From Dec 5-7, 2012, Stephanie Downes and Stephanie Trigg convened ‘Faces of Emotion: Medieval to Postmodern,’ an interdisciplinary symposium at the University of Melbourne. Here they reflect on three days of intensive discussion on, artwork about, and performance of, facial expressions of feeling.

Researching emotions on the human face can take us into some strange and wonderful places, from Chaucer’s poetry to the ethics of cosmetic surgery.

Many academic disciplines and artistic and cultural practices are fascinated by the face and its capacity to express — and to withhold — emotion. Questions of performance, historical change and cultural difference further complicate the relationship between emotions and the face.

The Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions (CHE) focuses on the period 1100-1800. One of its research programs, Shaping the Modern, moves beyond this historical period to explore some of the ways in which contemporary Australian culture responds to the European past. The Faces of Emotion symposium brought together researchers on medieval and early modern literature and art with artistic practitioners and scholars from a range of other fields: psychologists, philosophers, photographers, museum curators and cultural theorists.

The keynote public lecture was given by Stephen Jaeger, author of Enchantment (U Penn Press, 2012), on the ‘silent’ film, The Artist. Stephen began with the story behind the cover of his book, a portrait of Durer pixilated with portraits of other faces, painted and photographed, all of which are analysed in his book. Images of these faces were pinned on the noticeboard where he worked.

His lecture drew on the long history of redemptive female faces that sits behind the 2011 film, from Dante’s Beatrice to Marlene Dietrich. In a first for CHE, the lecture was signed by AUSLAN (Australian Sign Language) interpreters. Audience members were particularly struck by the eloquent language of the hands describing Dante’s descent into hell and his ascent to the vision of Beatrice in Paradise.

It became clear over the course of the three days that the face is radically undertheorised. The scholar mentioned most often was Emmanuel Levinas, though Eileen Joy cautioned us against taking his idea of ‘the face’ too literally [see Eileen’s take on the Melbourne collaboratory in the comments thread at In the Medieval Middle]. Her paper typically ranged widely across Levinas, other metaphors of the face, Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line and Malory’s Tale of Balin. As she talked about the two Balins and the destruction of the face in this traumatic medieval battle, we looked into a still shot of the wide-eyed face of Jim Caviziel as Private Witt ‘receiving the world’ of war:

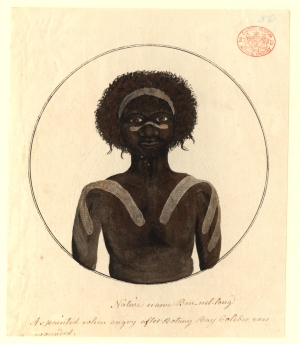

In her own paper, Stephanie Trigg explored Geoffrey Chaucer’s translations of facial expression into words, through his use of the phrase, ‘as if to say’. Many other papers also tackled the problem of the relation between image and text, and the ways textual, visual and cinematic media describe and represent faces. Joanna Gilmour, for example, a curator at the National Portrait Gallery of Australia, in Canberra, showed a portrait of eighteenth-century Indigenous Australian Bennelong. An anonymous contemporary annotation describes the portrait as painted ‘when he was angry.’

There was much discussion about the status of such descriptions, and the difficulties of attributing emotions through such highly mediated forms as portraiture and photography, especially in colonial contexts. Such descriptions openly challenge modern European understandings of the ‘universality’ of facial emotions.

A paper by Anne Maxwell on race, colonialism and photography in nineteenth-century America similarly troubled modern interpretive practices and assumptions. Are droplets of water on the skin of the face necessarily tears, or might they be beads of sweat, from heat or the exhaustion of sitting still for the camera? Reaching further back in history and across a range of cultural encounters, Jonathan Lamb, from Vanderbilt, compared Hogarth’s anatomy of the blush with the inverse patterns of facial tattoos in the Pacific.

Dianne Jones talked about her own artistic practice as an Indigenous photographer making ‘the Mona Lisa series’: portraits of her relatives posed as Leonardo’s iconic sitter. Her stunning ‘Kristy’ was the artwork adorning posters publicising the Faces collaboratory.

Odette Kelada offered an analytical approach to emotions in modern Australian art, drawing on Sara Ahmed’s Cultural Politics of Emotion (2004).

The Centre has a strong interest in contemporary Australian art and culture. A performance of a short play by Mark Nicholls (Cinema Studies at the University of Melbourne), ‘Richard II and the Old Queen,’ brought lines from Shakespeare to the fore, as we watched an actress (Madeleine Swan) playing an ageing Elizabeth as she applied heavy white face makeup to complete her onstage transformation into Gloriana:

Was this the face that faced so many follies,

And was at last out-faced by Bolingbroke?

A brittle glory shineth in this face:

[…]

Mark, silent king, the moral of this sport,

How soon my sorrow hath destroy’d my face.

[Richard II, 4.I.285-91]

We moved next from the intimacy of encounters between actors and audiences in the space of the theatre, to the modern art gallery, where a pop-up exhibition at the Brain Centre brought us face-to-face with a series of artistic expressions of emotion, using the face as a central medium. The exhibition showcased self-portraits by psychiatric patients from the Dax collection: a moving reminder of the complex interior states that can lie behind the representations of facial emotion and the therapeutic role that representation of facial emotion can play.

From a different psychological perspective, Ottmar Lipp (Psychology, University of Queensland) presented a series of ‘happy’ and ‘angry’ faces of different genders and races. These images had been shown to participants in cross-cultural clinical trials to test the speed with which emotions such as ‘happiness’ and ‘anger’ are recognised on the faces of strangers. (As it turns out, happiness wins, which puts a nice, positive spin on our assumptions with which we go into a new social interaction!)

For the historians among us, this research invited the question: how would modern participants in clinical trials interpret emotion on the faces of the past? [Editor’s note: you can read about a very unscientific and preliminary attempt at such an experiment via a previous post on this blog which includes a link to my report on using historical images in a programme teaching emotional literacy in a local school.]

The director of CHE, Philippa Maddern, wondered about the outcomes of a trial in which subjects were asked to assess images of historical faces. Her own paper suggested that medieval people looked for a range of signs in their ‘reading’ of the human face, from gesture and expression, to facial shape (shades of phrenology here?), changes in colour and complexion, and emanations such as tears, sweat, and blood.

The collaboratory showed that the face is not only interesting historically, but has political implications, especially in twenty-first century Australian contexts, from debates about refugees, indigenous relations, and the performance of gender. Interpreting and understanding emotion on the face is not just a matter of discriminating between anger and shame, for example, but about discrimination itself: faces tell emotional narratives about ethnicity and identity as well as individual feelings.

Discussions between historians and psychologists, and between theorists of visual and textual representation, confirmed just how much work remains to be done, exploring the expression and communication of emotions on the face, whether historically, or contextually. It is clear that we need longer, transhistorical as well as multidisciplinary accounts of thematic topics like ‘the face’ in the history of emotions.

Over the course of the three days, it also became apparent just how pervasive metaphorical language about the face is. This is as true of modern Australian English as it is of Middle English, Welsh [Stephen Knight on Culhwch and Olwen], and Old French [Stephanie Downes on ‘bonne chère’]. Yet while literary and artistic representations about the face seem to have much in common, historically and in the present, real faces seemed to stay elusive, somehow veiled and inscrutable.

One of the last presentations, by Meredith Jones, treated the manipulation of facial expression into individual expression in faces that have undergone cosmetic surgery. Is this the face of emotion of the future? We barely touched on issues of posthumanism and technology in the time we had for the symposium, but this might be where literary and artistic representations of the emotive face – the face as text and the face as image – finally meet with reality.

Dr Stephanie Downes is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the ARC Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions at the University of Melbourne.

Professor Stephanie Trigg is a Chief Investigator with the Centre, and leads the Shaping the Modern program. They are both members of the School of Culture and Communication at the University of Melbourne.

Pingback: Now We Are Two | The History of Emotions Blog

Pingback: Love, Pain, Ecstasy, and Murder: Christmas at the History of Emotions Blog | The History of Emotions Blog