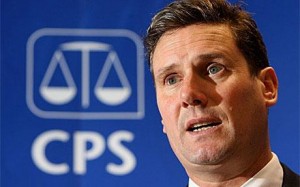

The Commission on Assisted Dying (COAD) published its report this month, recommending ‘providing the choice of assisted dying for terminally ill people.’ The report’s proposed changes focus specifically and exclusively upon ‘terminal illness’. David Cameron indicated prior to the report’s publication that he would resist changes in the law, already noted by Jules Evans on this blog. The present operation of the law was influenced by the success of Debbie Purdy’s campaign in 2010 to get the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) [Kier Starmer, pictured] to lay out the factors that might contribute to a prosecution for ‘assisted suicide’ being pursued ‘in the public interest’, and those in which the DPP would ‘exercise discretion’ and not prosecute, without changing the law. This situation is labelled ‘inadequate and incoherent’ by COAD. If legal incoherence is the key to reform, it is vital to understand the history of such a disorganised situation.

One of COAD’s key foci is the 1961 Suicide Act which decriminalised suicide in England and Wales. The report states that it is ‘almost universally accepted that there needed to be some change to the terms of the Suicide Act 1961’, specifically section 2(1) that created the offence of ‘assisted suicide’. Whilst suicide ceased to be a crime, the specific offence now referred to as ‘assisting suicide’ was created. The DPP’s oral evidence to COAD highlights the uniqueness of the legal position: ‘Under the 1961 Act there is obviously a broad offence of assisted suicide, it’s obviously peculiar because you’ve got aiding and abetting — using the old language — conduct which is not itself unlawful so you’re in very odd territory.’

Suicide was decriminalised in 1961 for a variety of reasons, including a broad concern about criminal law intervening in areas of ‘moral conduct’, and the unnecessary ‘distress’ caused to the family of the deceased by the taint of criminality. However, a key motivation behind the Act is revealed in a fractious exchange between Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and his reformist Home Secretary R.A. Butler. Macmillan grumbled, ‘[m]ust we really proceed with the Suicides [sic] Bill? I think we are opening ourselves to chaff if, after ten years of Tory Government, all we can do is to produce a bill allowing people to commit suicide. I don’t see the point of it.’ Butler countered that ‘[t]he main object of the Bill is not to allow people to commit suicide with impunity… It is to relieve people who unsuccessfully attempt suicide from being liable to criminal proceedings.’

These ‘unsuccessful attempters’ – for which the stereotype was women under 30 – were fast becoming an epidemic phenomenon in British hospitals. Erwin Stengel, an authority on the subject, related in 1959 that ‘the police officer may inform the doctors in hospital that… he will bring a [criminal] charge for the purpose of having the patient put on probation under the condition that he consents to hospital treatment’, whether the doctor thinks such treatment is appropriate or not. Stengel also lamented that many patients lie about having attempted suicide because they ‘are afraid that the doctor may report their offence to the police’ denying themselves ‘the possible benefit of psychiatric treatment which is impossible if the truth is withheld from the doctor.’

Thus the decriminalisation in the 1961 Act can be seen as part of a government strategy aiming to provide better care for people who had ‘attempted suicide’. However, it was noted that such changes could open unintended loopholes. The terms of reference for the Criminal Law Revision Committee set up by Butler to investigate the practicalities of the law change showed acute awareness of this:

‘[t]he abolition of the offence of suicide would involve consequential amendments of the criminal law to deal with offences which would cease to be murder if suicide ceased to be self-murder… on the assumption that it should continue to be an offence for a person (whether he is acting in pursuance of a genuine suicide pact or not) to incite or assist another to kill or attempt to kill himself, what consequential amendments in the criminal law would be required[?]’

This is achieved through clause 2(1) which created the offence of ‘aiding, abetting, counselling or procuring the suicide of another’. Concerns around the potential culpability of supposed ‘suicide pact’ survivors – which came to prominence around the Homicide Act (1957) – were key in the creation of the law now contested in very different circumstances by COAD.

A concern about the right (psychiatric) care of those who survived ‘suicide attempts’ led to the creation of an offence specifically to limit the knock-on effects of decriminalisation and to make this ‘retraction’ of the law relate as precisely as possible to ‘attempted suicide’. The offence corresponds to a debate far removed from the current one around ‘terminal illness’. The concern of section 2(1) about undue ‘influence’ when assisting suicide is one of the only current resonances even though, in 1961, it aimed to protect minors, rather than the terminally ill.

The offence was created so that two specific and different kinds of ‘suicidal behaviour’ could be dealth with in different ways: providing for psychiatric treatment and closing resulting ‘loopholes’ for homicides disguised as failed ‘suicide pacts’. To expect it to function properly in debates over the rights of the terminally ill to retain dignity whilst protected against undue pressure – involving yet another type of ‘suicide’ – is unrealistic. The current Prime Minister may worry, like Macmillan, about opening himself to ‘chaff’ on suicide, but Starmer’s effort to bridge the gap between the law and the current debate requires a dangerously inconsistent ‘discretion’:

‘the position of the prosecutors has been historically that we won’t indicate in advance whether conduct is criminal or not… I do recognise that for professionals and others it can leave them feeling a little bit exposed when all they really want is some guidance.’

If the law is to work consistently, it must correspond more closely to the changing types of behaviour and debates that it is supposed to regulate. Historical understanding of the current ‘incoherence’ adds another voice to the call for change.