Harriet Canty took the History of Emotions undergraduate module at Queen Mary University of London during 2020-21.

Harriet Canty took the History of Emotions undergraduate module at Queen Mary University of London during 2020-21.

In this post, one in a series of contributions by QMUL students to the History of Emotions blog, Harriet enters the historical world of duels, hurt feelings, and defamation to ask whether people are feeling more offended now than ever before.

In 2017 the BBC recorded a podcast, Offence, Power and Progress presented by journalist Mobeen Azhar which grapples with the notion of feeling offended in a modern context and the wider political repercussions of this reaction. The accompanying article to this programme posed the question “are we more easily offended than ever before?”. References to the “snowflake generation” or over-sensitive “woke” millennials, if only in the depths of Piers Morgan’s Twitter, reinforce this idea of being “easily offended” as a relatively new phenomenon, tied to a specific generation. Along with the notion of a lost sense of humour and a longing for a time where freedom of speech wasn’t so heavily policed and cancel-culture non-existent; “offended” has come to feel like a buzzword for our times. Yet, by placing the notion of feeling offended within a historical and cultural context, can we understand its status in modern day society?

I understand “offended” to mean “to be displeased, vexed, or annoyed”, coming from late twelfth century Old French. Yet, a search on the Oxford English Dictionary Online spells out the complex etymology of the word with definitions such as “striking one’s foot” or being “tempted into sin” now being out of use, along with the idea of “committing a crime” which still stands today. Whilst these descriptions seem quite different from my original understanding of feeling offended there is some overlap with the idea of inflicting pain or acting immorally. The numerous emotions that come into our current understanding of the notion of offence include “outrage” and “hurt” but as we look back historically “anger” and “humiliation” seem to be more relevant.

The duels of the eighteenth century saw the elite battle for the sake of their honour and their status both of which entitled them to respectful treatment, as we recently learnt from Netflix’s Bridgerton. Those who swallowed insults were seen to not respect themselves enough. Though these duels tended to be between gentlemen, of equal standing, it is a duel between two ladies, colloquially known as petticoat duels, which stood out most to me. In 1792, Mrs Elphinstone insinuated that Lady Almeria Braddock was much older than she claimed to be. This offensive comment led to a duel. There is some contention as to whether this truly took place but supposedly once Lady Almeria had managed to inflict a wound on her opponent’s sword arm both women were satisfied. Whilst risking one’s life for the sake of a mildly offensive comment seems much more extreme than our modern day equivalent of taking to Twitter, a key similarity seems to be a demand for respect. Another interesting distinction is the sense that gaining satisfaction in a duel seems to end all tension between parties, something that given today’s supposed cancel culture we seem to lack.

Taking offence didn’t have to be quite so extreme, shown through Laura Gowing’s analysis of Early Modern defamation cases. The number of these cases rose substantially in the 1600s with over two-hundred cases per year by the 1620s, three quarters of which were taken forward by women. Whilst men would face allegations of drunkenness or debt, women tended to face sexual defamations which called into question their virtue, showing how feeling offended overlaps with ideas of embarrassment or humiliation. A study in 2018 by the Roma Tre University sees the emotional state of “feeling offended” as affected by personal factors including gender. While women tended to express sadness and bitterness when offended, men acted in anger and pride. Whilst there have been shifts to varying emotional states within feeling offended throughout history many of them relate to our current understanding of the word.

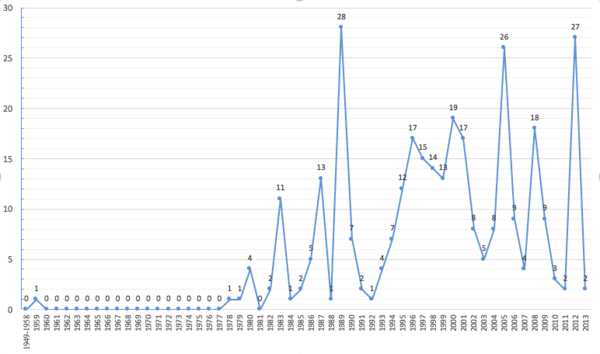

The examples so far have shown how individuals have taken offence from words or actions that caused damage to their honour or reputation. Though offence can take this form today it is also often felt on behalf of a group that the person may either be a member of or an ally to, whether that’s LGBTQ+ or BAME. However, this idea of collective offence is better illustrated by looking at China. In 1959 the Chinese Communist Party’s newspaper, the People’s Daily, used the phrase “hurting the feelings of the Chinese people” (伤害了中国人民的感情). The graph above tracks the usage of this phrase over following decades showing the increase in its popularity in the 1970s when the phrase became a feature of the Party’s political discourse. In 2007 China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that Saint Lucia had “hurt the feelings of the Chinese people” by allowing a visit from the “so-called ‘foreign minister’” from Taiwan. Here, if we take “hurt feelings” to be an offshoot of feeling offended, the collective nature of China’s offence may well be reflective of the highly collectivist Chinese culture as opposed to the West’s individualistic ideology. These cultural differences are key, from people taking offence for using your left hand in India to laughing with your mouth open in Japan. The notion of feeling offended varies by culture and time period showing that what we are offended by is by no means inherent in humans.

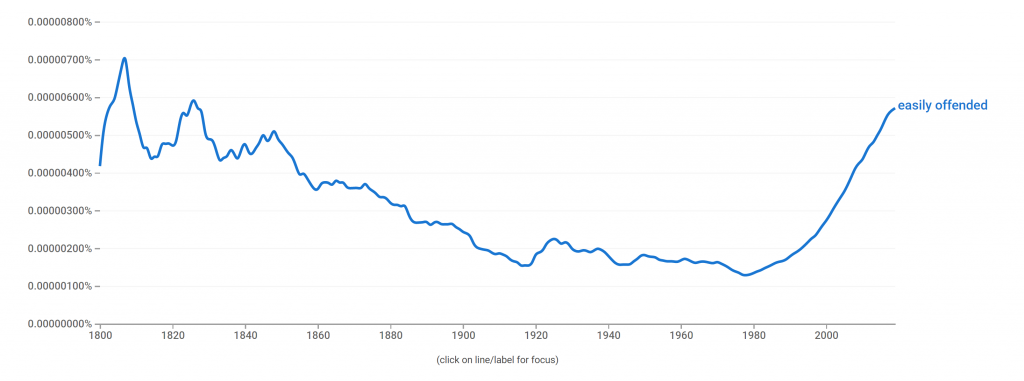

If we take a look at the Google Ngram for “easily offended” it suggests that those who see society as more offended than ever before may well be incorrect, perhaps the lull in the twentieth century has led to the assumption that there is no historical basis for taking offence. Whilst what has offended people has varied over the years the feelings surrounding offence and what is essentially a demand for respect, remains. Perhaps Twitter has somewhat evened the playing field allowing for not only the elites to voice their discontent and therefore projecting the voices of those who feel most disrespected. “Offended” has become a media buzzword for clickbait articles, occasionally enhanced with all capitals and often focusing on the latest Megan Markle drama, allowing for offence to be depicted as an irrational reaction. But “offended” is also used to describe more serious matters including xenophobia or racism and by using the term too freely we risk trivialising it. Irshad Manji, in a short video for Time Magazine, gives a nuanced understanding of feeling offended suggesting that there is much to be learnt from engaging with those who offend you and attempting to gain common ground. Perhaps by understanding the historical and cultural context of offence it validates its current position in modern day society as essentially a demand for respect.

Further reading:

Are we more easily offended than ever before?, BBC, November 2017

Robert Baldick, The duel: a history of duelling, London: Spring Books, 1970

David Bandurski, “A History of “Hurt Feelings”, China Media Project.

Mark Clifton, “What Duelling Can Teach Us About Taking Offence”, Aeon magazine, October 2018.

Jessica Goldstein, “The surprising history of ‘snowflake’ as a political insult”, Think Progress, January 2017

Laura Gowing. “Gender and the language of insult in early modern London”, History Workshop, no. 35, pp. 1-21, Oxford University Press, 1993

Isabella Poggi, and Francesca D’Errico. “Feeling offended: a blow to our image and our social relationships.” Frontiers in Psychology 8 (2018).