Gammerl, Jan Hutta, and Monique Scheer. “Feeling differently. Approaches and their politics.” Emotion, Space and Society 25 (2017): 87-94.