Susanne Stoddart is a PhD student at Royal Holloway, University of London. Her doctoral research explores the role of emotion in political culture, within the context of the Liberal welfare reforms introduced in Britain during the Edwardian period.

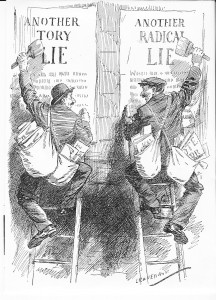

The strong link between popular politics and emotion was firmly established in Edwardian Britain: a golden age of the political propaganda poster. Contemporaries deplored the sensationalist and slanderous nature of Liberal and Conservative posters, which, they claimed, appealed with great electoral success to the uncontrollable passions and prejudices of the mass electorate. Graham Wallas, arguably the founding father of modern political psychology, referred to the ‘irrational political decisions’ that this style of popular politics resulted in. Economist J.A. Hobson asserted that the mass electorate was incapable of a ‘sustained, energetic, and well-directed effort to realise Democracy’ on account of the ‘artful appeal’ to unreason provided by popular politics.

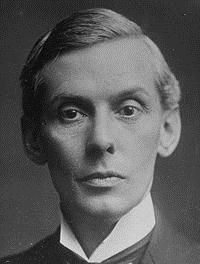

Within this context, a poster issued during a January 1910 election campaign by Claude Hay, the Conservative MP for the Hoxton division of Shoreditch in the East End of London, does not seem out of place. At this election, Hay was defending his seat against strong opposition from the recently appointed Liberal candidate for Hoxton, Dr. Christopher Addison. The future Minister of Health had previously, in his illustrious medical career, forged a reputation as one of the most esteemed anatomists of the day. Part of Hay’s poster read:

_________________________

Dr. ADDISON

ASKS FOR SUPPORT

ON THE GROUND THAT HE IS

Used to Cutting Up Bodies.

_________________________

DON’T VOTE FOR ADDISON

Who Cuts Up the Stomach

BUT

Vote for HAY

Who will see that it is FILLED.

___________________________

Hay’s poster aimed to create fear and suspicion in the Hoxton electorate about Addison’s character. Sir Victor Horsley – a renowned surgeon and a future Liberal candidate – was quick to deplore Hay’s ‘weapon of cheap abuse’, which appealed to ‘brutal ignorance’ and ‘savage superstition’ about the important work of the anatomist, implying that it was carried out ‘for the gratification of some idle curiosity’. Certainly, Hay’s attack was designed to inflame the apparent disquiet about the trustworthiness of the medical expert in Britain at the turn of the twentieth century. In her late-Victorian exploration of the urban Rich and Poor, social theorist Helen Bosanquet provided a pertinent example of such suspicion. Bosanquet uncovered concern amongst the London poor that hospitals were practising experimental surgery on patients.

Also, it could be suggested that Hay’s poster aimed to make the Hoxton electorate consider Addison’s emotional composition. As the historian Ruth Richardson has shown, from the eighteenth century it was acknowledged that the act of dissection instilled in anatomists a ‘necessary inhumanity’. Therefore, by emphasising that Addison was ‘Used to Cutting Up Bodies’, Hay wanted to remind the electorate that Addison was a man very capable of discarding all emotion. Addison had previously distributed a leaflet to the Hoxton electorate outlining his fine reputation and accomplishments at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, which served the people of Hoxton. Hay manipulated this and argued in his poster that Addison asked for political support because he was an anatomist. Therefore, Hay aimed to link Addison’s work in anatomy inextricably with his politics, perhaps aiming to suggest that he adopted a similar mind-set for both.

The suggestion that Addison was emotionally detached had the potential to discredit him and his political agenda in Hoxton. A key feature of the Edwardian Liberal Party was its concern with the provision of welfare reform, through measures such as Old Age Pensions, established in 1908, and National Insurance, passed in 1911. The reforms, which Addison fervently supported, offered hope that poverty would be alleviated for the hard working poor, or for the previously industrious elderly poor, without them suffering the shame or loss of independence associated with provisions under the Poor Law. Therefore, the legitimacy and success of welfare politicians rested to some extent on their ability to empathise publicly with the plight and emotional concerns of the poor and to develop strong social bonds. Hay’s poster suggested that it was in fact he, rather than the anatomist, who had the humanity to address the emotionally-charged issue of welfare reform, pledging that he would ensure that stomachs were filled.

Perhaps the most significant aspect of this case study for the historian of emotion becomes apparent when we move beyond considering the feelings that Hay’s poster attempted to evoke and instead uncover some of the actual emotional responses from the Hoxton electorate. While contemporaries theorised about the influence of sensationalist political posters on the supposed mass mind, the vulgarity of Hay’s poster was widely believed to have in fact lost him a significant number of votes, resulting in the election of Addison as the MP for Hoxton at the end of January 1910. The rational but emotional response to the Conservative poster by members of Hoxton’s working-class electorate can be traced through letters written to Addison following the distribution of the poster. The chief emotions expressed were gratitude towards the skill and kindness of medical men, and resentment at the offence caused to them. In one letter to Addison, published by the Liberal press, a Hoxton voter wrote:

Will you allow me, as a working man, to express my disgust at the disgraceful attack made upon you and your profession, without which so many (myself included) would now be going about limbless. It has done more for your success than all your speakers.

This extract indicates that at least some working men could look beyond the sensational appeals of political propaganda and remain mindful of social bonds and notions of mutual care. The voter was concerned not only with his own treatment by the medical profession but also with the treatment of others. Having been successfully treated by doctors and surgeons in the past, who relied upon the learning of anatomists, many of Hoxton’s working men acknowledged the role of the anatomist in securing their independence, sparing them the shame often felt by men unable to work, and to provide for their families, due to physical disability.

This brief case study illustrates that Edwardian popular politics is not only of interest to the historian of emotion in terms of exploring debates surrounding the supposed irrationality of the political process. It is certainly fascinating to deconstruct the sensationalist posters produced during this period, particularly when they provide insight into wider culture – in this case, the abuse that could still be directed at some medical experts (and not just the pro-vivisectionists). However, this case study shows that where possible the historian of emotion should look beyond contemporary theories on how the mass electorate responded to political propaganda in order to uncover the actual, conscious emotional responses provided by members of the mass electorate. This, in turn, provides a valuable lens through which we can reflect on other related themes such as issues surrounding masculinity and the working man.