Dr Stephanie Downes is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Melbourne, where she is part of the ARC Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions. Here she reviews Ben Lerner’s novel Leaving the Atocha Station for the History of Emotions Blog.

Dr Stephanie Downes is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Melbourne, where she is part of the ARC Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions. Here she reviews Ben Lerner’s novel Leaving the Atocha Station for the History of Emotions Blog.

Things started coming together for me while I was reading Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station: it contains multitudes. I can’t remember where I first heard about the book, but it’s just come out in paperback in Australian bookshops, and with endorsements by Jonathan Franzen, Paul Auster, and having been awarded last year’s Believer Book Award, it seemed a reasonable enough airport purchase on my way to Perth from Melbourne for an ARC Centre collaboratory on Language and Emotion. J. K. Rowling spoke recently about various moving vehicles – trains, planes – as the genesis for her literary creativity. What about reading on public transport?

There’s a passage in Lerner’s novel on reading translations of Tolstoy on a train leaving the Atocha station, in which grammar and motion merge: travel, translation, poetry, and emotion all merge in this book. One of its most fundamental questions is how poetry can or can’t represent public, as opposed to private, emotion. Adam Gordon is an American poet who has taken up a fellowship in Madrid with the supposed intention, which he pursues meanderingly, of exploring literary responses to the Spanish Civil War. It’s 2004, and by the end of the novel it’s clear that it is the Madrid train bombings at Atocha that are really at stake. The Leaving of the novel’s title is as much about the leaves of a book or a poem as about displacement. I read ‘leaving’ as describing the act of literary creation: what can an individual poet convey on the page of public tragedy? In the gently comic pretentious spirit of the novel itself, I hope the pun I’m suggesting here makes more sense of the reference to Whitman’s Leaves of Grass at the beginning of this post.

Visual art and literary expression are often synonymous is Lerner’s novel. Looking back up at the image of the cover I’ve just pasted into the text, I suddenly notice how the fragments of Renaissance painting on the right have been smeared makes them look like they’re in motion, but also has the effect of a pile of pages or sacked books: more leaves.

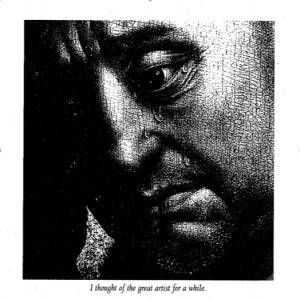

Of all the emotional multitudes in the novel, what I want to isolate is a phrase that appears in italics right at the start, and which brings me back to reading or experiencing art or literature – on trains, planes, or anywhere else. The narrator moves through the rooms of the Prado, en route, as is his habit, to position himself in front of a particular painting, Roger Van der Weyden’s Descent from the Cross. The fifteenth-century oak panel shows Christ’s lifeless body borne down amid a small crowd. Mary faints, her body in sympathy with her dead son’s, and two other figures are shown actively weeping: individual tears stand out on their cheeks. When the narrator reaches the painting, he finds an unknown man has beaten him there, and is standing in front of the work, himself weeping ‘convulsively.’ (It’s a year of literary tears for me; see an earlier review of Peter Carey’s Chemistry of Tears in this blog.) At this point the narrator asks: ‘Was he, I wondered, just facing the wall to hide his face as he dealt with whatever grief he’d brought into the museum? Or was he having a profound experience of art?’ (8)

The passage is accompanied by a black and white close-up of the face of the man on the right of Weyden’s painting. Suddenly, we’re reading faces, reading art, as well as text. The image, incidentally, is remarkably reminiscent of the close-up of Bouts’ Mater Dolorosa (c. 1460), which appears on the cover of James Elkins’ Pictures and Tears: A History of People who have Cried in Front of Paintings (Routledge, 2001). All this has made me think more about responses to, rather than representations, of emotion in literature. If we cry in front of a painting, or while reading a book, do those tears still convey ‘real’ emotion? Does emotion have to be lived to be experienced? Hamlet-like: ‘What is Hecuba to him, or he to Hecuba,/ That he should weep for her?’ (2.2.448)

The passage is accompanied by a black and white close-up of the face of the man on the right of Weyden’s painting. Suddenly, we’re reading faces, reading art, as well as text. The image, incidentally, is remarkably reminiscent of the close-up of Bouts’ Mater Dolorosa (c. 1460), which appears on the cover of James Elkins’ Pictures and Tears: A History of People who have Cried in Front of Paintings (Routledge, 2001). All this has made me think more about responses to, rather than representations, of emotion in literature. If we cry in front of a painting, or while reading a book, do those tears still convey ‘real’ emotion? Does emotion have to be lived to be experienced? Hamlet-like: ‘What is Hecuba to him, or he to Hecuba,/ That he should weep for her?’ (2.2.448)

While Lerner’s narrator looks at the weeping stranger, and we look at Van der Weyden’s weeping man, he wonders: ‘Maybe this man is an artist, I thought; what if he doesn’t feel the transports he performs’ (10).

While Lerner’s narrator looks at the weeping stranger, and we look at Van der Weyden’s weeping man, he wonders: ‘Maybe this man is an artist, I thought; what if he doesn’t feel the transports he performs’ (10).

‘Transports’ – not ‘performs’ – is the key word for me here. Emotional states are always in flux, or in motion; always changing, moving. It’s the reader or viewer that’s ‘transported,’ emotionally, or otherwise.

No wonder books and planes go together so well.

Pingback: Now We Are Two | The History of Emotions Blog