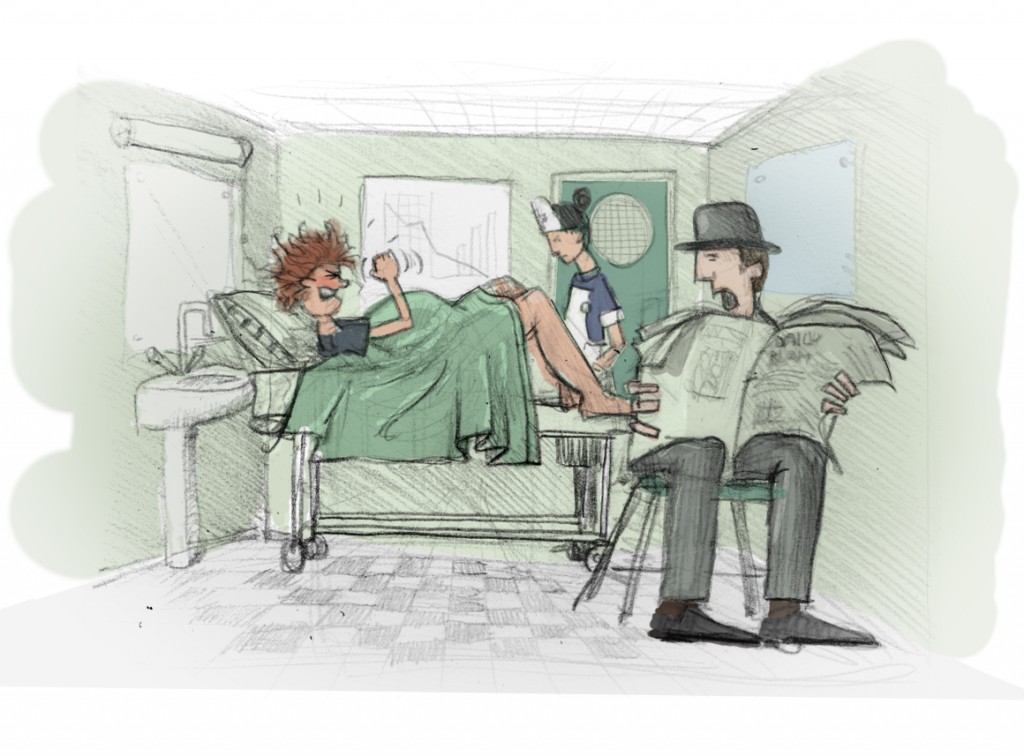

Jane Mackelworth is a PhD student at the Queen Mary Centre for the History of the Emotions. Her research examines the meaning of home, family, love and belonging for women living in romantic relationships together in the first half of the twentieth century. Here she reports for the History of Emotions Blog on the 2012 conference of the Society for the Social History of Medicine (with an original illustration by Darren Walsh).

The 2012 SSHM conference, recently hosted here at Queen Mary, took over 130 delegates on a giddy tour of some of the most cutting-edge research in the social history of medicine. Attendees were spoilt for choice with lectures and seminars touching upon topics as diverse as the implications of Wittgenstein’s theory in our understanding of pain; the chequered social history of Ritalin; men’s involvement in childbirth; and an imaginary bowler hat.

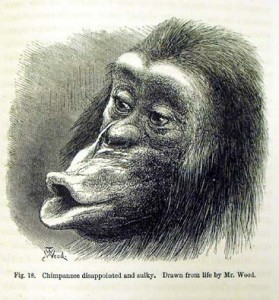

Ludwig Wittgenstein, September 1947, in Swansea Photograph by Ben Richards; © Wittgenstein Archive, Cambridge.

The conference opened with a dazzling plenary lecture from Joanna Bourke, who drew on the ideas of Wittgenstein and others to explore the nature of pain. Bourke encouraged us to think of pain as a ‘type of event’. Whilst beginning her definition of pain with the individual’s own subjective experience she quickly departed from this to emphasize the cultural and social norms that mediate our meaning and understanding of pain. She was keen to underline that this cultural mediation of pain takes place from birth. It is through language (both verbal and symbolic) that we are able to culturally make sense, not of pain itself, but of our own experience of pain. As always, Bourke was compelling and engaging and she served a strong reminder to us all to keep probing and digging at our everyday understandings of things, of feeling and of emotions.

Following the plenary delegates were offered a wide range of themed panel sessions, excellently pulled together by Professor Colin Jones, Emma Sutton and Jen Wallis. There is simply not the space to touch on all of these and so I want to highlight just one or two key themes. One prevalent theme was gender. Papers explored the ways in which definitions, diseases and ‘disorders’ became associated historically with masculinity or femininity. There were some excellent debates on the impact of feminism, and the role of post feminist theory on issues such as female sexual dysfunction. Katherine Angel in particular engaged with the thorny issue of feminism and post-feminism. She raised the challenge of how best to unpick feminist discourse without accusations of attacking or undermining the whole feminist cause. For example, is FSD purely a cultural patriarchal construct, created by doctors? Where does this leave women who may be experiencing symptoms, which cause them problems in their daily lives? Angel suggests that researchers must examine the fault-line between feminist theory and women’s own experiences, and indicated that this is what she had attempted herself in her recent Penguin book Unmastered: A Book on Desire Most Difficult to Tell.

The importance of gender in the social history of emotions and sexuality was also considered. Lesley Hall posed intriguing questions for historians of sexuality as a result of her work looking at literature in the interwar period. Most historians are familiar with the cultural images of the lesbian in sexology and also in the much quoted Radclyffe Hall’s Well of Loneliness. In these, the lesbian woman is depicted as unfeminine, as mannish. She is seen as having an inverted gender. Yet Hall demonstrates that in interwar British literature close friendships with other women became seen as dangerous or troubling when marked by an excess of emotion, which was seen as a feminine trait. Relationships were marked with a jealous intensity. This hyper-femininity is particularly interesting, as it challenges the familiar cultural depiction of ‘female inverts’ as excessively masculine. I found this particularly interesting in terms of my own research (on love, desire and ideas of home between women in Britain from 1900-1960).

The importance of gender in the social history of emotions and sexuality was also considered. Lesley Hall posed intriguing questions for historians of sexuality as a result of her work looking at literature in the interwar period. Most historians are familiar with the cultural images of the lesbian in sexology and also in the much quoted Radclyffe Hall’s Well of Loneliness. In these, the lesbian woman is depicted as unfeminine, as mannish. She is seen as having an inverted gender. Yet Hall demonstrates that in interwar British literature close friendships with other women became seen as dangerous or troubling when marked by an excess of emotion, which was seen as a feminine trait. Relationships were marked with a jealous intensity. This hyper-femininity is particularly interesting, as it challenges the familiar cultural depiction of ‘female inverts’ as excessively masculine. I found this particularly interesting in terms of my own research (on love, desire and ideas of home between women in Britain from 1900-1960).

Other scholars explored ways in which men and masculinity, have featured in medical discourse. One theme which emerged was the importance of interrogating historical statistics. For example, women have long been recognized as outnumbering men in being diagnosed with depression and many other mood based disorders. Yet Alison Haggett problematizes this in her compelling research. For example, her extensive oral history study of retired doctors reveals that men’s problems often only came to light when reported by female members of the family. Similarly men often show higher levels of alcohol abuse and this can be considered a way of ‘self-medicating’ for troubling emotions. Haggett’s work, in particular helps highlight the important role that historians can play in effecting change. Her research has a social purpose. She reminds us that, in fact, it is young men who feature highly in suicide statistics. To this end she is involved in policy- making panels to help promote understanding of the complicated relationship between men and what we think of as depression.

The role of men and emotions was also explored by Jade Shepherd in her work looking at the link between jealousy, insanity and crime at Broadmoor prison in the nineteenth century. She shows how, as the nineteenth century progressed, lawyers became less sympathetic to the notion of provocation in cases of murder or sexual assault. As this happened the defence of feelings of jealous passion leading to insanity became invoked much more frequently. This theme was also discussed by Adrian Howe who discussed how in the current day ‘diminished responsibility’ is still used as a defence by men who have murdered their partners. This lead to a discussion of the troubling split, still there in popular culture, which posits reason and emotion at opposite poles.

Yet, in addition to serious debate, there was also room for laughter. Laura King at Warwick is looking at the increasing role of men in childbirth across the twentieth century through oral histories of midwives. She shared an anecdote of the man who sat with his head behind a newspaper throughout his wife’s labour, popping his head up only once to tell his beloved wife ‘not to grunt now’ as she was about to deliver. The midwife said that this image has stayed with her throughout her career with the chap even gaining an imagined bowler hat (which sadly he was not actually wearing at the time).

Overall the conference encouraged delegates to reconsider elements of their own work. For example, the second plenary by William Reddy (for a taster, see his recent post on this blog) gave Liz Gray, postgraduate student at Queen Mary, food for thought. In his wonderful overview of the latest neurophysiological research on emotions he highlighted the way in which our own facial muscles physically respond to another person’s emotional expression and how without these movements we find understanding their emotions more difficult. This leads Liz to wonder how this would work in a comparative psychology setting, looking both at animal and human physiology. Does the same apply when observing animals (such as Darwin’s disappointed and sulky chimpanzee, pictured below)?

The final plenary session at the conference was a debate on the various ways in which historians could intervene in current debate and also show their impact. We left the lecture hall with the words of Mark Jackson ringing in our ears. He told historians to ‘be bold, polemical and unsettling’ within debates in medicine and health.

Along with the lectures and seminars the conference offered museum visits, a programme excellently put together by Liz Gray. I took part in a tour of the Doniach Gallery. The Gallery is a tiny room in the Royal London Hospital and it holds the skeleton of Joseph Merrick, known in popular culture as the elephant man. The visit prompts inevitable reflections of the role of museums and objects and questions of how best to show such ‘objects’, which were once subjects, without objectifying. The staff are passionate in their quest to ensure that Merrick receives the dignity in death which appeared to elude him during his short life. They are selective in who they allow in to the gallery and turn away visitors who they think may have dubious motives. A poem is included from Merrick’s point of view, although no one knows the origin of the poem or when it was written. However, its authenticity is not important, rather it serves as a reminder to see Merrick as subject, not object, something which all of us working in the social history of medicine would want to do.