After the riots in England earlier this month, emotions and education have loomed large in resulting social commentaries. One chief constable, Chris Sims of the West Midlands police, said of the Birmingham rioters that they were “not an angry crowd, but a greedy crowd”. Whether the problem is supposed to be greed or anger, or indeed despair, selfishness, rage, envy, ennui, or mindless criminality, it would seem that emotions are at the heart of this new social disorder. And, for many, it is education that can provide the cure.

David Cameron says his renewed attempt to fix the “broken society” and to reverse the current “moral collapse” will involve improving education (in as-yet unspecified ways). The Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, speaking in the House of Lords, said that our national educational philosophy had become too “instrumentalist”and should be directed instead towards building “virtue, character and citizenship”. Williams, for one, wants to use the riots as an occasion to rethink the entire “content and ethos of our educational institutions.”

It is yet to be seen what specific initiatives will be proposed, but it is likely that they will relate, one way or another, to the idea that schools should be in the business of training the emotions as well as the intellect.

The aim to teach “emotional literacy” in schools came under the banner of ‘SEAL’ (Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning) under the previous UK government. We do not know exactly what will come next, but over the last couple of years, several of us at Queen Mary have been thinking about these issues in broader historical, artistic and educational contexts as part of a project entitled ‘Embodied Emotions’.

Working with a local primary school, we have combined classroom workshops with interdisciplinary academic seminars to investigate the whole area of emotional literacy and the primary school curriculum.

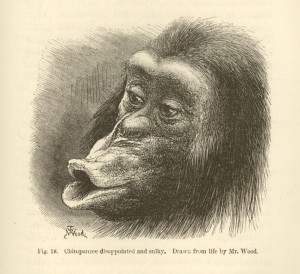

"Chimpanzee disappointed and sulky" from Charles Darwin, The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872)

I’ve written up a provisional report of one aspect of my historical work on the ‘Embodied Emotions’ project, which involved taking historical images (such as the “disappointed and sulky” chimp pictured) into the classroom as a way to stimulate discussion of feelings, emotions and expressions – with some quite intriguing results. The report, entitled ‘Feeling Differently’, links my experiences at Osmani School to wider scientific, educational and philosophical debates about expression, the emotions and the intellect.

This is just one of the historical aspects of the project – another will be an historical study of ideas about emotional education since the late 18th century, which I am still researching.

Download the ‘Feeling Differently’ Report

Thomas Dixon.

Pingback: Interactions - Creative Strategies for Business

Pingback: History of emotions news digest | The History of Emotions Blog

Pingback: The Many Faces of Emotion | The History of Emotions Blog